I’m Not Judi Dench. So Why the Hell Would I Forgive?

By Aine Greaney

Once, on an expatriate trip back to my native Ireland, I took my mug of tea to the big kitchen window of our family home. My late-mother came to stand at my elbow. As I stood staring at our village street, Mam updated me on each neighborhood move and change: Richard, the one in the new bungalow, an old schoolmate of mine, just had another child. Mrs. H., in the sherbet pink cottage, was gone very bad with the arthritis. Mrs. L*., in the terracotta-colored two-story, the retired village school teacher, had suffered her second stroke.

Mam added: “And I heard she’s completely seafóid (in dementia) now.”

Standing there, I felt the thwack of Mrs. L’s hand across my own face. I heard that screechy voice and the classroom insults that once, when I was five and six and seven, punctuated each slap.

Slob. Thwack. Chatterbox. Thwack. Dirty. Thwack-thwack.

“Good,” I said, turning from the kitchen window.

“Good, what?”

“Good that she had two strokes and is gone seafóid. In her dotage, I hope she sees all of our little faces, all of us kids she tortured.”

Mam got that stricken look that said: So this is what America has done to my daughter.

My mother’s name was Philomena, a girl’s name that’s been démodé for years now—until the current Oscar-nominated movie of the same title. Philomena, played by Judi Dench, is a retired British nurse who travels to America to find the adult son who, as a teenager, she was once forced to give up for adoption.

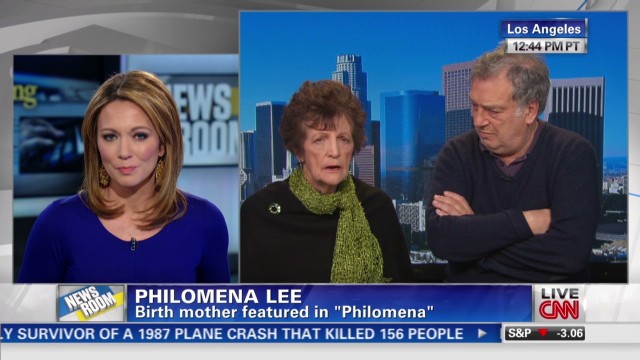

The movie borrows from a true story of the real-life Philomena Lee, an Irish expatriate in the U.K. The real Philomena was one of the Irish girls who got sent to a convent-operated mother-and-baby home and whose child got adopted out to America (for a generous donation). Philomena’s toddler son was just one of an estimated 2,200 Irish babies who got exported—often with a false birth certificate name–to U.S. Catholic families.

In the movie, new-Mom Philomena is conscripted into the convent’s unpaid labor pool—the team of fallen angels who must work off the cost of their baby’s delivery and atone for their sinful  fornication.

fornication.

By movie’s end, Philomena never meets her adult son. Her transatlantic search lands her right back in that Irish convent, where she discovers that, all along, the nuns actually knew her son’s whereabouts but, amid this and her previous mother-searches, they chose not to tell her.

Just before the credits roll, Philomena/Dench faces an aged, fire-and-brimstone Sister of Mercy, the convent’s liar-in-chief.

“I forgive you,” Philomena/Dench tells the old nun (cue the violins).

Bully for you, Philomena. I’m not as big a woman. And let me say that I don’t claim that deleting someone’s parentage and country is the same as a few grade-school beatings. Just like the movie nuns, I would bet my American house that my old teacher did not regret beating us. I would bet that she believed she was acting in accordance with her pedagogical calling. I mean, someone had to keep us tatty farm kids in line, and someone had to teach us our multiplication tables.

In the movie version of Philomena Lee’s story, the backdrop of the Gothic looking convent, the close-up of the wimpled nun and aging, kindly faced Dench create a visual auto-link between forgiveness and formal religion.

Real-life forgiveness is more nuanced and more difficult. According to one interview, the real-life Philomena Lee did, in fact, forgive those women who exported and then hid information about her child. Though a lifelong practicing Catholic, Ms. Lee’s forgiveness came not from her religious belief, but from her career as a mental health professional and the insight it gave her into the pathology of non-forgivenness.

As for me and Mrs. L., my forgiveness stalls on two major points.

As for me and Mrs. L., my forgiveness stalls on two major points.

First, some of the children in my mixed-grade classroom had learning disabilities. Also, a boy named Sean and a girl named Mary were what we now call developmentally disabled. In a more urban area, these children would have been in specialized programs, in the care of qualified and (we hope) humane professionals. But in our 1970s classroom, they got taught the eight-times tables, and slapped when they couldn’t recite them. I vividly recall Mary, who had Down Syndrome, getting beaten until she fell to the ground.

Our country villages didn’t have nuns or Christian Brothers. So these secular lay teachers, who had spouses and children and a shiny car, could claim no religious vocation as instigator or alibi for beating the most vulnerable, the most disenfranchised among us.

Here’s my second forgiveness blind spot: Without the religious vocation, without the big “C” word (Catholicism) as alibi, what could incite someone to beat someone else’s child? Enter: The other big “C” word, the one that, in Ireland or America, we still flinch at discussing: Class, as in, social class.

A decade’s worth of national investigations has uncovered part of Ireland’s shameful history of physical and sexual child abuse. Google these governmental reports and the follow-on commentary and what do you find? A digital photo of a rosary beads and a list of abusers with “Sister,” “Brother” or “Father” before their Christian names. When we read through these gut-wrenching cases, when we look beyond the Google photos or Hollywood’s facile representations, we see a recurring pattern. Most of the child and teen victims came from rural or working class families; many came from families fractured or gutted by parental death or mental illness or paternal abandonment. Some children were sent to religiously-run residential facilities for few or no other reason—no pregnancy or truancy or orphan-hood—than their family’s poverty.

By contrast, the religious charged with teaching, disciplining and housing these youngsters often came from families who owned businesses or large, prosperous farms. Some did not. But these latter had the advantage of academic scholarship or family-funded secondary education. Having a nun or priest in the family elevated the family’s overall status, and religious vocations were not an open-admissions process. So we must ask: can we truthfully separate class from religious avocation?

We must also ask: What about those secular teachers who abused without the rosary beads?

Again, let’s look at Ireland’s rigid class system. Secondary (high school) education only became free and available to all families in 1967. So for us pre- and post-European Union kids, we knew that those spelling tests and multiplication tables were our ticket up and out. Our lay teachers – smug and set in their middle-class status – knew it, too. They also knew that we came from households, from parents who lacked the public standing to object, to respectfully knock on the classroom door to say: “If you beat my child again, I will report and report and report you until I find some authority, somewhere, that will make you stop or resign.”

Just as abuse doesn’t exclusively belong within the convent walls, neither does it automatically happen across the class lines. But in the 21st century, on both sides of the Atlantic, we must first admit and then address the fact that we have entire countries and regions and cities and neighborhoods whose history, public policies and inter generational biases have spawned a set of power differentials that make inter-class abuse that much easier.

In rural Ireland, this power deficit turned some teachers into sadists and made us kids take it (literally) on the chin.

Ask any abused child or adult: there is no deleting those beatings. There is no separating that thwack-thwack-thwack from our sense of self and who we have become.

Forgive? It’s a lovely movie ending. But I’m not Judi Dench.

_____________________________________________________

Aine Greaney is an expatriate Irish writer now living on Boston’s North Shore. In addition to her four books, she has placed essays in publication such as “Forbes Women,” “The Daily Muse,” “Salon.com,” “Boston Globe Magazine” and “Books by Women.” Her essays have been cited as a “Best American Essay 2013” and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. In addition to writing, she creates and leads workshops for colleges, arts organizations and schools.

Aine Greaney is an expatriate Irish writer now living on Boston’s North Shore. In addition to her four books, she has placed essays in publication such as “Forbes Women,” “The Daily Muse,” “Salon.com,” “Boston Globe Magazine” and “Books by Women.” Her essays have been cited as a “Best American Essay 2013” and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. In addition to writing, she creates and leads workshops for colleges, arts organizations and schools.

20 Comments