Personal is Political: Sexual Identity and “Nigerian Culture”

By Adejoke Tugbiyele

I was born in Brooklyn, New York to Nigerian parents. Like most children of immigrants, it became clear to me that survival depended on how well I could code-switch between American and Nigerian culture. At home, I was discouraged from talking back or speaking up. At school, lack of participation could negatively affect my grade.

As a young woman, cultural lines became even more defined. I remember getting into a heated argument with my Mother one Saturday because I wanted to practice sketching/drawing instead of cooking. Similarly, I remember my father’s advice to me when I opened a small business in Newark, New Jersey with my husband at the time: “Just because you’re running a business doesn’t mean you should not keep your house clean.” I am pretty sure my being a woman had everything to do with those words of advice.

After summoning the courage to leave my husband and come out of the closet to parents and other family members, it became clear that my Nigerian identity would not only be questioned, but attacked by close relatives. I had no frame of reference as a child of African parents on how to go about exploring my sexuality. Any Nigerian or African I suspected might be gay either distanced themselves or seemed even more judgmental than most. “Bible-talk” was in heavy use among my circle of friends and family. It was a rather lonely and depressing experience. Art became the vehicle for self-expression and healing, and now I turn to activism against injustice and inequality.

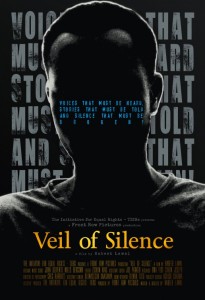

I spent the latter part of 2013 living and working in Nigeria under a Fulbright Scholarship. My research dealt with the cross-section of spirituality and sexuality among LGBTQ communities living in that country and how they navigate a largely conservative, religious society. My first three months in Lagos were very productive. I attended gay parties with my friend and activist Williams Rashidi, with whom I had many engaging debates about how to bring about change in the minds of others towards queer communities. I also filmed a panel discussion organized by The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERS) at their screening of the new documentary Veil of Silence. I visited the Shrine of Osun, based in Oshogbo, and interviewed a Yoruba Priest and Priestess about homosexuality within traditional Yoruba culture. I engaged LGBTQ communities in Lagos, as well as Nigerians abroad, about what it meant for them to be queer and Nigerian. The responses I got mirrored many of the issues one would find in mainstream society. Just like straight people, queer people also need access to good health care, clean drinking water, a better educational system, and so on. In other words, LGBTQ people are people, and their sexuality does not necessarily make their daily experiences remarkably different from the average Nigerian, African or global citizen.

My research and my self became threatened when President Goodluck Jonathan signed the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMP) earlier this year. It is essentially an anti-gay law, as it includes the banning of all gay parties and organizations. It also states that any public and private display of affection is punishable with 10 years imprisonment. Practically overnight, LGBTQ people, who are worried about things like getting to work on-time just like everyone else, now fear leaving their homes altogether. Their beloved country had just labeled them criminals. I, as an out-lesbian artist living in Nigeria at the time, had also been criminalized. Police have essentially enacted a “witch-hunt” for gays, and these were just the stories we could access in the papers. Apparently, other evils have emerged within the past two weeks that have not been covered in Nigerian news outlets. For instance, I just learned that a “gay convert” just stabbed his gay friend to death in Lagos last weekend. The fear this new law has raised in LGBTQ communities has led people to turn on each other.

The fundamental problem with Nigeria’s anti-gay law is that it unites supposed enemies within Muslim and Christian sects, and it validates and empowers their extremist, conservative views on how we ought to live. The empowerment of hate groups is not only happening in Nigeria. With the events unfolding in Russia regarding the Sochi Olympics, the world is beginning to wake up to LGBTQ rights. Along those lines, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder recently argued that LGBTQ rights are one of “the civil rights challenges of our time.”

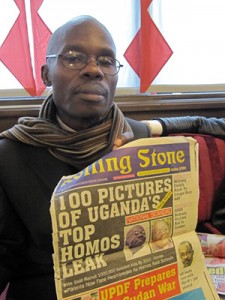

I am concerned, however, that the West would not be pressing this hard on global LGBTQ rights had the events of the Sochi Olympic Games not unfolded. After all, the “corrective rape” of lesbians has been rampant in places like South Africa for decades now. And it was just over three years ago when LGBTQ activist David Kato was brutally murdered in Uganda. Further, the extortion and bribery of LGBTQ people has become common place in Nigeria, as depicted in a handful of homophobic Nollywood films, such as Hideous Affair (2010). “The Video Closet” by Lindsey Green-Simms and Unoma Azuah thoughfully examines how mainstream homophobic views are reflected in within the regulated Nollywood film industry. Regarding sexual identity, we can argue that this historically dominant view still holds—the African/Black body as “less important” than that of the Western/White body. The sexual revolution that begun in the West must not fall prey to the mistakes of the feminist revolution in the U.S. in order to be considered truly global. We must remember that the emergence of writers like Angela Y. Davis, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Audre Lorde was a response to racist feminisms that excluded Black women. Similarly, African female writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie have emerged to continue the feminist wave across the Atlantic. In short, with all the work that still needs to be done globally to combat discrimination, the additional fight for sexual rights in Africa and throughout the diaspora makes the work even more difficult. The sexual revolution must be global and inclusive of all peoples for it to have lasting impact both socially and politically.

Internal problems certainly don’t help. In the case of Nigeria, there are still too many parents that won’t allow their Yoruba daughters to marry Igbo sons. Many Igbo people are calling on the federal government to apologize for the genocide of Biafra. A lot of Hausa people in the North believe that Nigeria belongs to them, since it was handed to them one hundred years ago by the British during the Amalgamation of 1914. Therefore, national unity and identity is not as defined in Nigeria as it is in the United States. To a large extent, believing that the masses will “do nothing” is partly what empowers the federal government to sign such hateful and demeaning laws in the first place.

The other thing that empowers President Goodluck Jonathan is the growing economic (oil) wealth of the country, to the extent that Nigeria does not hesitate to reject aid from the West. We have heard senior members of government in Nigeria claim that the West should allow it to govern its own people according to Nigerian culture. I chuckle each time I hear this ridiculous argument. First, Nigerian government officials either don’t realize or have forgotten that it was the West (in partnership with tribal chiefs/kings) that gave birth to the very first “Nigerian culture” in 1914. Second, the so-called Nigerian culture that emerged after independence had more to do with the desire to control natural resources locally and very little to do with an alignment of values/beliefs across different ethnic groups. Third, this desperate, last-minute attempt to design a “Nigerian culture” by uniting Muslim and Christian conservatives based on who they hate is not the mark of good leadership, but rather, is cowardice. In short, a top-down, self-defined Nigerian identity simply does not exist, unless the recent hateful move to criminalize innocent people in order to “unite” the country is Goodluck Jonathan’s bizarre idea of defining “Nigerian culture.”

It is important to note, however, that a Nigerian identity in tune with global contemporary shifts has been brewing among the country’s youth over the past two decades. A huge generational gap exists between the elderly and elite few who run the country and the majority of people who are thirty-five years old and younger. Among the youth, a style and fashion exists that weaves contemporary Western aesthetics with traditional African patterns. I could hear it in the music, where afro-beat and rap music are married together in creative ways that force one to come up with new dance moves. Was it not the international pop-star Beyoncé who recently included Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her pro-feminist anthem “Flawless?” I could feel it in the art, where people have begun thinking outside-the-box by taking old, discarded materials and re-purposing them in ways that give the pieces new life.

A renaissance has already begun, but the President’s latest move attempts to discourage and disrupt this creative evolution in many ways. The anti-gay law encourages a new national identity based on hate, ignorance and discrimination, rather than love, understanding and tolerance. Anything that could look like a renaissance is moving at a snail’s pace, considering the work of musical geniuses like Fela Anikulapo Kuti and literary greats Wole Soyinka and the late Chinua Achebe. This is, in large part, due to the narrow, conservative mindset that defines Nigeria’s government and religious institutions.

I just directed a short experimental film entitled AfroOdyssey IV: 100 Years Later. It weaves together many complex issues, raises questions about what it means to be LGBTQ and Nigerian in the 21st century, and suggests the need for dialogue. AfroOdyssey IV is made possible by the courageous and dedicated work of my production team: Olushola A. Cole (Associate Producer/performer/musician), Lindsey Bauer (performer), Anne M. Boisvert (set-production assistant), Davis Mac-Iyalla (activist/contributor), and Michael Akanji (activist/contributor). Through dance, costume, music and voice, we critique conservative, religious machinations within Nigeria concerning sexual identity and, to a lesser extent, womanhood. This project, well underway before the signing of the bill, is now critically important as an educational tool, as well as a vehicle of empowerment for queer people and allies, both within Nigeria and beyond. In the film, the church is both the site of struggle and celebration. But the film goes a bit further by depicting what takes place outside the church and beyond mainstream view, a thriving underground gay scene, as well as traditional spiritual practices that have to “hide” from the damnation of powerful and conservative religious institutions. Fortunately, historical knowledge exists proving that homosexuality and same-sex marriage have always been a part of various African cultures, well before the arrival of Christianity. And today, there are those who have found a home for their sexuality within the sacred walls of open, progressive and inclusive Churches. With the SSMP Act now signed into law, the next series, AfroOdyssey V, is bound to have even more political charge than the others. Stay tuned.

_________________________________________________________

Adejoke Tugbiyele is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, writer, activist and Fulbright scholar. Her work has been exhibited at The Jewish Museum of New York, The Reginald F. Lewis Museum, The Museum of Arts and Design, The Goethe-Institut (Washington, DC), The United Nations Headquarters (New York), and The Centre for Contemporary Art (CCALagos), among others. Her work has been published in The New York Times, CNN International, and The Huffington Post. She graduated with a Master of Fine Arts from Maryland Institute College of Art and is currently an Artist-in-Residence at Gallery Aferro. Join the movement. Follow AfroOdyssey IV on Twitter and Facebook for updates.

Pingback: Anti-Gay Laws and the Unification of Nigeria