An Introduction to TFW's Forum on Assata Shakur: America's Grammar Book on Black Women and Terrorism

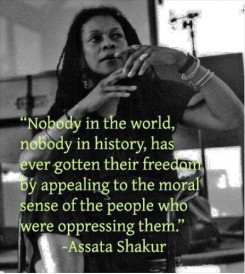

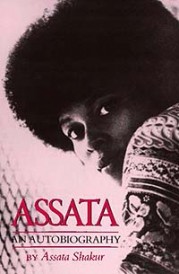

Assata Shakur has been given many names over the past four decades. Her political allies in the 1970s struggle for black liberation knew her as a comrade and freedom fighter. Ever since her escape from a New Jersey prison and exile in Cuba, she’s become an icon to many on the radical left. Some, mostly critics, still call her by her birth name, Joanne Chesimard. Now the Federal Bureau of Investigation has a new name for her: terrorist.~Jamilah King (Source)

In her brilliant and celebrated essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Hortense Spillers, black feminist extraordinaire and The Feminist Wire co-founder, lamented,

Let’s face it. I am a marked woman, but not everybody knows my name. “Peaches” and “Brown Sugar,” “Sapphire” and “Earth Mother,” “Aunty,” “Granny,” God’s “Holy Fool,” A “Miss Ebony First,” or “Black Woman at the Podium”: I describe a locus of confounded identities, a meeting ground of investments and privations in the national treasury of rhetorical wealth. My country needs me, and if I were not here, I would have to be invented.

On May 2, 2013, many of us witnessed in horror as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the New Jersey State Police declared Assata Shakur the 46th person and the first woman to be added to the agency’s list of Most Wanted Terrorists.

On May 2, 2013, many of us witnessed in horror as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the New Jersey State Police declared Assata Shakur the 46th person and the first woman to be added to the agency’s list of Most Wanted Terrorists.

A terrorist?

One who deploys terror and intimidation in the pursuit of political aims, thus causing extreme fear?

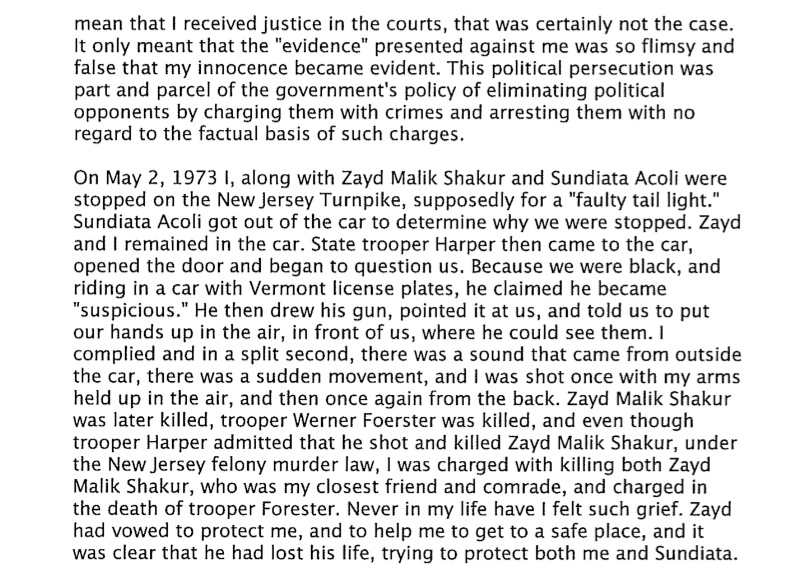

Shakur was convicted of first-degree murder of police officer Werner Forester, after a shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1973—a crime many have vehemently argued was impossible—and a crime for which Shakur has maintained her innocence. To be sure, it shouldn’t be difficult to imagine the possibility of corruption within the U.S. justice system. As a result of her conviction, Shakur was sentenced to life in prison. However, she escaped on November 2, 1979 and currently resides in Cuba under political exile.

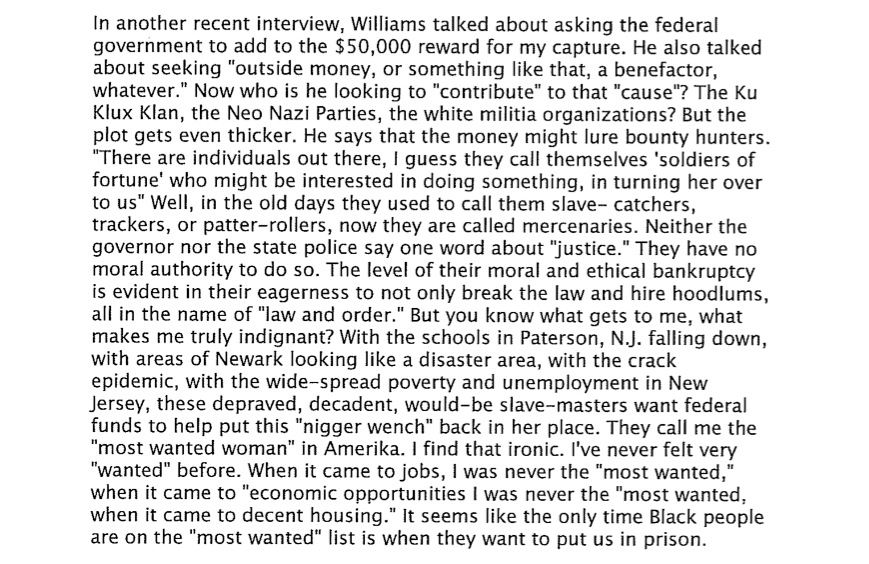

Shakur has long been a marked woman. And now she stands as a “Miss Ebony First” for the FBI. But what is her name? It certainly isn’t “terrorist.” However, today, she is “Most Wanted.” What about Shakur causes such fear and trembling? And why does America seem to need her at this moment in time? Is it because the latest terrorists had white skin? Is it to bring social, cultural and political meaning back into balance where, as Frantz Fanon once posited, the black is the symbol of evil? Did the Boston bombers disrupt our “national treasury” of rhetorical racial plenitude? Is Shakur being marked with terrorism to once again center America’s civilized/primitive dialectic or lies about its colonial mission? Is it to at once put in check youthful revolutionaries whose activist work might in fact lead to social, cultural or political change, as Angela Y. Davis recently suggested? Is it an attempt to reimagine every political prisoner in the United States as an evil terrorist straightaway? Or, is this a joint venture to hypothesize international crisis with Cuba as the target? Is it all of the above?

Shakur has long been a marked woman. And now she stands as a “Miss Ebony First” for the FBI. But what is her name? It certainly isn’t “terrorist.” However, today, she is “Most Wanted.” What about Shakur causes such fear and trembling? And why does America seem to need her at this moment in time? Is it because the latest terrorists had white skin? Is it to bring social, cultural and political meaning back into balance where, as Frantz Fanon once posited, the black is the symbol of evil? Did the Boston bombers disrupt our “national treasury” of rhetorical racial plenitude? Is Shakur being marked with terrorism to once again center America’s civilized/primitive dialectic or lies about its colonial mission? Is it to at once put in check youthful revolutionaries whose activist work might in fact lead to social, cultural or political change, as Angela Y. Davis recently suggested? Is it an attempt to reimagine every political prisoner in the United States as an evil terrorist straightaway? Or, is this a joint venture to hypothesize international crisis with Cuba as the target? Is it all of the above?

Clearly America needs Shakur at this point in history. The question on my mind is why? Why now? Why ever? According to State Police reports, there was no gunpowder residue on her hands at the time of her arrest. Alice Walker writes,

The first time I met Assata Shakur we talked for a long time. We were in Havana, where I had gone with a delegation to offer humanitarian aid during Cuba’s “special period” of hunger and despair, and I’d wanted to hear her side of the story from her. She described the incident with the New Jersey Highway Patrol, and assured me she was shot up so badly that even if she’d wanted to, she would not have been able to fire a gun. Though shot in the back (with her arms raised), she managed to live through two years of solitary confinement, in a men’s prison, chained to her bed. (Source)

“A men’s prison.” Who exactly is the terrorist here? Ain’t she a woman? Among the thousands of questions swirling in our heads, we must ask ourselves, what was the intent of violating her in this way? Was it to underscore Shakur’s simultaneous hyper-visibility and invisibility? Patriarchal right? Was it to locate her among her de-gendered ancestors, to dis-establish any semblance of personhood, or to wreak complete havoc on Shakur’s life via male-centered sexual rites? Firmly situated in the mythemes of America’s Grammar Book on race, class and gender, and thus simultaneously terrorism, Shakur is what Spillers posits as displaced captive flesh; a black woman in exile whose projected meaning rotates between tyranny and intrigue, animalization and super-humanity, and grotesquery and curiosity. She is America’s most wanted exotic “other”– cut off from the New World, yet readily welcomed “home” with her head on a platter. Is this what bell hooks meant by “Eating the Other”?

“A men’s prison.” Who exactly is the terrorist here? Ain’t she a woman? Among the thousands of questions swirling in our heads, we must ask ourselves, what was the intent of violating her in this way? Was it to underscore Shakur’s simultaneous hyper-visibility and invisibility? Patriarchal right? Was it to locate her among her de-gendered ancestors, to dis-establish any semblance of personhood, or to wreak complete havoc on Shakur’s life via male-centered sexual rites? Firmly situated in the mythemes of America’s Grammar Book on race, class and gender, and thus simultaneously terrorism, Shakur is what Spillers posits as displaced captive flesh; a black woman in exile whose projected meaning rotates between tyranny and intrigue, animalization and super-humanity, and grotesquery and curiosity. She is America’s most wanted exotic “other”– cut off from the New World, yet readily welcomed “home” with her head on a platter. Is this what bell hooks meant by “Eating the Other”?

Join us over the next two days as we attempt to “change the letter” on Assata Shakur (special thanks to my sister/comrade Aishah Shahidah Simmons, for igniting this fire). “Changing the Letter,” taken from Spillers’ essay, “Changing the Letter: The Yokes, the Jokes of Discourse, or, Mrs. Stowe, Mr. Reed,” and my subsequent work on the same, intentionally aims to interrogate, rethink, and re-appropriate meaning—meanings, which are not only carried through both the human psyche and material culture where they are brought to life and realigned again and again through a web of relations, but are also strategic and political (note the language on the image above).

Join us over the next two days as we attempt to “change the letter” on Assata Shakur (special thanks to my sister/comrade Aishah Shahidah Simmons, for igniting this fire). “Changing the Letter,” taken from Spillers’ essay, “Changing the Letter: The Yokes, the Jokes of Discourse, or, Mrs. Stowe, Mr. Reed,” and my subsequent work on the same, intentionally aims to interrogate, rethink, and re-appropriate meaning—meanings, which are not only carried through both the human psyche and material culture where they are brought to life and realigned again and again through a web of relations, but are also strategic and political (note the language on the image above).

Our hope is to both reconfigure and expose the current circulating properties and habits of language with regard not only to Shakur, but also to the ongoing criminalization of black bodies and black radicalism, which function by way of mass-mediated representation — to include the linguistic, discursive and visual — in an effort to construct and institutionalize white purity, civilization and heroicism, on one hand, and black barbarity, villainess, illegitimacy and delinquency, on the other. We do this not only for Assata Shakur but for ourselves, for we understand that circulating racial ideologies most often transform into material fury, and depending on who’s doing the terrorizing and who’s being terrorized, that fury might be seen as innocuous.

Over the next two days we’ll bring you exclusive essays for The Feminist Wire by Angela Y. Davis and Lisa Brock and Beth E. Richie, poetry by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, a love note by Heidi Renee Lewis, and related press releases (not exclusive to TFW). If interested in other works on Shakur, we encourage you to visit the following links:

- Angela Davis and Assata Shakur’s Lawyer Denounce FBI’s Adding of Exiled Activist to Terrorists List

- FBI Most Wanted Terrorists List: Who Is Assata Shakur?

- Assata Shakur 40 Years On

- Assata Shakur is not a Terrorist

- Corned Beef and Cabbage, Shrimp and Crabs: For Assata Shakur

- Sister Assata: This Is What American History Looks Like

- Assata Shakur and a Brief History on the FBI’s Most Wanted Lists

- Washington’s Most Wanted Terrorist List: Why Assata? Why Now?

- Congresswoman Maxine Waters’ Letter to President Fidel Castro on Assata Shakur (1998)

- If interested in teaching about Assata Shakur, visit Teach-Ins: Assata Shakur

- Assata Shakur

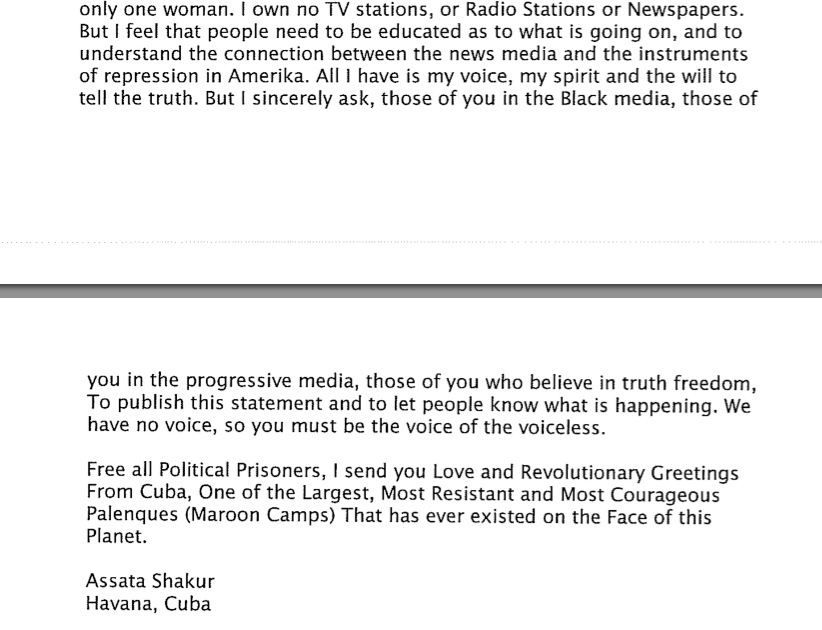

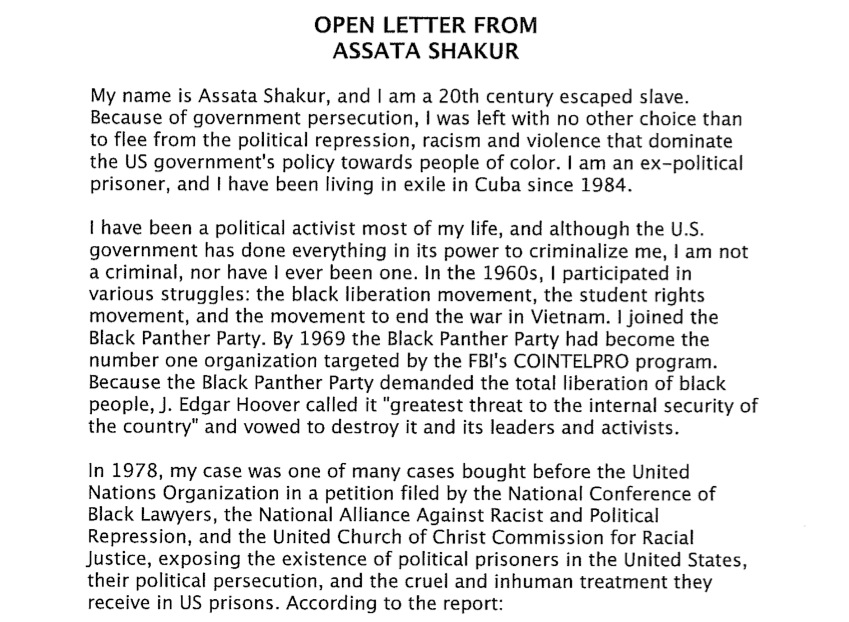

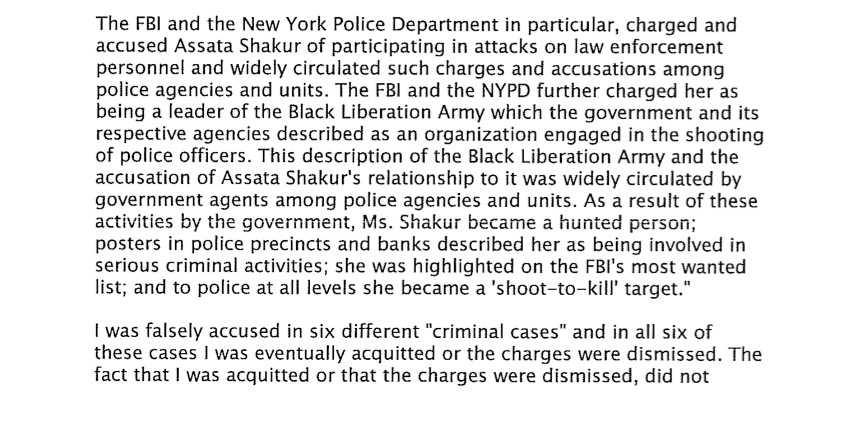

I hope you’ll join us. For now, I leave you with Shakur’s words, reprinted from the Digital Repository at the University of Texas Libraries.

4 Comments