Broken Mothers, Shattered Daughters: For Women Who Have Loved and Survived [Trigger Warning]

By Amoni Thompson

Broken mothers raising shattered daughters reflecting familiar suns.

Little black girls like me were always in some kind of trouble. Whether we spoke at the wrong moment, had one too many questions, or sat on the couch with our legs too far apart. We were the ones who were always too talkative. So, we made ourselves speak less. They told us we were too sensitive, so we learned to hate mornings and anything that didn’t remind us of our dark closets. They told us we were always into things. So, we stayed still, holding questions like daggers against the pink matter of our jaws. We spent Sunday mornings holding hands, bleeding fear on our stale, white dresses while brushing tears on our elbow-length gloves. No one ever wanted to know if we were okay. After a while, we stopped caring too. We figured, what did it matter? Telling the truth only made you lonely.

A disturbing chill ran the length of my spine the night I told my grandmother how I really got that yeast infection when I was ten. For some reason, she wasn’t as surprised as I had imagined. My ten year old body was thrown into shock, because her anger was with me…and not him.

“Why would you tell your mother such a lie?!” she yelled.

“I promise it’s not a lie, I promise…” I scrambled. “Please believe me! I-I’m…I’m sooooo sorry.”

And there I was, apologizing for my pain. I could buy out all the farms in my county with the many times I continued to do this throughout my life. I lived in being “sorry” so much, my existence felt like an apology. My desire to be the most polite and charming southern girlchild trumped my need to be heard. I watched grandma scream until she finally told my mother and me to get the hell out of her house. This memory has become a tattoo of a lover’s name upon my soul. I know I need to move on, but for some reason I keep recalling the hurtful moments over and over again trying to find what I did wrong. The 10 year old in me is still standing by the porch steps desperately waiting for the words that left my grandmother so shaken and breathless. I needed the woman I loved to tell me I was still her “good little girl,” and to tell me that I wasn’t a problem.

What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?

—Audre Lorde, Sister Ousider, The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action

There are some things even silence can’t keep quiet. Despite your many attempts at repression, neglected truths find a way to gnaw an aching hole in your door of a heart. I remember nights as a curious, glossy-eyed girl who would peek behind my grandmother’s bedroom door to see what was so mysterious about this private space she claimed. There with the lights turned off, I would find her sitting in her rocking chair, allowing the burgundy cushioned furniture to rock her into meditation. I wondered about all the things she was remembering in that moment, all the things she promised years ago she would forget. How many times did she sit adding up all her wrongs behind these closed doors? How many times did she think my sexual abuse was her fault; believing she had let the monster in after she spent years running from it herself? Was anyone there to hold her in her pain? Or tell her that she was never responsible?

It is true, “I am a reflection of my mother’s secret poetry as well as of her hidden angers.” But, I am also a reflection of the many screaming wounds my grandmother was warned to keep quiet. She was advised by the people she thought would protect her to not make any trouble. It took me a while to learn that all the women in my family, women who had mothered me, carried the scars of violation and betrayal. Fear became the lullaby we sang to each other to soothe the broken pieces. From the moment we learned to walk, we understood that there was not yet a language discovered that would allow us to openly discuss our struggles without being dismissively labeled talkative, sensitive, always into things, paranoid, or just plum crazy. We had learned to live and love in homes with crooked rooms. We had learned to live and survive as my grandmother had; with our mouths slightly parted, dreaming our words into existence. Carrying only our scars and wounds, we had to create a vision of survival for ourselves.

Broken mothers raising shattered daughters reflecting familiar suns.

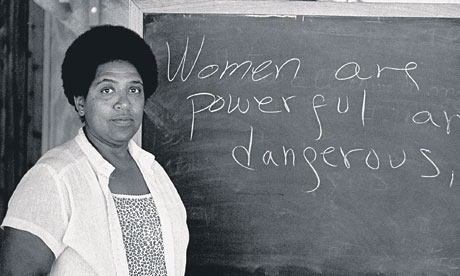

I was only in high school when I read a digital copy of Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” I was hungry for the voices and words of radical black women. Women who were not afraid to speak no matter who was around. Women who refused to be destroyed.

We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and our selves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid.

—Audre Lorde, Sister Ousider, The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action

I’ve come to see Audre Lorde as a possibility model (as sista warrior Laverne Cox coined). She is someone who has shown me that the politics of survival can be re-imagined. Someone who has shown me that it is possible to dream and live in transformation. Through my first creased corner copy of Sister Outsider, I learned that all the silences I thought would protect me would never be able to heal me. Neither will it save me from the complexities of life as a Black womyn in America. There is a language that can communicate the depth of my grandmother’s woundedness and that of other women who were taught that fear was the only language available. From Audre Lorde, I learned that there was another way to survive that honored my fragmentation and my voice; one that’s driven by love and resistance. Her words and legacy live on as the blueprint. In closing, I’d like to leave the words of Damita Jo, an outreach education coordinator for a rape relief program in Seattle, who once wrote this message in a “thank you” letter to Audre Lorde, stating what she had learned from Lorde’s poetry, “No, I am not invisible. No, I am not a vessel for any type of destruction. I am real. My sister told me so.”

Dedicated to my mother, grandmother, Aunt Lorie, Aunt Pam, and Jasmine.

_________________________________________________________

Amoni Thompson, a native of Lumberton, NC, is a UNCF/Mellon-Mays Fellow at Spelman College, where she is completing a B.A. in Comparative Women’s Studies with a minor in Creative Writing. Amoni’s research studies black lesbian feminist poet Audre Lorde and her theories concerning the erotic as healing power for women of color. Amoni recently presented “Maati and My Mother’s Mortar: A Poetic Exploration 20 Years Later” at the 1st Audre Lorde Seminar Colloquium held at Spelman in 2012. A black feminist scholar-activist/poet, Amoni was recently a student reader for the Decatur Book Festival’s 2nd Annual Poetry Reading. She is also active in several organizations, including the Violence against Women Brigade, which is a group of informed and socially conscious women who are campaigning for the eradication of misogyny on college campuses and beyond. Amoni is also a co-facilitator of SisterFire at Spelman, a women’s-only open mic and creative arts healing space. Additionally, she interns at the Southeastern Family Violence Center in her hometown, where she helps to facilitate domestic violence education/self-empowerment classes. Amoni is currently residing in Rabat, Morocco, studying the history of Moroccan women’s resistance and writing poetry. She believes love and mangoes are powerful healing tools.

Amoni Thompson, a native of Lumberton, NC, is a UNCF/Mellon-Mays Fellow at Spelman College, where she is completing a B.A. in Comparative Women’s Studies with a minor in Creative Writing. Amoni’s research studies black lesbian feminist poet Audre Lorde and her theories concerning the erotic as healing power for women of color. Amoni recently presented “Maati and My Mother’s Mortar: A Poetic Exploration 20 Years Later” at the 1st Audre Lorde Seminar Colloquium held at Spelman in 2012. A black feminist scholar-activist/poet, Amoni was recently a student reader for the Decatur Book Festival’s 2nd Annual Poetry Reading. She is also active in several organizations, including the Violence against Women Brigade, which is a group of informed and socially conscious women who are campaigning for the eradication of misogyny on college campuses and beyond. Amoni is also a co-facilitator of SisterFire at Spelman, a women’s-only open mic and creative arts healing space. Additionally, she interns at the Southeastern Family Violence Center in her hometown, where she helps to facilitate domestic violence education/self-empowerment classes. Amoni is currently residing in Rabat, Morocco, studying the history of Moroccan women’s resistance and writing poetry. She believes love and mangoes are powerful healing tools.

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire