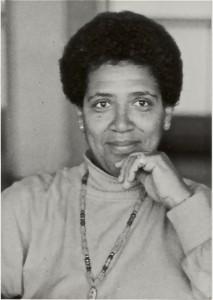

Prologue: Audre Lorde – Word and Action

By Guest Contributor on February 18, 2014By Jewelle Gomez

I’ve been thinking about Audre more than usual because I recently celebrated the 20th anniversary of the publication of my black, feminist, lesbian, vampire novel, The Gilda Stories. After Nancy Bereano, the book’s publisher, Audre shares a big responsibility for my novel’s existence. How a quote from one of her poems came to be an epigram for the novel is a capsule story of my relationship to her and her work.

Audre’s poem, “Prologue,” has weaved in and out of my writing life for thirty years, tying together my novel and the first book of poems I wrote as well as my sense of my political self. Audre has written many poems which are more famous or thought of as more ‘activist’; yet her poem, ‘Prologue,’ remains for me the most succinct, emotionally full and personal of her poems. It is a graphic reflection of her belief in the power of the word to lead to action, her belief in the need for words to lead to action.

This started in the 1970s, when I self-published my first chapbook of poetry. I used her book, From a Land Where Other People Live, as a literal model. I poured over those poems, the layout, typeface, order and positioning as if I was making a new dress from the pattern pieces of a familiar favorite. That’s when I first discovered ‘Prologue.’ It’s a poem I always remembered, especially because of the final stanza:

…Somewhere in the landscape past noon

I shall leave a dark print of the me that I am

and who I am not

etched in a shadow

of angry and remembered lovingand their ghosts will move

whispering through them

with me none the wiser

for they will have buried me

either in shame

or in peace.

And the grasses will still be

Singing.

The stanza and the poem as a whole has an elemental, organic spirituality located in the belief that her life would be transmuted and feed the earth from which would spring the future, the grasses that “will still be singing.”

Of course, when I first read the poem, which is long and lyrical, I didn’t understand most of it. I’d studied journalism not poetry, but I knew from the Black Arts Movement that art in general and poetry in particular had its own heat and urgency and could fuel action. So I always returned to it, knowing it better over the years. It was the ‘70s, a time for feminist poets who rallied women in women’s bookstores across the country.

After dissecting Audre’s collection and constructing my own, I had a burst of bravery and decided to send my chapbook to her. It was still possible then to look up somebody’s address in the telephone book, so I mailed Audre that first effort, “The Lipstick Papers (1979).” At the time I didn’t expect her to actually remember me from our various public encounters, but I just wanted the book to go to its progenitor.

Weeks later, I came home to a startling surprise: Audre had left me a telephone message congratulating me and more importantly, giving me critique on a couple of poems. A simple congrats would have been easy, but she went further into the work to help me go further into the work. She jumped into my words like a collaborator which is, of course, what she was for all of us who cared.

Then in the late 1980s, continuing to push the bounds of my New England sense of propriety, I rashly asked Audre if she’d read my short story collection, which featured as the central figure the vampire Gilda, who is Black, lesbian, and feminist.

Audre was pretty direct as she was most of the time so she said she didn’t care for vampire fiction and she wasn’t that into short stories, but yes, she would read them. Before I printed them out to give to her, I looked through her work desperately for a quote to use as an epigram. That wasn’t a craven effort at gaining her approval, but actually something I did—and still do—almost every time I start a speech or essay. I go to Audre’s work as one goes to the village well to draw up the cool fresh water that will regenerate thinking and give a framework to the writing.

So when I gathered my courage this time I returned to “Prologue” and found this line:

At night sleep locks me into an echoless coffin

sometimes at noon I dream

there is nothing to fear…

The line was so perfect an introduction to my Black lesbian feminist vampire novel. It was a magical gift. I don’t know what I hoped for in handing Audre the manuscript, but again it seemed important that she have it in her possession. Weeks later she was giving me a ride in her car from some event and I was way too anxious to ask if she’d read my book, so we just gossiped.

As we pulled over, before I got out she said crisply: she had read the book and, she pronounced: I needed to go back and rewrite it because it was not short stories but a novel…a good novel.

From then on, Audre was an actual voice in my life not simply the shadow of words on a page or voice on an answering machine. She spoke to me in the Caribbean lilt we all came to know, reached across our differences and made the world clearer. This is as it should be for any writer with a conscience and commitment to her community—they live for us in their words. It is for us to remember to use the well of wisdom and insight they’ve created. We are abundantly wealthy and Audre remains one of our most treasured resources. Achè.

____________________________________________________

Jewelle Gomez (Cape Verdean/Ioway/Wampanoag), writer and cultural worker, is the author of seven books including the double Lambda Literary Award-winning, Black vampire novel, THE GILDA STORIES, in print continuously since 1991. She adapted the book for the stage. “Bones and Ash” was commissioned and performed by Urban Bush Women Company in 13 US cities. Her most recent play, “Waiting for Giovanni,” looked at an imagined moment in the life of James Baldwin.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire