A Statement on the Reclamation of All Black Life: For Trayvon, Marissa, & Jordan

By Brothers Writing to Live

We begin this collective statement by proclaiming a truth that has been rehearsed on countless occasions by many before us: The lives, the bodies, the souls, and the minds of Black people matter. And even though the spirit of these United States, since its inception, has been animated by a White supremacist desire for Black death, Black people have long resisted—by way of insurgencies, by way of self-love, by way of our daily living—White racists’ twisted and obsessive fascination with our demise. We live. And we refuse or, rather, refract the racial gaze that would have others view us (and we, ourselves) as markers for someone’s bullet, strange fruit ripe for some state’s lynching (execution) tree, commodified bodies necessary for the mushrooming of public and private prison industries, or mere subjects spoken about/spoken at/spoken over in legal chambers, political halls, and educational institutions.

Indeed, these times are reflective of what anthropologist John L. Jackson has rightly named “racial paranoia.” Like Jackson, every day we witness the tragic, and often, violent results of others’ unfounded suspicion of and lack of trust in differently raced people in this country. And this is too common a phenomenon among those of us who exist on the other side of Whiteness. But we refuse to let the lie of otherness mute the truth of our collective existence and power.

So, we name:

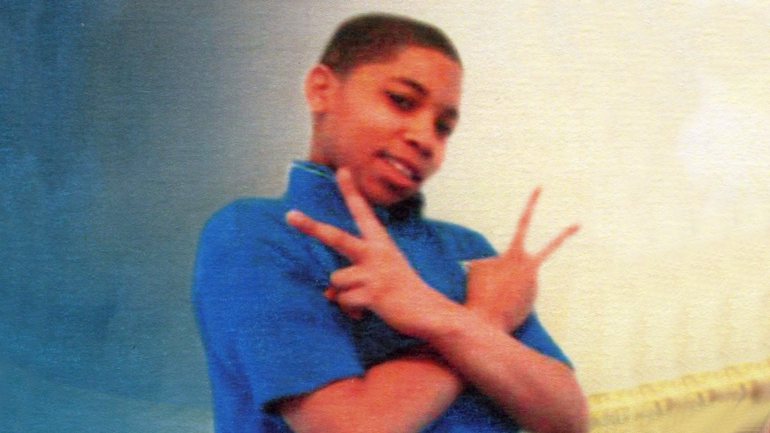

We name the name of Trayvon Martin—a 17-year old Black boy whose life potential was snuffed out by the ammunition of an adult neighborhood watch volunteer-turned-vigilante, George Zimmerman. Zimmerman walks freely today because he was found “not guilty” of charges of manslaughter and second-degree murder by six jurors–five of whom were White. And the victim, Trayvon, a Black teenager who, on his last day alive, donned a hooded sweatshirt, carried a bag of Skittles, and a can of iced tea, has become both signified and signifier. That Black teenager who was someone’s son, brother, friend, classmate and who was shot to death because of another’s suspicion, has now become a representation (a picture on posters and a now iconic visage on social media outlets) for failed justice. That Black boy who should have returned safely to his father’s home—six houses away from where he was shot—has become a caricature whose last bodily posture (that of a dead Black body sprawled out on a lawn) is now used by others as means of performing Trayvoning–another new-aged form of racist folly. Yet, Trayvon is more than a sign. He was a human being, a Black teenager animated by life, who was murdered. He was not the already-dead walking among us even if his murderer failed to see life potential in him. He lived. And so shall his legacy.

We name the name of Marissa Alexander—the 32-year old Black mother who now serves a 20-year sentence for firing a warning shot to protect herself from an abusive partner in the same state that freed Zimmerman for killing a another Black mother’s son. Marissa’s case, unlike Trayvon’s, as pointed out by women like Jamila Aisha Brown, lacked media attention and the type of critical mass that was organized to bring Zimmerman to (in)justice. Like Brown, we too admit that the lives and struggles of Black women, like Marissa, are too often invisibilized. If as Black men we have been shot by the weighty bullets of White supremacist capitalism, Black women, our sisters, have experienced the brunt force of what bell hooks named “White supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” Indeed, Black women must protect themselves against multiple firings at the hands of some men (Black men included) and some White people (White women notwithstanding). Marissa sought to protect herself from a Black man who used his fists to demonstrate power and now stands in need of protection from the forceful blows of a criminal justice system that is shaped by sexism and classism as much as it is shaped by White supremacy. But we stand in solidarity with Marissa, and her children and family, as she fights for justice. And we won’t stop until she is able to walk, to live, free from the type of confinement that heavy steel prison bars make possible and that unjust laws substantiate.

We name the name of Jordan Davis—the 17-year old Black teenager who was shot to death by Michael Dunn, a 46-year old White male, in the same state that released Zimmerman and imprisoned Marissa. Dunn pulled out a gun and released bullets into a Dodge Durango where Jordan and his friends were situated. Dunn, who was upset after having a dispute with the teens about the volume of, what he described to his girlfriend as “thug music”—the type of music he “hates”—ended up killing Jordan that night. He claims that the boys threatened him. He claims that they had a gun. And, like Zimmerman who preceded him as yet another gun-toting murderer of the presumed “suspicious” Black male in the state of Florida, Dunn did not think about the possibility of a young Black boy’s death that tragic evening because in the minds of many, Black boys (“those people,” “thugs”) are already and at all times imagined as lifeless and/or capable of ending the lives of others. According to police, however, they did not find the imagined weapon in the vehicle that supposedly frightened Dunn as is the case of most who suffer from racial panic.

We name any person, any system, and any state intent on destroying Black life as terrorists who have been domesticated in the ways of White supremacy in the master’s house. To echo our sister heroine Audre Lorde, “the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house.” Thus, we resist the gaze that would have us see in ourselves what White racists see in us, which is really what they see in themselves, namely, social death. It is true, indeed, that those who have yet to exist fully in their humanity will never be able to see the humanity, the life, in others. The ethically and morally dead are attracted to death. But, we will live. And we will not stand idle, with closed mouths and lowered fists, as Black folk are deadened by bullets, Black bodies and spirits are destroyed by jail cells, and Black life diminished by the darkness of White supremacy.

We will not die. We cannot die. There’s too much life bubbling over inside of us. And it’s a special kind of life that’s overflowing—the kind that engenders nations and annihilates racial, cultural and economic tyranny. Our freedom is untouchable by evil. Hasn’t it tried and failed embarrassingly?

We were never a “problem.” The possibility of our Black bodies occupying White property—White sidewalks, White stores, White dreams—and dismantling White supremacy’s parasitic bond to this nation’s history is the “problem.” But today, we acknowledge, if it is a problem—it is not ours.

And in that spirit of radical living, we reclaim life.

We don’t choose life. Choosing was never an option. We seize life.

____________________________

Brothers Writing to Live is a group of black cis and trans-men who hail from spaces across the United States. We come from myriad neighborhoods, diverse familial backgrounds, and different life worlds. We are different, indeed. And, yet, in so many ways we are the same. We are black male identified writers whose notions of blackness, manhood, and writing are as assorted as our multifaceted lives. Whether we have come from the red clay roads of Mississippi or the cement paved streets of New York City, through our writings we have mapped out similarities regarding the ways that racism, gender restrictions, capitalism, heteropatriarchy, ableism, economic disenfranchisement, heteronormativity, criminal (in)justice systems, and so much else has shaped the men that we have become and yet to be. This campaign has united the following black male writers:

Kiese Laymon, Writer & Professor at Vassar College

Mychal Denzel Smith, Writer, Mental Health Advocate, & Cultural Critic

Kai M. Green, Writer, Filmmaker, & Ph.D Candidate at USC

Marlon Peterson., Writer & Youth & Community Advocate

Mark Anthony Neal, Writer, Cultural Critic, & Professor at Duke University

Hashim Pipkin, Writer, Cultural Critic, Ph.D. Candidate at Vandebilt University

Wade Davis, II, Writer, LGBTQ Advocate, & Former NFL Player

Darnell L. Moore, Writer & Activist

0 comments