Personal is Political: Chicana Motherwork

By Michelle Téllez

This year marks the 20th anniversary of my father’s death. The same year that the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, Mexico galvanized people from around the world with, “A world in which many worlds exist,” the world that I knew crumbled around me. I was twenty years old, and those of us who were still in the home—my mother, my sister and myself—slowly tried to reassemble our quotidian life. Our familia de mujeres grew as my sister began to have children and became the sole bearer of responsibility for her two girls.

My form of survival over the next ten years was to travel and experience the world in a way that deviated from what I had always known. But in those years, every time I returned to the home in which my mother and sister shared, I often asked myself what it was that I was doing away from them. The feeling intensified when I would wake up to hear and see my sister feeding my infant niece in the middle of the night or when I would watch my mother rise early and cook for her granddaughters every morning. Years later, the feeling deepened when my mother became terminally ill, and I witnessed my sister take most of the responsibility for her everyday care. The contradictions of accountability, belonging, and family have followed me throughout my life.

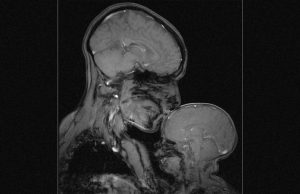

Twelve years to the date after my father died, my daughter was born, a strange coincidence for some, but a reminder to me that my coming into motherhood was directly linked to his memory and his spirit. My daughter was 5 when she lost her bia, my mother. Although my mother had retreated to the echoes of her mind since I had announced my pregnancy, her physical departure left a gaping hole in the lives of our family. As an adult child with no living parent, I’ve had to think long and hard about carework and mothering, about what it means and what it can look like in the absence of those that cared for and parented me. These musings have taken me back on long journeys through my childhood as a way to imagine how these experiences have and will shape my own daughter’s life.

Thinking about the work of Patricia Hill Collins, Adrienne Rich, Sara Ruddick, Cherríe Moraga, and Lisa Udel on “motherwork,” I ask myself what a Chicana Motherwork looks like? I wonder how does our “motherwork” not only reflect the tensions that emerged during our own identity formation in our upbringing, but also the ways in which we continue to negotiate our experiences and histories in the U.S.? In our home, my mother’s “motherwork” was rooted in familia, community, and cultura. These lessons shaped how I understand myself and my place in this world.

As Gloria Anzaldúa so aptly describes in “To Live In the Borderlands” in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mesiza, Chicanas continuously move in and out of cultural practices in ways that become normalized; we recreate and retain practices in ways that come to exemplify our “subtle acts of resistance,” which allow us to mark our place in society as Chicanas. Remembering the lessons and memories of my family—the music, the storytelling, the relationship with my family hundreds of miles away across the divide known as the U.S./Mexico border and of course the reprimands from my mother when she felt I was becoming too agringada (too Americanized)—helps me make sense of several political, social, and cultural contradictions that inform my own mothering practices. While I will introduce my daughter to Mexican cultura and ceremony, she will also learn about U.S. based artists, Sufi poetry, will dance bachata, and have Trader Joe’s-inspired chicken tikka masala and naan for dinner. Our homeland will always be directly connected to my mother’s small town in Mexico, but because of the larger Chicana community in which we are surrounded, she will also have access to the diversity that is Mexico, manifested in different music genres, foods, and ancestry. The kind of exposure to language that I give to my daughter is also very different from my own. While I only spoke to her in Spanish for the first two years of her life, we now converse primarily in English. My mother fought to remove me from ESL classes because I was bilingual, but I have fought to find a dual-immersion Spanish language program to retain my daughter’s bilingualism in a state that deems these programs illegal. Language codifies the ways we make meaning of the world, and if I am not committed to this goal, the ways my daughter hears and feels the world will be entirely different. By using cultura as a preservation tool, Chicana motherwork becomes praxis and resistance in contemporary U.S. society.

Moreover, while Chicana motherwork requires an adaptation of cultural practices, tools, and exposure, it also means reinterpreting motherhood. My mother was taught to sacrifice herself for her familia, a role she readily embraced as she gave everything to her family of origin and to the one she created. I think her commitment was admirable and that her strength was invincible. But at what cost does this selflessness come? My mother did little to care for her own emotional well-being. The reality is that in the process of giving it all to the familia, she never gave enough to herself. After my father died and we became adults, this became overwhelmingly visible. As a Chicana single mother, I refuse to believe that motherhood implies a relinquishment of self. Instead, I argue that motherhood implies the creation of a greater self that is in constant regeneration. In order to sobrevivir (survive), the labor of mothering involves constant negotiations within families and communities, fully thinking through the politics of accountability and belonging.

Moreover, while Chicana motherwork requires an adaptation of cultural practices, tools, and exposure, it also means reinterpreting motherhood. My mother was taught to sacrifice herself for her familia, a role she readily embraced as she gave everything to her family of origin and to the one she created. I think her commitment was admirable and that her strength was invincible. But at what cost does this selflessness come? My mother did little to care for her own emotional well-being. The reality is that in the process of giving it all to the familia, she never gave enough to herself. After my father died and we became adults, this became overwhelmingly visible. As a Chicana single mother, I refuse to believe that motherhood implies a relinquishment of self. Instead, I argue that motherhood implies the creation of a greater self that is in constant regeneration. In order to sobrevivir (survive), the labor of mothering involves constant negotiations within families and communities, fully thinking through the politics of accountability and belonging.

Chicana motherwork also means maneuvering and mothering across cultural and political borders by creating contradictions that meet at the intersections of racialization, class, and patriarchy. It’s been many, many moons since I fell to the floor sobbing when my neighbor told me that my mother sounded like a broken record when she spoke English. Yet, I can still feel the sting of a little girl made to feel ashamed for this difference. All of these years later, I never imagined that my own little girl would one day come home and tell me that she wished her eyes were blue and that her skin was lighter, that she wishes she could look more like her friends at school. It’s a constant reminder of the work we have to continue to do to remind each other of our humanity. The act of mothering is a process that can be painful and joyous, and the lessons are never ending. Still, the truth remains that I hope to give to my daughter as much of me as my mother (and father) gave to us while remaining committed to myself, a lesson that I hope my daughter will also embrace.

_________________________________________________________

Michelle Téllez is an interdisciplinary scholar trained in sociology, community studies, and education who teaches in the School of Humanities, Arts and Cultural Studies and the Masters in Social Justice and Human Rights program at the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University. In her twenty years of community engagement and activism, she has been involved in multiple projects for change at the grassroots level utilizing critical pedagogy, principles of sustainability, community based arts, performance, and visual media. Her writing and research projects seek to uncover the stories of identity, transnational community formation, migration, autonomy and resistance. She is a founding member of the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network, and is on the editorial review board for Chicana/Latina Studies: The Journal of Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social.

Michelle Téllez is an interdisciplinary scholar trained in sociology, community studies, and education who teaches in the School of Humanities, Arts and Cultural Studies and the Masters in Social Justice and Human Rights program at the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University. In her twenty years of community engagement and activism, she has been involved in multiple projects for change at the grassroots level utilizing critical pedagogy, principles of sustainability, community based arts, performance, and visual media. Her writing and research projects seek to uncover the stories of identity, transnational community formation, migration, autonomy and resistance. She is a founding member of the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network, and is on the editorial review board for Chicana/Latina Studies: The Journal of Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social.

4 Comments