Mumia on Religion, Empire, and Gender

By Mark Lewis Taylor

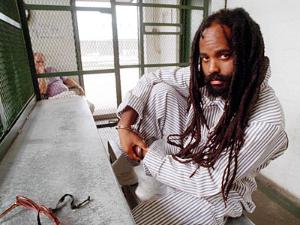

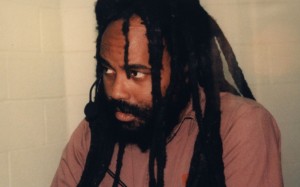

While Mumia endured 50 days in solitary confinement, transiting from 29 years on death row to the general prison population in 2012, I spoke with him by phone. He was persevering, but somewhat weaker of voice than in previous phone visits. Life in solitary, he wrote, could be worse than death row.

While Mumia endured 50 days in solitary confinement, transiting from 29 years on death row to the general prison population in 2012, I spoke with him by phone. He was persevering, but somewhat weaker of voice than in previous phone visits. Life in solitary, he wrote, could be worse than death row.

But still, even from there he prepared two essays for my 2012 Critical Race Theory class at Princeton Seminary. They appeared in my Dropbox after he finally emerged from solitary.

One essay written and recorded was “Church of Caesar or Church of Christ: Reflections on the ‘Other Race.’”

The “other race” is a phrase Mumia takes from Mary Magdalene’s reputed comment in the Gnostic text called “Pistis Sophia,” lamenting apostle Peter’s “hatred of the female race.” Mumia’s essay then exposes imperialized Christianity for its “hideously repressive” treatment of women as an “other race.”

“To this very day,” comments Mumia, “the very notion of the feminine divine is seen as, if not exactly heretical, at least quite odd.” He criticizes church patriarchs’ “anti-eroticism, misogyny, anti-natural – anti-life – principle.” He concludes, lifting up for remembrance the sacred feminine figure, Egypt’s Isis.

Mumia leaves readers pondering the divine feminine as “what might have been” – a counter-imperial, women-celebrating politics of faith, love and justice. He muses thus while he himself is incarcerated in one of the most imperialized and Christianized polities, Prison Nation USA.

Addressing women’s liberatory issues is no new thing for Mumia. His chapter, “A Woman’s Party,” in We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party, is one of the best treatments of women’s essential contribution to the Panthers.

Some might think Mumia’s essay belonged more in my feminist theology course. But it is vintage Mumia to write in ways that resist compartmentalizing oppressions. He writes of race, empire, sexuality and religion together, recognizing what theorists discuss as “intersections” or “assemblages” of different systems of political privilege.

Some might think Mumia’s essay belonged more in my feminist theology course. But it is vintage Mumia to write in ways that resist compartmentalizing oppressions. He writes of race, empire, sexuality and religion together, recognizing what theorists discuss as “intersections” or “assemblages” of different systems of political privilege.

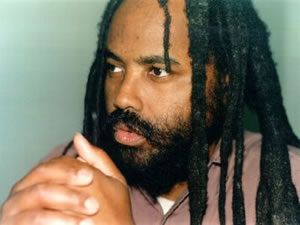

Today’s feminist and other political thinkers will find points in Mumia’s thinking to challenge. That’s all good. He’s no icon above criticism. His perspectives, though, are essential. As a “voice of the voiceless” he brings standpoints usually excluded by university scholars. Truth is more likely if forged in dialogue with voices like Mumia’s, seasoned by life-long activism amid the repressed and excluded.

Mumia’s striking communication skills and trenchant political analyses are why I founded Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal (EMAJ), co-coordinated now with Professor Johanna Fernandez who shapes much of the movement along with Pam and Ramona Africa and others.

I first discovered Mumia’s work while buying a homeless street newspaper in New York City in the early 1990s. I began using many of Mumia’s writings in graduate-level classes. His writings ignited student thinking on the politics of imprisonment, policing and the death penalty.

I resolved that if officials ever signed a death warrant to silence Mumia, “I couldn’t live my life as usual” (as I muttered to myself then). So, when Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge signed Mumia’s death warrant in 1995, I requested educators’ support for Mumia. This began years of organizing press conferences, newspaper ads, and educators’ contributions to the larger Mumia movement.

Scholars Cornel West, Angela Y. Davis and Manning Marable were early to the fore. Hundreds of colleagues signed ads for Mumia, from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and other regional schools.

Scholars Cornel West, Angela Y. Davis and Manning Marable were early to the fore. Hundreds of colleagues signed ads for Mumia, from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and other regional schools.

These included Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak of Columbia University, also Achille Mbembe, E. Ann Matter, Ann Farnsworth-Alvear, Farah Jasmine Griffin (all four, then at UPENN), and Rebecca Alpert (one of many at Temple University) – all with others signing the ad for Mumia in 1995’s Philadelphia Daily News. A full-page ad in The New York Times followed, headlined by Toni Morrison, Frances Fox Piven, Patricia Williams, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Sonia Sanchez, among others.

What the future holds for Mumia as contributor to feminist theory, religious studies, and to education generally, I cannot predict. But I am sure that educators engaging Mumia’s writings, encountering his humanity and dignity, will be the better for it. It has long been so, and, happily, a younger generation of students and teachers continue to draw inspiration from him.

****

Get involved with the Free Mumia Campaign

Bring Mumia Home Website

Bring Mumia Home on Twitter

“60 for Mumia’s 60th Birthday” IndieGoGo Campaign

Free Mumia Petition (Change.org)

_________________________________________________________

Mark Lewis Taylor is Professor, Religion & Society, Princeton Theological Seminary. He is founder of Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal (EMAJ) and presently a co-coordinator of EMAJ. He is the author of numerous books and essays, among them The Executed God: The Way of the Cross in Lockdown America (2001), and most recently, The Theological and the Political: On the Weight of the World (2011).

Mark Lewis Taylor is Professor, Religion & Society, Princeton Theological Seminary. He is founder of Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal (EMAJ) and presently a co-coordinator of EMAJ. He is the author of numerous books and essays, among them The Executed God: The Way of the Cross in Lockdown America (2001), and most recently, The Theological and the Political: On the Weight of the World (2011).

Pingback: Moving on the Wires: This Week’s News and Posts | Aker: Futuristically Ancient