By Darlena Cunha

Welcome to the UFC’s (Unified Feminists Championship) main event tonight, folks. Refereeing this good match is the esteemed bell hooks, known for her accessibility and sharp wit. In the red corner, we’ve got Merri Lisa Johnson, standing for postmodern feminist scholars who promote individual choice as a progressive alternative to radical feminism. In the blue corner, Angela McRobbie heralds third-wave feminists who align their views with those women who came before them, stating the fight to get misogyny recognized within the patriarchy is far from over. On the one hand, women are fighting for their individual right to move within the admittedly bigger box we’ve made for ourselves. On the other, women are fighting to increase awareness outside that box, one of their methods being to advocate less movement inside it.

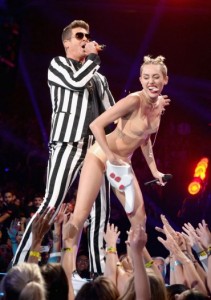

It’s a tricky fight here, mired in theory, jargon, and intellectual strength, which are pitted against societal forces. The fight lines a woman’s personal choice of media consumption, as part of her freedom as a new woman in a post-feminist world, against continuing education of a society already congratulating itself for overcoming its sexist battles and laughing at the old patriarchal messages…by bringing them back in an ‘ironic’ way. hooks shakes hands with our contestants, reminding them that “feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression” (2000, pg. viii). On the top of everyone’s minds, of course, the recent MTV Music Video Awards show, where young Miley Cyrus twerked all over Robin Thicke during his 2013 summer hit and song reviled by many feminists, “Blurred Lines.”

And there’s the bell!

Johnson starts off with a quick shot to the gut, stating that feminism in media should be an individual construct. “What constitutes a “feminist enough” character or series—a common gauge in feminist television and film studies—varies depending on the viewer’s particular situation” (2009, pg. 393).

McRobbie strikes back with a left cross, invoking the film “Bridget Jones’ Diary” for her defense. In the movie, based on a popular column and then book, Bridget is a single woman in her thirties, living a feminist lifestyle but pining for traditional women’s desires, like a husband and family. “Bridget deserves to get what she wants,” McRobbie says. “She ought to be able to find the right man, for the reason that she has negotiated that tricky path which requires being independent, earning her own living, standing up for herself against demeaning comments, remaining funny and good humored throughout, without being angry or too critical of men, without foregoing her femininity, her desires for love and motherhood, her sense of humor and her appealing vulnerability” (2009, pg. 421).

Johnson stumbles a bit as McRobbie has just described, through a media message, the very plight of the carefree woman Johnson is trying to promote. Suddenly her free choice doesn’t seem all that free. Wait! Another jab from McRobbie! She proposes that “through an array of machinations, elements of contemporary popular culture are perniciously effective in regard to this undoing of feminism, while simultaneously appearing to be engaging in a well-informed and even well-intended response to feminism” (2009, pg. 411).

McRobbie has Johnson up against the cage! hooks steps in, breaking up the punches. She reminds the fighters that “in its earliest inception, feminist theory had as its primary goal explaining to women and men how sexist thinking worked and how we could challenge and change it” (2000, pg. 19). This point stuns the fighters back to their corners, and brings to the forefront the Miley performance as the bell signals the end of the round.

Miley Cyrus can get up on stage and twerk to a misogynistic song about blurred lines of consent (even though there are none—if it’s not a yes, it’s a no), where Robin Thicke sings “I know you want it,” leaving everyone to wonder how, in fact, he knows. She has that right as a woman, and she can feel objectified or not, depending on her own personal prerogative. And if she doesn’t feel objectified, as the almost-naked model in Thicke’s video doesn’t feel objectified, are women being objectified?

The audience begins to talk amongst themselves. “Objectification” one commenter notes on The Huffington Post, “doesn’t mean ‘makes people feel bad about themselves.’ Objectification means, ‘causes the viewer to see the performer as an object and not a person.’ It is completely irrelevant whether these dancers felt objectified, whether they were happy or sad to be objectified, or whether anyone at all, performer or audience, was offended by the performance.”

The audience begins to talk amongst themselves. “Objectification” one commenter notes on The Huffington Post, “doesn’t mean ‘makes people feel bad about themselves.’ Objectification means, ‘causes the viewer to see the performer as an object and not a person.’ It is completely irrelevant whether these dancers felt objectified, whether they were happy or sad to be objectified, or whether anyone at all, performer or audience, was offended by the performance.”

hooks agrees, as she oversees the fighters in their corners, right before the second bell. She recalls the issue of Tweeds Magazine she used as an example in her work, “Eating the Other.” In that spread, white and black models seemingly coexist in an Egypt from long ago. Hooks says of it: “for 75 pages Egypt becomes a landscape of dreams, and its darker-skinned people background, scenery to highlight whiteness, and the longing of whites to inhabit, if only for a time, the world of the Other. The point of this photographic attempt at defamiliarization is to distance us from whiteness, so that we will return to it more intently” (1992).

She asserts it is the mainstream’s—the whites’—desire for the romanticized primitive that propels these ads and this imagery forward. She notes that the Egyptian people’s faces are blurred by the camera, their pictures serving as a backdrop to the focal whiteness.

The same could be said for Miley’s Black backup dancers in the context of both racial relations and feminism. The same could be said for Miley herself, and Robin Thicke’s model in the video. The objectification doesn’t have to do with the individuals’ feelings on the matter, it has to do with the audience’s perception of those individuals. With that in mind, the second bell rings, and no one has noticed another academic sneaking into the cage!

What’s this? A tag-team? A tackle from John Fiske stops McRobbie short, sweeping her legs out from under her by invoking a broader cultural context. “The politics of popular culture is progressive, not radical,” he says. “It attempts to enlarge the space within which bottom-up power has to operate. It does not, as does radicalism, try to change the system that distributes that power in the first place” (1989, pg. 56).

But why does attempting to change a system of oppression count as radical, McRobbie wants to know as she grapples for a hold on the ground. “Young women somehow want to reclaim their femininity, without stating exactly why it has been taken away from them” (2009, pg. 420). She struggles to her feet and delivers a strong right hook, attacking Giddens and Beck (1991, 1992) for their writings on individualization. After young women were allowed to break free of the shackles of traditional wife and mother roles, she notes, “individuals are called upon to invent their own structures” (2009, pg. 418). So we must be careful what we choose to create. “The individual is compelled to be the kind of subject who can make the right choices. By these means, new lines and demarcations are drawn between those subjects who are judged responsive to the regime of personal responsibility, and those who fail miserably. . .[Giddens and Beck, 1991, 1992] have no grasp that these [power relations] are productive of new realms of injury and injustice” (2009, pg. 418).

Why so serious, Johnson asks, blocking the hold and delivering a karate kick to the sternum. “Television is one of the ways our culture talks to itself about itself” (2009, pg. 404). If we can’t relax in our own homes with our own decisions about what we find enjoyable, then McRobbie must be assuming women cannot engage in negotiated or oppositional readings of texts (Morley, 1980). She drops an elbow over McRobbie’s eyebrow. Do we now have to ask, Johnson wonders, “whether watching television is in some sense, frankly, like sucking the dick of patriarchy?” (2009, pg. 398). Johnson plies yet another jab to the third-wave feminists saying they “require us to trash the delight that doubles as complicity” (pg. 397). Let women like what they like, she argues. Making those choices is part of feminism.

McRobbie is bleeding profusely, and hooks stops the match for a moment so she can stop the blood, asking everyone to remember that “future feminist movements must necessarily think of feminist education as significant in the eyes of everyone…By failing to create a mass-based educational movement, to teach everyone about feminism, we allow mainstream patriarchal mass media to remain the primary place where folks learn about feminism, and most of what they learn is negative” (2000, pg. 23).

McRobbie has taped up her brow, and comes out with the roundhouse kick of context, agreeing that she does, in fact, view the delight Johnson mentioned as complicity. “There is a quietude and complicity in the manners of generationally specific notions of cool, and more precisely, an uncritical relation to dominant commercially produced sexual representations which actively invoke hostility to assumed feminist positions from the past, in order to endorse a new regime of sexual meanings based on female consent, equality, participation and pleasure, free of politics” (2009, pg. 417).

You can enjoy something but still criticize it, she says. You don’t have to let go of the criticism to prove we’re all past something we’re certainly not yet past. We cannot move from the political realm of feminism before the actual equality there is achieved. For the knock out.

_______________________________________

Darlena Cunha is a former television producer turned stay-at-home mom to twin five-year-old girls. When she’s not parenting, she’s writing novels, freelancing, going to grad school, or blogging at http://parentwin.com. She also writes for The Huffington Post, and has had feminist works published both there and at Fem2pt0.

Darlena Cunha is a former television producer turned stay-at-home mom to twin five-year-old girls. When she’s not parenting, she’s writing novels, freelancing, going to grad school, or blogging at http://parentwin.com. She also writes for The Huffington Post, and has had feminist works published both there and at Fem2pt0.

You may also like...

7 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Notes from the Red Corner: Making Room for Mixed Feelings about Media Culture - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire