I’m Complicated, Just like Feminisms: A Black and White Feminist Working It Out (Part II)

By Heidi R. Lewis on April 29, 2013On Friday, April 26, TFW published Part I of a conversation between myself and Dr. Connie Ruzich about all things feminism, race, socioeconomic status, religion, and age, just to name a few! Connie and I contributed our conversation to the Race & Feminisms forum, because we believe it models just one of the many ways in which feminists across various backgrounds and ideals can appreciate and reconcile their differences in an effort to affect change. This, dear readers, is Part II. Enjoy!

CONNIE: I think that there’s a less open climate for these kinds of discussions now than there was when you were a student in my class (how long ago was that??!). Blame political correctness, cowardice, widening divides in the culture itself — for whatever reasons, a lot of people (myself included) are less willing to take up trying to understand and engage with others.

HEIDI: First, I was last in your class ten years ago. Haha! But, I do realize that there’s always strong backlash against feminism, but I’m seeing something different in my classes. Now, my students are mostly white and mostly affluent—a lot have more stamps in their passports than I do—and that definitely has an impact on my teaching. They’ve seen and experienced things that the average college student hasn’t. Because of that, at least in part, my students definitely know that something isn’t quite right; they often just don’t know what it is or how to articulate what they’re experiencing, seeing, and/or hearing. Additionally, students come to a place like Colorado College expecting to receive a liberal arts education that teaches them things they maybe wouldn’t have the opportunity to learn at other kinds of institutions. I do find that my students are still a bit resistant to some of the theories they learn in my classes, though. During my critical whiteness studies class, one frustrated student said something like, “I’m just not ready to give up on objectivity!” I wasn’t asking him to do that, but when I began to challenge objectivity, that’s what he heard. That’s how deeply embedded some of our core values are—it’s difficult for us to even begin to think in different ways. However, I can say that what that particularly student was ready to do was take my class in the first place and read, think, and discuss the issues at hand. That’s saying something, and I just try my best to work with that.

CONNIE: As an example, I’m not even sure any more who will get angry if I say “black” vs. “African American.” And the other night on your Facebook wall, I felt really Out There — as in going to a potentially dangerous place (the wall discussion on Native Americans and all). Because I didn’t know your friends and I don’t know the background of your relationships, I don’t have the context — and that stuff is important. So I like your Kumbaya moment, but I think it’s actually very difficult nowadays to do what I so naively did back then – that is, as a white woman with little to no cultural experience to propose and teach an African-American literature course. Part of the change lie in the fact that ten years ago, African American literature courses were new at small, conservation, white universities like the ones I teach at – and that is no longer the case.

HEIDI: There’s something to be said about you feeling that things are difficult and still stepping out on the ledge. My students often say similar things like, “It’s so hard to know what to say or do not to offend people!” My response to them is usually a resounding, “So what?” We have to learn to embrace those difficulties and move forward. I tell them, “The acceptance rate for Colorado College is less than 30%, but you still applied. You applied because you really wanted to come here, regardless of how difficult it would be for you to get accepted.” That’s how I feel about overcoming the difficulties I face confronting my own privileges, especially my heterosexual privilege. Still, I care so much about the LGBTQ community that I face the difficulties head on, knowing full well that I’ll learn from some overwhelming mistakes along the way. That probably sounds utopian, but for me, there is no other choice. I just remind myself that nothing I experience overcoming privilege is as difficult as being marginalized.

CONNIE: Know what else I find unexpected in comparing our responses? I was a lot angrier as an early feminist than you! Now come on — you are either working against stereotypes here or lying through your teeth. You KNOW all black women are supposed to be REALLY angry!

Audre Lorde

HEIDI: Let you tell it! Haha! I bet a lot of people would argue the exact opposite about me. The other day, one of my Facebook associates told me I give off a “vibe” that was off-putting. So, I guess it just depends on the person I’m dealing with, the matter we’re discussing, and how well they do or don’t know me. I honestly don’t give a single damn about stereotypes about black women as far as attempting to dispel them. I’ve been thinking about that for a long time and writing about it a lot since late last summer. When my non-academic friends or family see me in academic settings, they’re sometimes surprised that I act and speak practically the same way I do in other environments. I won’t deny that I code-switch at times, but the older I get, the less I find that to be an effective strategy. I don’t want to be locked into being someone I’m not. However, I do recognize that I’m complicated, just like feminism. Sometimes, I’m sugary sweet and super nice. Other times, I’m downright mean and impatient. Most of the time, I’m somewhere in between. There are certain characteristics about myself that I just don’t like, though. For example, sometimes I think I’m sugary sweet when I shouldn’t be or that I’m mean and impatient when I shouldn’t be. But in the name of feminism, I work on changing those things because I don’t like those things, not because the politics of respectability suggest that I act a certain way so as not to embarrass black women everywhere. I remember reading Audre Lorde’s “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” for the first time, and it ROCKED my WORLD! That article was published the year I was born, 1981, yet it was still relevant for me the first time I read it when I was probably 21 or 22. It is now, and quite frankly, I think it will be relevant until the end of time.

CONNIE: YES to your entire comment. Yes to “I do recognize that I’m complicated, just like feminism.” In fact, a shorter version of this may make for an interesting title? I think that as women, we tend to want to simplify ourselves — to be all sugary or all angry — to fight against charges that we are overly changeable or emotional. And if there is ONE THING I’d like more people to hear about feminism, it’s that you can’t stereotype a feminist! All too often, from Hollywood to Liimbaugh, feminists are overly simplified to the point of caricature, whether for good or bad. People, it’s complicated.

I am interested in the ways in which the politics of respectability are different for me from the “politics of politeness.” That sounds odd — so let me try to explain. Sometimes, there are conventions we follow that don’t make us fake, but that instead extend dignity and respect to others. Sometimes, it is the right thing to do to pause and not just blast with every random thought that flits through one’s brain (I say this as it’s something I struggle with as a blaster). And all of this is connected to that idea I was mentioning earlier of listening and extending respect to those with whom we violently disagree. Oh dear. I seem to have gone all Kumbaya again.

HEIDI: I was actually hoping you’d want to talk about this. I’m thinking about the “cult of domesticity” (or “the cult of true womanhood”) that dictated white women’s behaviors in the 19th century. I’ve written previously about Darlene Clark Hine’s “culture of dissemblance” theory, which examines “the ways black women police our own bodies in attempts to self-protect against [people in power].” So, that’s ultimately what I think is the biggest difference. The “politics of respectability” is inextricably linked to race and racism. It is the way that black people attempt to protect themselves from the brute, violent forces of racism. There were actually manuals instructing black people about how to act in public spaces so that they wouldn’t be mistreated or even killed.

CONNIE: Interesting further thoughts on the politics of respectability: could we play with this idea and say that black women have been silenced through pressures to be respectable, while white women have been silenced through pressures to be polite? And these pressures have been internalized? For some reason, I keep thinking that the term “double consciousness” (DuBois) and contrary instincts (Alice Walker) are relevant here.

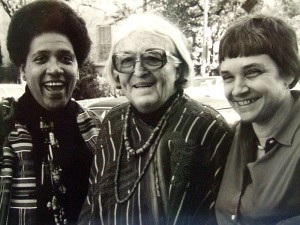

Audre Lorde, Meridel Le Sueur, and Adrienne Rich (1980)

And lastly, YES to anger. And to embracing anger. A few months ago, I facebook posted to you my favorite thing on anger — I think it was Adrienne Rich’s essay, “When We Dead Awaken.” Here’s part of Rich’s essay that seems relevant:

In rereading Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own for the first time in some years, I was astonished at the sense of effort, of pains taken, of dogged tentativeness, in the tone of that essay. And I recognized that tone. I had heard it often enough, in myself and in other women. It is the tone of a woman almost in touch with her anger, who is determined not to appear angry, who is willing herself to be calm, detached, and even charming in a roomful of men where things have been said which are attacks on her very integrity. Virginia Woolf is addressing an audience of women, but she is acutely conscious–as she always was–of being overheard by men: by Morgan and Lytton and Maynard Keynes and for that matter by her father, Leslie Stephen. She drew the language out into an exacerbated thread in her determination to have her own sensibility yet protect it from those masculine presences. Only at rare moments in that essay do you hear the passion in her voice; she was trying to sound as cool as Jane Austen, as Olympian as Shakespeare, because that is the way the men of the culture thought a writer should sound.

HEIDI: Every time I read or hear a reference to Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own,” I can’t help but think about Gertrude Bustill Mossell’s “A Lofty Study,” written almost 50 years before. Of course she was pushed to the margins until being recovered by black feminist writers. But to your point, that is something that I will forever love and appreciate about the so-called “second wave” of feminist theory and activism. These women reminded us that it was okay, and sometimes healthy, to be angry. It’s not surprising that people still find ways to subjugate women’s anger today. While I agree with bell hooks that silence can be a form of resistance, I fight every day to not be silenced by oppression.

CONNIE: I remember reading a novel that made the point that (white) women have access to a kind of humor that (white) men don’t (white was presumed in this case). Because we don’t run the world, we can make fun of those who do. And (white) men can’t do that.

HEIDI: I think that marginalized people have found comedy to be just one strategy for coping with a world that hates them, frankly. I’m actually developing a course that examines the ways in which comedy and humor are theoretical, especially regarding race, gender, and sexuality. Of course, I’m thinking about contemporary comics like Margaret Cho, Wanda Sykes, Chris Rock, and Louis C. K. but also classic comedians like Richard Pryor, George Carlin, and Phyllis Diller. In “What Kinds of Times Are These,” Rich writes, “This isn’t a Russian poem. This is not somewhere else, but here—our country, moving closer to its own truth and dread, its own ways of making people disappear.” I think comedy is just one way that marginalized people sustain their voice and resist being disappeared.

CONNIE: I’ve said to my daughters, it’s an interesting thing to have family members (or husbands) who are poles apart from you with regard to political values — and the kinds of values we’re discussing. For me, it’s being married to a man who is deeply politically conservative. I oppose some of the political views he embraces — and yet I love him and know him to be a caring, thoughtful person who supports me and my right to my own values. In a similar way, my parents, my in-laws, and my siblings don’t share my feminist perspectives — and in fact, reject them. That’s like what you were talking about with your Nana. I don’t mean to go all PollyAnnish on you, but for me, an important piece of my feminism is trying to explain and defend my values to those who are hugely opposed, violently antagonistic to those views– and yet to continue to love one another. And that means I have to listen to them too. OK, enough of the Kumbaya moments.

HEIDI: My own practices in that regard have admittedly changed quite a bit over the years, especially since I became a professor of feminist and gender studies a few years ago. Now, I’m having conversations about feminism with young and naïve students all of the time. In addition to that, I’m having similar conversations with colleagues, within and outside of my institution. I’m writing articles about it, presenting conference papers about it, and so on. In addition to that, sometimes I feel like the feminist go-to person in my family and circle of friends. You can’t imagine how much people post things on my Facebook wall or send me tweets and emails asking for my feminist opinion. It gets downright exhausting. I’ve learned from my black feminist foremothers that self-care is an especially important aspect of being a feminist, something that we don’t talk about as often as we should. I actually started teaching Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters (1980) in my black feminist thought class in order to remind myself and my students about the importance of mental, spiritual, intellectual, and emotional health. That said, sometimes I deliberately choose not to defend my values to those who are opposed to feminism, violently and antagonistically or otherwise. Sometimes, I have to protect myself and my time as much as humanly possible, or I fear I may wind up just like the main character in The Salt Eaters, Velma, in a mental hospital fighting for my life.

CONNIE: And I have seen too much lately of women putting down other women’s “Brand” of feminism, without carefully thinking about the communities from which those women speak. For example, I really don’t care at all for Sarah Palin as a politician (and I can’t say much about her as a person, as I don’t know the woman, though she has made what look like some strange and crazy choices and comments). Still, I think it’s important to listen to conservative women and their comments on feminism — as outlandish as they may seem. I’ll bet you and I have eye-rolled our Nanas and family members — but we’ve listened.

HEIDI: This is why I try to always remind myself to pluralize feminism. It’s really feminisms. Some of them work well. Some of them don’t. All of them, as you mention, must be contextualized. The theories must serve the people for and about whom they are written. The paradigms developed in order to affect change must do the same. This is why I love writing for The Feminist Wire, because it allows me to continue having these conversations with people, academics or otherwise, in ways that are productive and healthy. That’s why I was really excited about this forum, because I knew it would be a place where we could all nurture and participate in these conversations, sharing them with people across the world.

Heidi R. Lewis is an Assistant Professor of Feminist & Gender Studies at Colorado College. Her teaching and research focus on feminist theory, gender and sexuality, Black Studies, Critical Media Studies, Critical Race Theory, Critical Whiteness Studies, social justice, and activism. Her essay “An Examination of the Kanye West’s Higher Education Trilogy” is featured in The Cultural Impact of Kanye West, and her article “Let Me Just Taste You: Li’l Wayne and Rap’s Politics of Cunnlingus” is forthcoming in the Journal of Popular Culture. She is currently in the process of completing articles that examine Rihanna’s “Pour It Up,” as well as FX’s The Shield. She has given talks at Kim Bevill’s Gender and the Brain Conference, the Frauenkreise Projekt in Berlin, the Educating Children of Color Summit, the Sankofa Lecture Series, the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, the Gender and Media Spring Convocation at Ohio University, and the Conference for Pre-Tenure Women at Purdue University, where she earned a Ph.D. in American Studies (2011) and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies (2008). Heidi has also been a contributor to Mark Anthony Neal’s NewBlackMan, NPR’s “Here and Now,” KOAA news in Colorado Springs, and KRCC radio (the Southeastern Colorado NPR affiliate), and she was featured as a Racialicious “Crush of the Week.” She and her husband, Antonio, live in Colorado Springs with their two children, AJ and Chase, and their cat Max. Learn more by following Heidi on Twitter at @therealphdmommy and by visiting her FemGeniuses website.

Heidi R. Lewis is an Assistant Professor of Feminist & Gender Studies at Colorado College. Her teaching and research focus on feminist theory, gender and sexuality, Black Studies, Critical Media Studies, Critical Race Theory, Critical Whiteness Studies, social justice, and activism. Her essay “An Examination of the Kanye West’s Higher Education Trilogy” is featured in The Cultural Impact of Kanye West, and her article “Let Me Just Taste You: Li’l Wayne and Rap’s Politics of Cunnlingus” is forthcoming in the Journal of Popular Culture. She is currently in the process of completing articles that examine Rihanna’s “Pour It Up,” as well as FX’s The Shield. She has given talks at Kim Bevill’s Gender and the Brain Conference, the Frauenkreise Projekt in Berlin, the Educating Children of Color Summit, the Sankofa Lecture Series, the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement, the Gender and Media Spring Convocation at Ohio University, and the Conference for Pre-Tenure Women at Purdue University, where she earned a Ph.D. in American Studies (2011) and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies (2008). Heidi has also been a contributor to Mark Anthony Neal’s NewBlackMan, NPR’s “Here and Now,” KOAA news in Colorado Springs, and KRCC radio (the Southeastern Colorado NPR affiliate), and she was featured as a Racialicious “Crush of the Week.” She and her husband, Antonio, live in Colorado Springs with their two children, AJ and Chase, and their cat Max. Learn more by following Heidi on Twitter at @therealphdmommy and by visiting her FemGeniuses website.

Connie Ruzich is a University Professor of English at Robert Morris University, where she teaches linguistics, literature, and education courses. She earned a Ph.D. in Writing at the University of Pennsylvania and a Masters in Literature with a concentration in Composition and Rhetoric at the University of Pittsburgh. Her research examines the various ways in which language use and practices shape identities, from white students’ resistance to the study of multicultural literature to Starbucks’ appeals to the language of love in their corporate advertising. She is currently working on a scholarly examination of dialect in Stockett’s novel The Help.

You may also like...

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

0 comments