Rethinking Dear White People: One Viewer Questions its Depiction of Microagressions for Today’s Youth

By Monique John

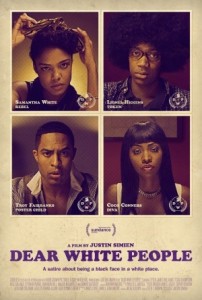

While only recently picked up by Lionsgate Films, Dear White People has had the Internet buzzing for over a year. The indie black art-house film, directed by Justin Simien, has captured the public’s imagination with its narrative and explicit racial politics. Dear White People is set at a fictitious Ivy League school, Winchester University, and chronicles the lives of four black students: Sam, a militant, outspoken radio jockey; Coco, a flashy, aspiring reality star; Troy, the handsome big man on campus and Lionel, a nerdy, budding student journalist who’s an outcast to the rest of the student population. Though they occupy different spaces in Winchester’s social scene, their lives become intertwined when a group of white classmates decide to throw an “African-American” themed party.

While only recently picked up by Lionsgate Films, Dear White People has had the Internet buzzing for over a year. The indie black art-house film, directed by Justin Simien, has captured the public’s imagination with its narrative and explicit racial politics. Dear White People is set at a fictitious Ivy League school, Winchester University, and chronicles the lives of four black students: Sam, a militant, outspoken radio jockey; Coco, a flashy, aspiring reality star; Troy, the handsome big man on campus and Lionel, a nerdy, budding student journalist who’s an outcast to the rest of the student population. Though they occupy different spaces in Winchester’s social scene, their lives become intertwined when a group of white classmates decide to throw an “African-American” themed party.

The main objective that Simien has in the film is shedding a light on the microagressions students of color face while attending predominantly white universities. But given the large cast, there are various other themes that Simien fits into the work as well. One is the inner turmoil of the mulatta. Another is black people’s desire to capitalize on their own unsavory stereotypes, given the reach, glamour and influence of reality television. A third is the longing for young blacks to be accepted (by those inside and outside of their own race) despite one’s own interests and experiences that depart from customs and products associated with black culture.

It is undeniable that Simien has accomplished a lot with this film, as he has become a master in digital marketing. His tactics have worked well, garnering his target audience of “conscious” (black) hipsters in front of the big screen so we can “start the conversation.” But despite having all the right people in the right place, the conversation Simien was trying to raise didn’t actually go anywhere, and the movie (though entertaining) simply regurgitates things we all already know to be true.

Dear White People is also a reminder of two things not-to-do when creating a film that discusses race and identity politics: one, create a cultural product that leaves people with caricatures of themselves, rather than mirrors that highlights the complexities of identity. Two, discuss race so boldly and through avenues that are so well traveled in the script that it doesn’t leave room for the audience to talk about the topic in new ways.

The beauty of Dear White People’s premise is that it puts a microscope on the very timely and disturbing trend of race-themed college parties. The movie is filled with tongue-in-cheek references to racial stereotypes. Simien’s style of addressing the phenomenon is an obvious nod to the techniques of art-house films by Melvin Van Peebles and Spike Lee from years past. For example, Troy’s mousy white girlfriend pleads him to screw her with his giant black cock. Armstrong/Parker, the dining hall of the predominantly black residence hall on campus, serves chicken and waffles in every meal scene. And of course, Coco, a pretty dark-skinned girl rants in her vlog about her white classmate’s intrusive questions about her hair-styling choices.

The beauty of Dear White People’s premise is that it puts a microscope on the very timely and disturbing trend of race-themed college parties. The movie is filled with tongue-in-cheek references to racial stereotypes. Simien’s style of addressing the phenomenon is an obvious nod to the techniques of art-house films by Melvin Van Peebles and Spike Lee from years past. For example, Troy’s mousy white girlfriend pleads him to screw her with his giant black cock. Armstrong/Parker, the dining hall of the predominantly black residence hall on campus, serves chicken and waffles in every meal scene. And of course, Coco, a pretty dark-skinned girl rants in her vlog about her white classmate’s intrusive questions about her hair-styling choices.

The film is filled with jokes and situations that compel laughter because the situations are all-too familiar, realities that you have experienced or at least heard of before. But if Simien wanted to talk about how “mass culture responds to a person because of their race,” then can we talk about why the director chose to use the tired trope of the tragic mulatta as the binding element throughout all of the narratives in this film? That’s not to say that Tessa Thompson wasn’t black enough to play the role of Sam, the wannabe nationalist, or that the narratives of bi-racial people are disposable in a film about race. Sam, a woman pretending to be more committed to black culture than she truly was, was one of the less interesting characters to watch.

There is something powerful about the less prominent narrative of Coco (Teyonah Parris), a woman who flirts with respectability politics and appears to not have any qualms about her identity that I find much more compelling. Her character is the definition of code switching—Coco dons black and blonde wigs, and often wears plunging necklines, whether wearing preppy school clothes or clingy party dresses. In an interview with a TV producer, Coco speaks the King’s English but on her vlog, “Doing Time at an Ivy League,” Coco peppers her voice with home  girl slang. She even participates in her white classmates’ racist, outlandish stunts for her own fame. Coco is a woman who works within a racist and classist system, manipulating it as a source of her agency. Like Sam, Coco is constantly performing a legible and profitable inscription of blackness. Yet, what is key to understanding Coco is knowing that her blackness is a single element in her identity, not the totality of it.

girl slang. She even participates in her white classmates’ racist, outlandish stunts for her own fame. Coco is a woman who works within a racist and classist system, manipulating it as a source of her agency. Like Sam, Coco is constantly performing a legible and profitable inscription of blackness. Yet, what is key to understanding Coco is knowing that her blackness is a single element in her identity, not the totality of it.

However, Coco is cornered off by Sam’s role as the visionary; Sam is caught between two worlds. The director relies on one of the most predictable narratives of black identity (and oppression)—the tragic mulatta—to serve as the frame for the entire story. Sam guides us throughout the film; she opens the movie as the popular, witty talking head, boldly poking at her white classmates’ awkward (if not disrespectful) interactions with students of color and appropriation of black culture. At one point, she even bans white students from entering Armstrong/Parker.

Sam guides us throughout the film; she opens the movie as the popular, witty talking head, boldly poking at her white classmates’ awkward (if not disrespectful) interactions with students of color and appropriation of black culture. At one point, she even bans white students from entering Armstrong/Parker.

Coco is often seen and heard, but her constantly seductive and calculating demeanor is overshadowed by Sam’s relationship with her dying father and her frustrations with Gabe (both men are white). We see Sam’s character shift when faced with a dilemma and must stop running from her own discomfort with her Caucasian lineage. She is at a crossroads: either she accepts her role as the leader of Winchester’s black students through condemning her white classmates’ heinous actions, or she take on her role as the doting daughter and girlfriend who devotes her attention to the (white) men that love her dearly—both of them being people that are on the brink of leaving her. Both Coco and Sam’s futures are uncertain by the end of the film. We are left with the sense that Coco is left to her own devices still chasing fame without a friend (or lover) by her side. Sam, on the other hand, is the last main character we see on screen, appearing more sheltered and content as long as she has the company of her white loved ones.

I acknowledge my bias in responding to this film as a dark-skinned woman. It is no secret that we are constantly being depicted on screen in limited and problematic ways. Frankly, I think I’m a little irritated at watching another dark-skinned woman be featured as a marginalized character within a film about marginalized people.

But the film falls short in other ways. Creating a race-themed art-house film for millennials is not as simple as recycling lines from School Daze and polishing them with references to smartphones and social media. Furthermore, there’s more to microaggressions than hair politics and fetishes for interracial sex. Incorporating race so boldly into the script is what some might argue the thing that makes the film’s portrayal of microaggressions powerful and unapologetic. However, the essence of microaggressions rests within their ubiquity not the spectacle. They often seep into our daily conversations and interactions when we’re not directly talking about race itself.

Capturing contemporary young black people’s frustration with the messiness of racial politics means depicting our vulnerability to ignorance and racist behaviors within intimate settings—whether or not we have white relatives. Strangely, Simien’s film depicts the lives of white and black students as highly segregated, but for many of us across the (black) skin-color spectrum, white people are now our friends, family, professors, mentors, co-workers, employers and employees. We all face the challenge of addressing the racial hatred that lives inside some of the people who love and support us the most.

Capturing contemporary young black people’s frustration with the messiness of racial politics means depicting our vulnerability to ignorance and racist behaviors within intimate settings—whether or not we have white relatives. Strangely, Simien’s film depicts the lives of white and black students as highly segregated, but for many of us across the (black) skin-color spectrum, white people are now our friends, family, professors, mentors, co-workers, employers and employees. We all face the challenge of addressing the racial hatred that lives inside some of the people who love and support us the most.

I already know why my non-black friends like to touch my hair and make unwarranted comments about my body. They’re curious, and aren’t always aware of the exploitative history of black women’s bodies. I already know that my white girlfriends will lust after my brothers because they want to see if the old wives’ tale is true. I know that my brothers will lust after them as well, for having me on their arms wouldn’t look nearly as fashionable. And I know that my friends and employers will say that minorities must stop using “isms” as an excuse for the achievement gap, because their privilege prevents them from seeing the intersecting oppressions they feed into, yet rarely are impacted by.

The unknown lies in what transforming our conversations (or venting) about race into action would actually look like. How do I get my white friends to understand that my outspokenness about racial conflict is not about self-pity, but about reflection? How do I call out my white friends and acquaintances for the ignorant things they say or do without making them feel they are being attacked? Should I actually care about how they take criticism on their understandings of race and identity? Is it even my responsibility to get my white friends to understand these things? Whatever the answers to these questions are, we’re doing ourselves a disservice if we let the comfort of dialogue and sensational media items distract us from mobilizing ideas on how to improve race relations and identity politics in the real world.

___________________________________________

Monique John is a writer and activist specializing in feminism, racial politics, media representation and hip hop culture. Her writing has been featured in The Root, For Harriet, The Feminist Wire and Redbook Magazine. Monique has also spoken at Fordham University, Tulane University and the Borough of Manhattan Community College for her research and writing on black sexual politics and violence against women. You can find more of Monique’s work at her personal website as well as her musings on hip hop feminism and the strip club chic at her blog, Twerked.

Monique John is a writer and activist specializing in feminism, racial politics, media representation and hip hop culture. Her writing has been featured in The Root, For Harriet, The Feminist Wire and Redbook Magazine. Monique has also spoken at Fordham University, Tulane University and the Borough of Manhattan Community College for her research and writing on black sexual politics and violence against women. You can find more of Monique’s work at her personal website as well as her musings on hip hop feminism and the strip club chic at her blog, Twerked.

Pingback: The Feminist Wire: Rethinking Dear White People | Monique John