COLLEGE FEMINISMS: For Darker Sisters

By Ahmad Greene-Hayes

I am the great-great-great grandson of former enslaved Georgians—the Johnson family to be exact. I come from a lineage of individuals whom I do not know, and unfortunately know little about. All I know is that they picked cotton and tobacco, tilled fields, and did all they could to comply with Massa’s every command lest they be beaten with many stripes. They were tenacious. With wounded spirits and equally wounded flesh, they stood strong. Praying by night and singing hymns by day, they climbed Jacob’s ladder. “Steal away to Jesus” and “I need thee, oh, I need thee” were their personal favorites. Though I know little about the specifics of their movement from the plantation, once the Emancipation Proclamation was implemented in 1863 and the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in 1865, I know that my family remained in Georgia throughout Reconstruction to Jim Crow and some family members even remain there today.

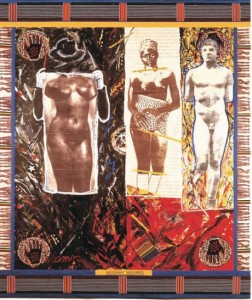

My foremothers and forefathers are what the author of Hebrews terms “a great cloud of witnesses.” I do not know them, yet they know me. Their unique struggles and their inimitable narratives have become indistinguishable under the legacy of slavery and its cruel cousin, Jim Crow. They were beaten, whipped, and lynched. The mothers, sisters, aunts, and daughters of the Johnson family were often raped, sexually abused, and “objectified as vagina” as Womanist Scholar Renee K. Harrison argues, “Once the black woman was reduced to a vagina, in the eyes of her master she was an object—a reproduction tool or a fantasy fulfillment for sexual appeasement and breeding” (73). The objectification, or the dehumanization of the black woman, was augmented by the overarching system of slavery set in place by the American patriarchs over black and brown bodies, and also over women—white women, and of course, those who comprised the racialized other. The patriarchs believed that all men were created equal and governments were instituted among Men. Black women were devoid of autonomy—their blackness made them animals fit for breeding, and their femininity made them inferiors in an overbearingly patriarchal culture.

Even still, these women, my foremothers, were strong. Strong not because they had to be, but because they just were. They bore life, often against their own will, and yet they found ways to mother. They mothered the men, they mothered each other, and they mothered their white massas, their wives, and their children. The true mothers of the plantation were unrecognized and silenced.

Black sociologist, historian, Civil Rights activist, and author W.E.B. Du Bois writes in his 1920 book Darkwater,

The world that wills to worship womankind studiously forgets its darker sisters. They seem in a sense to typify that veiled Melancholy:

“Whose saintly visage is too bright

To hit the sense of human sight,

And, therefore, to our weaker view

O’er-laid with black.”

Yet the world must heed these daughters of sorrow, from the primal black All-Mother of men down through the ghostly throng of mighty womanhood, who walked in the mysterious dawn of Asia and Africa; from Neith, the primal mother of all, whose feet rest on hell, and whose almighty hands uphold the heavens; all religion, from beauty to beast, lies on her eager breasts; her body bears the stars, while her shoulders are necklaced by dragon; from black Neith down to

“That starr’d Ethiop queen who strove

To set her beauty’s praise above

the sea-nymphs,”

through dusky Cleopatras, dark Candaces, and darker, fiercer Zinghas, to our own day and our own land, –in gentle Phillis; Harriet, the crude Moses; the sybil, Sojourner Truth; and the martyr, Louise De Mortie (97).

Black women occupy a precarious space within Anglo-white supremacist, sexist, and classist America. Their epidermal is too black, their bodies too unique and their experiences too complex.

The Johnson women, though often forgotten, were integral to the preservation of my family, our sense of self, and the attainment of black civil rights. They stood side by side with enslaved black men on the Georgia plantation grounds, side by side with the black men of Reconstruction who had received the right to vote 50 years before them, and side by side with the men of the Black Power and Civil Rights Movements, despite some black men’s demonstrated sexism, misogyny, and sexual abuse, as argued by Danielle McGuire and Assata Shakur. Black men became, and in many ways still behave, as the emulators of the white slaveholding class, which is elucidated by feminist scholar bell hooks‘ argument: “sexism militates against the acknowledgement of the interests of black women” (7).

I remember my great-grandmother as a way to interrupt these narratives. As a Johnson woman, she personified courage, inner peace, and strength. I was only four years old when she passed. I have vague memories of her, very vague, but I do remember her. For the first four years of my life, I spent almost everyday with her. I’m told that Grandma Louise would tie me into my high chair, as she sat down at the kitchen table with her Bible and a fresh pot of coffee, quoting scriptures, and meditating with silent prayer. When she was done, she would drink some coffee and then with her wrinkled, caramel-shaded thumb and finger, run droplets of the brown liquid along the edge of each page she had read, giving it a historic feel. My family always respected this custom as an outward sign of her spiritual grace. She was not only committed to her family but also to her community and her church. Grandma Louise was one of many churchwomen who filled the coffers that kept the church doors open. She cooked fried chicken dinners, baked cakes, fed the hungry, and selflessly gave of her earnings for the upkeep of the ministry. Even though black men in many ways remain(ed) the face of the black church, women like Grandma Louise fought and struggled that those spaces would exist for black upbuilding, spiritual fulfillment, and sociopolitical awareness.

I see the same spirit in Grandma Louise’s daughter, my Nana, and in her granddaughter, my Mother. These women embody the resistance and strength of their foremothers, as they have all bore their share of pain, loss, and trauma. My Nana raised three children on her own in the black ghettos of Newark and East Orange, New Jersey during the 1970s and 1980s, all while my grandfather paraded the East Coast as a rolling stone. My Mom managed to escape the domestic abuse of my biological father, when I was still in diapers, and raised me all by herself. She also resiliently navigated the racist and sexist substructures of law enforcement as a black female officer in a time when white male officers dominated and openly despised their black female counterparts.

As a black male scholar committed to studying and appreciating feminist theory, womanist theory, queer theory, and theorization as a process for applying language and succinct articulations to lived experiences, I know that the women in my family exude feminisms unique to their complex lives and histories. During Women’s History Month and every month, I pay homage to black women like Audre Lorde, bell hooks, June Jordan, and Patricia Hill Collins who have linguistically and artistically crafted ways to give intellectual meaning to experiences often denied attention. In that same spirit, I also honor the organic, non-academic narratives of black women like my nana and mama who also have claims to modern feminist discourses of race and gender.

Black women—scholars and non-scholars alike—have historically been viewed as “nasty wenches,” “jezebels,” “welfare queens,” “emasculators,” and “mammies,” and even contemporaneously seen as “hot mommas,” “bitches,” “hoes,” and the like, yet they rise. Trudier Harris argues, “the black American woman has had to admit that while nobody knew the troubles she saw, everybody, his brother and his dog, felt qualified to explain her, even to herself” (123). As the patriarchs would have it, the black woman’s racialized otherness and her femininity have debarred her from participating in an American democracy predicated on supposed freedom. Consider, for example, the starkly racialized rhetoric regarding Black Women’s Reproductive Rights. In a system maintained by the preservation of white patriarchy, white supremacy, and the sanctity of whiteness as an exclusive, socially constructed racial category, black women are relentlessly held captive, physically and psychologically denigrated, and sexually abused and exploited. Whether enslaved on the plantation, marching in solidarity with male Black Power activists, or simply existing in their own communities, black women are constantly attacked, threatened, and suppressed by white men, white women, black men, and even by other women of color. If you need further tangible evidence, take a look at how First Lady Michelle Obama was portrayed as a slave with her breast exposed in the August 2012 issue of Magazine Fuera de Serie, or critically examine the ways in which black women, their bodies, and their experiences are incessantly policed, fetishized, and scrutinized in the media, among many other avenues and spaces—the recent cases of Lupita Nyong’o, Oprah, and gospel recording artist Erica Campbell are only a few examples.

I write this piece as a black man impatiently waiting for slavery and all its transgenerational rearticulations to die. I am both frightened and appalled by the implications of slavery and neoslavery for black women, especially in the age of supposed post-racialism, post-sexism, and post-colonialism. I find myself unimpressed and frustrated with black men and white and brown women who wage war on anti-black racists without hesitation, yet falter in their allyship and advocating for and with their “darker sisters.” I write this piece for the Johnson women and for black women everywhere, who have been oppressed in the American nation-state since the 16th century Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. I write this piece in honor of Sally Hemings, Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, Mary Church Terrell, Alice Walker, Renisha McBride, Melissa Harris-Perry, Janet Mock, and for all sistas, everywhere. For truly remembering is a form of anti-sexist, anti-colonial, and anti-racist resistance. We remember to fight. We remember to celebrate. We remember to live.

With love and in solidarity.

________________________________________

Ahmad Greene-Hayes is a student at Williams College, a Jackie Robinson Scholar, a History major, and an Africana Studies concentrator. He is deeply passionate about civil rights, social justice, and activism. During the summer of 2013, Ahmad was a BNY Mellon Pre-Professional Collections Apprentice at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York. At Williams, he is student chair of the Honor and Discipline Committee and he works tirelessly as a student-activist, both within and outside of the Minority Coalition, to raise awareness about race, class, gender, and sexuality issues. He was recently accepted as a Mellon Mays fellow, in which his research will focus on African American history, Women’s history, feminist, and womanist history, Whiteness, White terrorism, and constructions of liberation ideology. He is also the co-founder of Kaleidoscopes: Diaspora Re-imagined, a student-run academic journal that offers a space for scholars and social activists to interrogate issues pertinent to the African diaspora, while concomitantly deconstructing dominant historical discourses involving people of African descent. Follow him on Twitter @_BrothaG.

Ahmad Greene-Hayes is a student at Williams College, a Jackie Robinson Scholar, a History major, and an Africana Studies concentrator. He is deeply passionate about civil rights, social justice, and activism. During the summer of 2013, Ahmad was a BNY Mellon Pre-Professional Collections Apprentice at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York. At Williams, he is student chair of the Honor and Discipline Committee and he works tirelessly as a student-activist, both within and outside of the Minority Coalition, to raise awareness about race, class, gender, and sexuality issues. He was recently accepted as a Mellon Mays fellow, in which his research will focus on African American history, Women’s history, feminist, and womanist history, Whiteness, White terrorism, and constructions of liberation ideology. He is also the co-founder of Kaleidoscopes: Diaspora Re-imagined, a student-run academic journal that offers a space for scholars and social activists to interrogate issues pertinent to the African diaspora, while concomitantly deconstructing dominant historical discourses involving people of African descent. Follow him on Twitter @_BrothaG.

0 comments