Myths of Progress and Cartographies of Hate

By admin on May 30, 2013By Darnell L. Moore and Monica J. Casper

Definition of HATE

1 a: intense hostility and aversion usually deriving from fear, anger, or sense of injury

b: extreme dislike or antipathy : LOATHING

2 : an object of hatred

3. v: to increase the distance that exists between oneself and the object of hatred; disconnection.

Advocates for social justice have found much to celebrate recently with the legalization of “gay marriage” in state after state. A broad swath of the Northeastern United States now allows same-sex marriage, as do Washington State, Minnesota, and Iowa. LGBTQ and mainstream news media have understandably touted the changes as victories and as evidence of progress on the sexual freedom front.

We are, at the same time, purportedly enjoying another key moment of “progress” in the area of race relations. We are, in a word, “post-racial.” In Barack Obama, we have a Black President for the first time in U.S. history, and several other people of color—brothers Julian and Joaquin Castro, for example—have achieved prominent political roles. Still others, such as Oprah Winfrey, Jennifer Lopez, Beyoncé, and Melissa Harris-Perry, are global celebrities with the ability to shape public discourse and cultural practices.

And yet…

On the evening of May 17th, in New York City’s usually gay-friendly Greenwich Village neighborhood, 33-year old homophobe Elliott Morales fatally shot Mark Carson, a Black, gay 32-year old man, in the face after screaming anti-gay slurs (“faggot”) at him. Carson died en route to the hospital. When the police apprehended Morales a few blocks away from the crime scene, he boasted about the killing.

NYPD Commissioner Raymond Kelly (and others) rightfully identified Carson’s murder as a hate crime: “It’s clear that the victim here was killed only because and just because he was thought to be gay.” Kelly went on to note an increase in bias crimes in NYC this year, with 22 thus far in 2013 compared to 13 by this time in 2012. In fact, a gay couple was attacked just a few hours after protesters held a rally in memory of Carson in the nearby neighborhood of SoHo.

NYPD Commissioner Raymond Kelly (and others) rightfully identified Carson’s murder as a hate crime: “It’s clear that the victim here was killed only because and just because he was thought to be gay.” Kelly went on to note an increase in bias crimes in NYC this year, with 22 thus far in 2013 compared to 13 by this time in 2012. In fact, a gay couple was attacked just a few hours after protesters held a rally in memory of Carson in the nearby neighborhood of SoHo.

Across the country in Arizona, racial hate crimes increased almost 40% in Phoenix from 2009 to 2010, during a period when restrictive anti-immigration legislation, Arizona Senate Bill 1070, was being debated and ultimately signed into law. Referring to similar crimes in California—including one in which Latino cousins were assaulted by a group of white men and told to “run like you ran across the border”—San Francisco District Attorney George Gascon noted rising anti-Latino sentiments nationwide, a pattern borne out by FBI data.

Of course, it is not only Latinos who are targeted. In 2011, an intellectually disabled Navajo man was branded with a swastika. The words “white power” were written across the back of his neck. And earlier this year, two white men kidnapped, raped, beat, and strangled a 36-year old First Nations woman in Thunder Bay, Ontario. During the assault, the men called the woman a “dirty squaw” and told her, “You Indians deserve to lose your treaty rights.” Despite the viciousness of the assault (the men pulled the victim’s hair out of her head in clumps), the woman survived. The case is being investigated as a hate crime and a targeted reaction to the Idle No More campaign.

Hate speech, such as “dirty squaw,” targets a particular group in discriminatory ways or provokes violence. In the U.S., attempts to regulate hate speech bump up against the First Amendment and are thus often unsuccessful. Hate crimes are bias-related crimes. In 2009, President Obama signed into law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which extended previous hate crime legislation to include gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability. Through the elevation of hatred and hate speech to an act of violence, hate crimes operate as a kind of domestic terrorism–although not a type usually recognized by the U.S. national security apparatus.

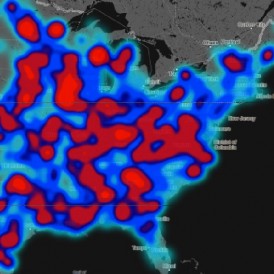

The Southern Poverty Law Center publishes statistics on hate crimes and also offers updated state-by-state information on hate groups. Visitors to the SPLC’s website can search the aptly-named “hate map” for activity in their own state. (Arizona, where one of us lives, has 28 recognized groups; and New York, where the other lives, has 38.) Researchers at Humboldt State University in California have produced another kind of “hate map,” this one tracking the incidence of hateful Tweets and their geographic location. Despite some methodological limitations of the project, the research team measured 150,000 insults across an 11-month period.

Women as a group are especially vulnerable to violence and this violence is motivated by misogyny. But violence against women is not measured in the same ways as it is for other groups. Despite the inclusion of “gender” in the Hate Crimes Prevention Act, the legislation has not been interpreted to apply to women as a group; gender is most often used in conjunction with gender identity to address transgender hate crimes, of which there are many. Nor were women as a class included in the 1990 Hate Crime Statistics Act or its reauthorization. Women also do not feature on the Humboldt State University hate map, which concentrates on insults related to homophobia, racism, and disability.

This means that domestic violence and sexual assault, while pandemic, are rarely recorded and/or prosecuted as hate crimes.

In April, Congress reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act, after intense opposition by conservatives who objected to many of the Act’s provisions, specifically those directed at protecting undocumented women and transgender women. While the law contains provisions for victims of sexual assault and domestic violence, VAWA does not conceptualize violence against women specifically as a hate crime. And in fact, some commentators suggest that hate crime legislation recognizing women as a group is unnecessary because of laws such as VAWA. Here, again, protection for women under the broader interpretation of hate crimes is limited by single-variable politics.

It is worth stating that we are not opposed to hate crime legislation, even as we understand criticisms about such policy. Indeed, we recognize the need for protections for those who are victims of crimes motivated by bias. But both hate crimes legislation and policies like VAWA ignore how neoliberalism helps to create the conditions for hate crimes, officially defined and otherwise, to occur.

It is worth stating that we are not opposed to hate crime legislation, even as we understand criticisms about such policy. Indeed, we recognize the need for protections for those who are victims of crimes motivated by bias. But both hate crimes legislation and policies like VAWA ignore how neoliberalism helps to create the conditions for hate crimes, officially defined and otherwise, to occur.

In a 1999 essay published in the Monthly Review, communications scholar Robert McChesney described the ways that democracy functions under neoliberalism. He offered the following admonishment:

“…democracy requires that people feel a connection to their fellow citizens, and that this connection manifests itself through a variety of nonmarket organizations and institutions.”

But how can democracy (here, we mean democracy with a small “d”) and engagements with others flourish when our present moment is saturated with various forms of disconnection and, more perniciously, violent connection?

Hate crimes occur within what McChesney termed a “neoliberal democracy.” He notes that within neoliberal democracy, interpersonal connection is destroyed:

“Instead of citizens, [neoliberal democracy] produces consumers. Instead of communities, it produces shopping malls. The net result is an atomized society of disengaged individuals who feel demoralized and socially powerless” (p. v).

The subsequent effects of neoliberalism within democracy are an increased sense of individualism and the lust for socio-political and economic power–the very elements that foster prejudice, discord, and acts of hate.

Beyond the social separations that we might experience within our various communities, there exist other, more tacit forms of disconnection that establish additional conditions for hate crimes under neoliberalism. These include: the maintenance of singular-variable politics as opposed to intersectional political frameworks; support of special interest causes without any engagement with the groups around which causes are organized; the commodification of “the good” for purposes of increased capital without any real desire to produce actual good in the world; and myriad forms of ideological disconnection that further the distance between our politics and practices as well as bodies within various communities.

We offer as an example the experience that one of us had while participating in a rally in Greenwich Village held in memory of Mark Carson to illuminate the insidious nature of social and ideological disconnection within neoliberal democracy:

When I started walking along the rally’s perimeters, a black adult male was walking on the sidewalk screaming profanities. He was angry at the sight of several hundred mostly white LGBTQ people walking down the street. As the crowd walked, he yelled, “All of this is your fucking fault!” About forty minutes later, after having stood through a moving moment of communal protest, people started to load a makeshift memorial with flowers, posters, pictures and other types of memorabilia. One of the signs placed at the memorial identified Mark Carson as a “gay angel.” The black man’s response might signal the fact that he failed to image Mark Carson as a gay man and, therefore, representative of the group who marched along the streets. And the “gay angel” sign, which was placed in the same spot that Mark was shot, might evidence the fact that the crowd of mostly white queer and trans protesters might have failed to image Mark Carson as a black man.

In both instances highlighted above, the responses of the black man and the mostly white crowd of LGBT folk were organized by single-identity politics. There was no connection between Carson’s sexual and racial identities at the rally, which in many ways mirrors the disconnection that often exists between queer and racial justice movements. And this type of disconnection makes sense when hate crime legislation, like the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, tends to be conceived only through the lens of singular variable politics.

In other words, even though legislation attempts to bring hate crimes based on sexual orientation and race into conversation (while eliding violence against women, specifically), progressive politics, itself a struggle for some notion of “the good,” is imbued with vectors of neoliberalism and as such tends to be disjointed and commodified. One only need to consider the increasingly popular adage adorning media reports and t-shirts, “gay is the new black,” as evidence of neoliberalism’s impact on the bastardization of historical memory regarding civil rights and the commodification of movement building.

In other words, even though legislation attempts to bring hate crimes based on sexual orientation and race into conversation (while eliding violence against women, specifically), progressive politics, itself a struggle for some notion of “the good,” is imbued with vectors of neoliberalism and as such tends to be disjointed and commodified. One only need to consider the increasingly popular adage adorning media reports and t-shirts, “gay is the new black,” as evidence of neoliberalism’s impact on the bastardization of historical memory regarding civil rights and the commodification of movement building.

With respect to the Carson shooting, some have posited the violence as a backlash against LGBTQ gains, such as gay marriage. And racially-motivated crimes in post-SB 1070 Arizona suggest that the legislation provides a kind of “permission effect” for people to move their hate from speech to an act of violence. These examples serve to highlight the kinds of disconnections and complexities rampant in neoliberal times and States. With one hand, the State may create and enforce hate crime legislation, while with the other, it might institute xenophobic anti-immigration legislation that creates the very conditions under which hate crimes might flourish.

Given the gaps that exist within hate crime legislation and myopic interpretations of single-variable hate crimes, it is important to consider what hate crime legislation and protections might look like if law proceeded in an intersectional way. As Sumi Cho, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, and Leslie McCall write in the current issue of Signs, in a special issue focused on intersectionality studies:

“Intersectionality was introduced in the late 1980s as a heuristic term to focus attention on the vexed dynamics of difference and the solidarities of sameness in the context of antidiscrimination and social movement politics. It exposed how single-axis thinking undermines legal thinking, disciplinary knowledge production, and struggles for social justice.”

What would it look like to understand hate crimes through a politics and praxis of intersectionality, such that anti-LGBT, anti-Latino, anti-disabled, anti-black, anti-First Nations, anti-women, and other prejudicial, antagonistic actions might be evidenced as interrelated effects of a fundamentally anti-community and anti-democracy moment? Hate crimes are not “one off” incidents of hateful individuals only, but rather enactments of systemic inequities and social meanings of value and worth.

Until we are able to assess hate and its various, complex manifestations in the lives of victims, democratic progress will remain a myth, no matter how many gay people marry or how many Black politicians are elected. Indeed, intersectional politics and praxis, as scholars argue in the special issue of Signs, is, at its core, antagonistic to the very act of disconnection. But perhaps more importantly, intersectionality is a framework responsive to the non-progressive operations of our neoliberal democracy. Intersectionality can and perhaps should shape the ways we read and respond to hate in these troubled times.

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

4 Comments