No More Disposable Love: Expanding the Bechdel Test for Movies

By Guest Contributor on April 23, 2014By Lily July

Imagine a TV world where being rejected by a woman meant sending her a respectful “Sorry it didn’t work out” note and leaving her alone.

“I love women!” declared an enthusiastic Jack Nickolson in his defense. In 2000, he was accused of inviting two prostitutes to his house, not paying them, and then pushing one down then stairs resulting in brain damage. I do not doubt that Nickolson loves women. But in our culture, is that much of a defense? What does “love” mean?

I worry that our culture teaches men to “love” women the way a hunter loves deer: as something to be admired for its grace, to be loved for how it makes the hunter feel, and ultimately to be consumed and destroyed. Too often, we are not taught to love others for their own intrinsic worth and self-direction.

For instance, a recent fast food commercial featured a man who loved burgers so much that he married one, complete with a veil, and a walk down the aisle. This advertisement ends with the unfortunate phrase, “You may eat the bride” as the man proceeds to literally bite into, enjoy, and destroy his purported object of love. This is a reminder of role that consumers play– to use up and destroy what they desire, so that more can be made and sold.

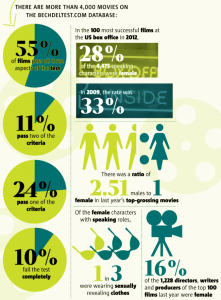

Movies, music, television, and online shows all influence how we treat each other. In 1985, LGBT writer and comic Alison Bechdel challenged Hollywood with what became known as The  Bechdel Test. A character in her comic “Dykes to Watch Out For” presents her Rule: she watches only movies in which 1) there are at least two women, and 2) they talk to each other 3) about something other than a man. The test was never meant as a way to ensure that a movie was feminist, but rather it pointed out that in so many movies, women are presented merely as love interests for men, and not as protagonists in their own right. This test is a challenge to the heterosexual focus of Hollywood movies, as well as a challenge to create worlds where women are as important as men, where women are not just bit characters and romantic interests of men, but can act and interact in the world in their own right. That the majority of Hollywood movies fail the test is disheartening, since the bar is set relatively low, but it is also a call to action.

Bechdel Test. A character in her comic “Dykes to Watch Out For” presents her Rule: she watches only movies in which 1) there are at least two women, and 2) they talk to each other 3) about something other than a man. The test was never meant as a way to ensure that a movie was feminist, but rather it pointed out that in so many movies, women are presented merely as love interests for men, and not as protagonists in their own right. This test is a challenge to the heterosexual focus of Hollywood movies, as well as a challenge to create worlds where women are as important as men, where women are not just bit characters and romantic interests of men, but can act and interact in the world in their own right. That the majority of Hollywood movies fail the test is disheartening, since the bar is set relatively low, but it is also a call to action.

Disney took the criticism to heart when creating Frozen. Responding to the Bechdel test, co-director Jennifer Lee says, “Got that. We definitely pass.” [1] [2] Marketed to both boys and girls, Frozen has brought in over $1 billion in revenue. Much of the plot centers around the relationship between the sisters as they grow up, and their struggle with obligation and personal freedom. The sisters talk to each other about plenty of things that have nothing to do with men or love interests (although they do talk about that, as well). Although men have replaced several of the female characters from the original, Snow Queen, ,the role of the Sámi people is improved upon. Main character Kristoff is a member of the indigenous Scandinavian people Sámi, wearing traditional Sámi clothing and engaging in traditional reindeer herding (though with Disney’s anthropomorphizing twist). [1] [2]

Disney took the criticism to heart when creating Frozen. Responding to the Bechdel test, co-director Jennifer Lee says, “Got that. We definitely pass.” [1] [2] Marketed to both boys and girls, Frozen has brought in over $1 billion in revenue. Much of the plot centers around the relationship between the sisters as they grow up, and their struggle with obligation and personal freedom. The sisters talk to each other about plenty of things that have nothing to do with men or love interests (although they do talk about that, as well). Although men have replaced several of the female characters from the original, Snow Queen, ,the role of the Sámi people is improved upon. Main character Kristoff is a member of the indigenous Scandinavian people Sámi, wearing traditional Sámi clothing and engaging in traditional reindeer herding (though with Disney’s anthropomorphizing twist). [1] [2]

Many have hailed Disney for creating a film where family love, not marriage, is central. The women are portrayed as powerful and complex. They make mistakes, they learn, and they grow. Yet, as many have pointed out, passing the Bechdel test does not guarantee that a movie promotes the best images of women. Sure, the women in Frozen talk to each other about things other than a man. And, admirably, the ultimate sign of love is putting your sister’s wellbeing above your own. This new Disney movie goes so far. And yet we still see a pattern so insidious that it is barely mentioned by critics: some characters treat women as disposable.

To bring this point home, I propose another test to make visible what we are teaching young people about love and desire. This Praying Mantis test poses two questions of any movie or show:

1. Does a man kiss a woman?

2. Does he later try to kill her?

Shockingly, Frozen fails this test.

Movies that fail the Praying Mantis test often do so because they connect sex with violence. This re-enforces the mistaken notion that when a man desires a woman, she becomes his property; he owns her. And once he owns her, the tragic message continues, he can decide what to ‘do’ with her and to her: to love and cherish her or to discard and destroy her. Women become consumables, to be used up and thrown away. Some might say the message is subtle, but that makes it all the more insidious. The image of a man trying to kill his former lover or fiancé has become so normalized that we don’t even remark upon it.

We see failures where we might expect them, in action movies full of misogyny and violence (James Bond, Battlestar Galactica). We see failures in classics like Othello and Oliver Twist, stories that fail the Bechdel test as well because women appear merely as supporting characters. But what is surprising is the number of PG- and G-rated, family focused, fun movies that fail the Praying Mantis test. These “fun” movies include The Princess Bride, Indiana Jones, and Frozen.

Some might defend James Bond saying, “But she was trying to kill him!” Reality check: do men or women initiate most homicides? In movies, we often see women seducing men in order to distract and kill them, when in real life it is overwhelmingly men who use violence against women. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, 70% of people killed by their lovers in the U.S. are women, presumably most of whom are in heterosexual relationships. The misleading trope of the sexy vixen is part of the damaging message about love. It mistakenly teaches men that  sexually secure women are dangerous, and it is okay to harm the person you desire (it is even required!).

sexually secure women are dangerous, and it is okay to harm the person you desire (it is even required!).

Others might point out that, for instance in Frozen, “He was the bad guy, he is supposed to do evil things.” Bad guys are powerful. Viewers try to emulate power, both consciously and unconsciously. If we show movie villains swearing, our kids at home will want to swear. If we show movie villains treating lovers poorly, our kids will want to treat their lovers poorly. Let’s stop giving our kids bad ideas.

The Praying Mantis test doesn’t go far enough, but it is a start. Cases of outright sexual assault also need to be discussed and addressed by our society, but in a way that is not voyeuristic. Assault is not entertainment, despite being rampantly depicted as unproblematic in our movies and television shows (Downton Abby and Girls, for example). Some new tactics in television have been successful at addressing sexual assault, rather than reveling in it. House of Cards, the Netflix drama about corruption in D.C., fails the Praying Mantis test miserably. Nonetheless, it succeeds in this regard: sexual assault is portrayed as a problem for the assailant, who is held accountable for his crime.

It would be great to integrate new tactics. Let’s use the power of movies to create the world we want to live in, to show how love, desire, disappointment and respect can co-exist.

At best, love means wanting what is best for your beloved – the way parents love their children. At worst, we are taught that love means wanting something for yourself, and if you can’t have it, destroying it. With hundreds of thousands of men hurting the women they “love” we have had enough destruction. The women represented in movies are not consumables. The men who watch them are not consumables either, to be used up and thrown away by the movie industry after it gets their money. It is time to bring out the best in our boys and our men by modeling new levels of accountability, portraying a diverse range of positive characters, and cultivating “new” socially acceptable forms of masculinity. Let’s create movies where women are not disposable, where losing desire for a women does not mean she is worthless, and where being rejected by a woman does not mean hurting her – but instead means sending her a respectful “Sorry it didn’t work out” note and leaving her alone, alive and able to choose her own destiny.

____________________________________________________________________

Lily July is a mom with a Ph.D. in philosophy. She researches the ethics of parenthood, the environment, images of women and men, and science and technology in our society.

You may also like...

3 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: No More Disposable Love: Expanding the Bechdel Test for Movies | thefeministblogproject

Pingback: Tech CEO Will Serve No Jail Time For Hitting Girlfriend 117 Times | sexynewz.com