Why Is Academic Writing So Beautiful? Notes on Black Feminist Scholarship

The title of this piece responds to Joshua Rothman’s recent essay for the New Yorker blog, “Why Is Academic Writing So Academic?”, which is itself a response to Nicholas Kristof’s call for academics to engage in public debate. Both Rothman, a writer and editor who considered a career in academia, and Matthew Pratt Guterl, a professor at Brown, have productively moved the Kristof-inspired conversation beyond an insistence that academics do write meaningful pieces for a broader public—a point that seems obvious to most people who aren’t Kristof—and toward the issue of academic prose itself. Rothman thinks academic writing is “knotty and strange, remote and insular, technical and specialized, forbidding and clannish… because academia has become that way.” Guterl agrees that “academic writing is now more specialized… than ever before,” but blames the publishing industry and the reading public’s presumably waning “taste for complexity” rather than academics themselves.

As an academic who not only writes for a living but thinks, talks, and teaches about writing incessantly, I read these pieces with interest. But as a literary critic in the field of African American Studies, I found them disconcerting, because the very idea that “academic writing” is a forbiddingly “specialized” form ignores the black feminist critics who have been redefining scholarly prose for the last 40 years.

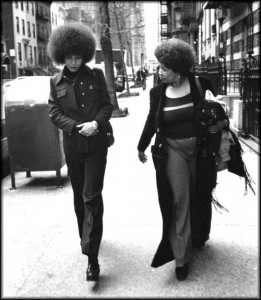

Ever since a 25-year-old Angela Davis structured a lecture on liberation around the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in 1969, black feminist academics have been writing with resounding clarity about the social stakes of literature. So the creators of field-changing “academic writing” that come to my mind are models of lucidity: Mary Helen Washington, Barbara Christian, Hazel Carby, Deborah McDowell, Valerie Smith, Cheryl Wall, Farah Jasmine Griffin, and Elizabeth Alexander, to name only a few. To me, these writers have always represented a particular aesthetic strand of African American cultural criticism—one distinguished by an understatement and elegance that I associate with Billie Holiday’s aesthetic of the cool and Toni Morrison’s dictum that “the language must not sweat.” Their work does not announce the labor of its own intellectual rigor. It is a pleasure to read.

A genealogy of this prose style (and others, such as the verve we might associate with Ann du Cille, Patricia Williams, and Daphne Brooks) deserves deeper analysis than I can perform here. But such analysis would begin with the fact that black feminist scholarship was pioneered by creative writers who were also critics: Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara, Sherley Anne Williams, Gayl Jones, Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison. As Farah Jasmine Griffin stated in a 1999 interview with editor Charles Rowell, these writers inspired a generation of black feminist critics to develop a style that was not only “rigorous and sophisticated” but also “lyrical”: “the voice of the critic as writer.” Speaking of her own scholarly development, Griffin describes a turning-point at which she decided, “I cannot write about black women and black women’s texts in a language that I find ugly.” She needed to honor “the voice of the [primary] texts, the language of our music, the language and just the richness of black voices.”

For the black feminist tradition of academic writing I am describing, this has never meant simplifying one’s ideas, rejecting critical theory, or aiming for immediate accessibility; it has meant taking responsibility for one’s own language of complex thought and presenting ideas in a way that invites understanding. And—crucially—it has meant deciding to do so in the 1980s and 1990s, at the very moment when the specialized vocabulary and complex syntax of poststructuralist theory was in vogue. The fact that “difficult” academic writing has its own value and purpose is another subject. My point here is that before we engage in hand-wringing about the way academics are forced to write, we should recall black women critics who intentionally pioneered and sustain a tradition of understated, beautiful prose.

But let me, as literary critics are trained to do, give examples. I will select a mere handful of literary scholars—the incompleteness of this sample is my point—while showing how they handle maneuvers that scholars in the humanities must generally make: explaining the purpose and arguments of their books; relating and revising others’ critical terms; and closely reading primary texts. Their sentences structures are complex and their formulations require attention. But let’s be clear: an attentive undergraduate student could comprehend them.

Here is how Hazel Carby explains one purpose of her 1987 book, Reconstructing Womanhood: “This historical account questions those strands of contemporary feminist historiography and literary criticism which seek to establish the existence of an American sisterhood between black and white women… Only by confronting this history of difference can we hope to understand the boundaries that separate white feminists from all women of color” (6).

Cheryl Wall says of her 2005 study of contemporary black women’s fiction, “Worrying the Line argues that it is at those moments when the quest for answers to the genealogical search is thwarted, when the only access to the past comes from what [Toni] Morrison describes in “Rootedness” as “another way of knowing,” that these texts are most likely to subvert the conditions of literary tradition so that the connection to the past can be forged nevertheless. Through memory, music, dreams, and ritual, it is” (9).

Cheryl Wall says of her 2005 study of contemporary black women’s fiction, “Worrying the Line argues that it is at those moments when the quest for answers to the genealogical search is thwarted, when the only access to the past comes from what [Toni] Morrison describes in “Rootedness” as “another way of knowing,” that these texts are most likely to subvert the conditions of literary tradition so that the connection to the past can be forged nevertheless. Through memory, music, dreams, and ritual, it is” (9).

Valerie Smith defines a complex term simply: “To describe the interactions of race and gender as they shape lives and social practices, Kimberlé Crenshaw has coined the term ‘intersectionality’” (Not Just Race, Not Just Gender, 1998, xiii-xiv).

Farah Jasmine Griffin adds nuance to a critical concept she wishes to deploy in her own study: “My use of ‘safe space’ seeks to complicate [Patricia Hill] Collins’s definition. First, hegemonic ideology can exist even in spaces of resistance. Second, these sites are more often the locus of sustenance and preservation than resistance. While sustenance and preservation are necessary components of resistance, I do not believe they are in and of themselves resistive acts. Moreover, safe spaces can be very conservative spaces as well” (Who Set You Flowin’, 1995, 9).

Farah Jasmine Griffin adds nuance to a critical concept she wishes to deploy in her own study: “My use of ‘safe space’ seeks to complicate [Patricia Hill] Collins’s definition. First, hegemonic ideology can exist even in spaces of resistance. Second, these sites are more often the locus of sustenance and preservation than resistance. While sustenance and preservation are necessary components of resistance, I do not believe they are in and of themselves resistive acts. Moreover, safe spaces can be very conservative spaces as well” (Who Set You Flowin’, 1995, 9).

Elizabeth Alexander deploys the specialized vocabulary of poetics to read Rita Dove’s “Geometry”: “The power of the iambic pentameter in the first line, ‘I prove a theorem and the house expands,’ is the sly joke of the poem; she leads with her high card as though to say, I can do this, watch me do this, both cleverly invoking and moving beyond an entire literary tradition that has rarely recognized the complex subjectivity of black girls” (Power and Possibility, 2007, 55).

Along with the many emerging scholars who extend this critical line (including Salamishah Tillet, Eve Dunbar, and Courtney Thorsson), these writers remind us that academics are not hapless victims of the job market or publishing industry. They make choices about how they write, whom they select as models, and which models they recommend to their students. At the very least, the sampling above—culled from different stages of scholars’ careers—aims to ease graduate students’ concerns that they must write convoluted prose to be “real” scholars. There is no reason why Rothman’s presumably clear and meticulous work should have been compared by his graduate school colleagues at Harvard to “something you’d read in a magazine” rather than to “a scholarly article by Imani Perry.” Moreover, it is misleading and alienating to suggest that the books scholars publish with university presses are intended for other academics alone. This is not the case. Indeed, we should be highly suspicious of claims that humanities scholarship becomes “unreadable” at the very moment when black women’s voices enter that realm with the painstaking clarity I have sought to reveal.

I trust I am not alone in admiring far more scholar-writers than I can name, which means that the future of academic writing is in good hands. Ours.

_________________________________________

Emily J. Lordi is an assistant professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the author of Black Resonance: Iconic Women Singers and African American Literature (Rutgers, 2013). Her music reviews have appeared on such sites as The Feminist Wire, New Black Man, and The Root. She is working on a new book on soul.

Emily J. Lordi is an assistant professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the author of Black Resonance: Iconic Women Singers and African American Literature (Rutgers, 2013). Her music reviews have appeared on such sites as The Feminist Wire, New Black Man, and The Root. She is working on a new book on soul.

Pingback: Professors as Public Intellectuals: A Reader | the becoming radical

Pingback: Institute of the Black World » The war on black intellectuals: What (mostly) white men keep getting wrong about public scholarship