Feminist in My Kitchen

By Nilofar Ansher

The Romantic Tedium of Cooking

Our notions of love and nurture are bound with the flavor, texture and warmth of food cooked and served by our mothers. It’s the leitmotif of my childhood in the late 1980s: the children busy with homework and heading off to school, dad reading the newspaper and hurrying off to work, and mom marking her presence in each room – the bedroom for dressing us up, the kitchen to cook and pack our tiffins, the hall to send us off – with the main door threshold marking the limits of mom’s influence.

This has been a constant in most Indian homes. The daily pattern of women tending to the household and the men heading out is a typical middle-class phenomenon and has been projected as part of the narrative of an Indian women’s grihasti. It presupposes a division of labor: husbands handle livelihoods, while wives nurture lives. You won’t find a single imprint of this domestic structure in the homes of the lower middle class or poor families. There, women head out along with their husbands to earn a living, as daily wage laborers or workers in small factories and cottage industries. But cooking remains a woman’s fixture, no matter which class society imprisons you within.

The measure of our worth was also calculated by the day’s menu – the more special the dish, the more mom loved us. And Sundays were reserved for an extra helping of her boundless love, as witnessed by the biryanis, ghee rice, fried accompaniments, and dessert. Days when ordinary meals were served meant mom didn’t love us enough to take an effort to cook our favorite items. Simplistic? Yes. But that’s a child’s way of making sense of the ritual of cooking and associating tasty food with love. We connect the dots – rather incorrectly – equating the action (cooking) with intention (love).

Even though we lived next door to a household where an aunty worked at a bank, she was still expected to finish the cooking, supervise the maid, pack the tiffins for her children, do the same for herself and her husband, get ready, and then rush to catch the 9 am bus. What sets my family apart from her and other neighbors and relatives is that my father is an able cook himself and helped mom with kitchen work whenever he could, in the morning and after returning home from office. My brother and I were never asked to help with even the simplest of chores, like washing or peeling vegetables, or preparing tea, and we took it for granted that cooking is a woman’s domain with occasional assistance provided by men. My assertive, outspoken, and opinionated mother never highlighted that father helping out in the kitchen was an uncommon practice and as a girl, I grew up with the notion that while cooking would be my lot, I would be ably supported by my partner when I commence my marital domesticity.

Outsourcing Domesticity

On our yearly pilgrimage to the southern part of India, at my parents’ native place, I experienced another aspect of domesticity. Houses in my village are large affairs, with kitchens dominating the entire backyard and a cotery of maids, errand boys, and cooks to manage the household. Here, cooking was not strictly the domain of the women of the house; they had to supervise the cooks and manage the chores, but they were not physically responsible for shucking the peas, stirring the curries, or cleaning the entrails of the chicken. Hired cooks were not necessarily women, and on festive occasions and ceremonial functions, when vats of food had to be cooked, served, and distributed, male cooks were the obvious choice for the job.

This notion of the privileged, landed gentry in the village following a different, but familiar pattern of domesticity is echoed by an extract from Lakshmibai, a Malayalam women’s periodical published in 1908: ‘We all know that the periodical Lakshmibai is published for the particular use of women. Though there are various issues women should know that are discussed here, I have yet to see anything written on the science of cooking—something women should necessarily know…I do not think anyone will object if I say that women should have the knowledge of cooking. Like caring for one’s husband, tending one’s children and supervising the household, this too is important. I do hope that readers do not misunderstand and get ready for battle with me. The essence of what I say is not that women should, like servants, go to the kitchen and slave. I am only saying that women should know enough to ensure that their servants work as desired. It is the housewife who has the burden of ensuring the health of the husband, of the children and of herself. If she has to carry out this responsibility adequately, she has to have a decent knowledge of cooking.’ (Sharmila Sreekumar, Writing the Culinary in Early Twentieth Century Malayalam, in The Writer’s Feast, Orient BlackSwan, 2011).

It’s elementary, then, to deduce that economic status has much to do with setting domestic norms and expectations. But we know that differential financial backgrounds don’t really alter traditional gender roles – they instead shift the degrees of expectations. Take the case of American women in the post-World War II era, which saw an increase in purchasing power and consumerism. This was the time when ‘women-friendly’ electronic appliances and household gadgets flooded the markets, and blatantly positioned as a means to escape “from the shackles of household chores.”

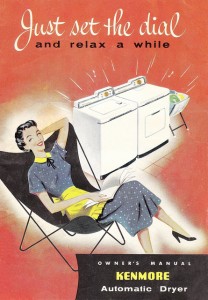

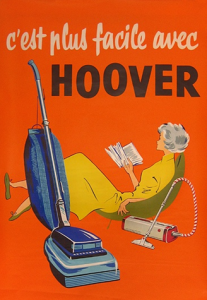

These vintage advertisements dating to the 1950s and 60s seem to suggest that technology has finally resolved the age-old conflict of who will do the dishes. With the aid of appliances, household chores could now be a relaxing activity, one to pursue in between all our reading and tea time. Women smiling cheerfully, raising their eyebrows in pride, looking over their shoulders at their husbands with a smirk, intimating the reader that they have managed to bring order to the home without breaking into a sweat.

These vintage advertisements dating to the 1950s and 60s seem to suggest that technology has finally resolved the age-old conflict of who will do the dishes. With the aid of appliances, household chores could now be a relaxing activity, one to pursue in between all our reading and tea time. Women smiling cheerfully, raising their eyebrows in pride, looking over their shoulders at their husbands with a smirk, intimating the reader that they have managed to bring order to the home without breaking into a sweat.

But the reality was much different, as expounded by Betty Friedan in her seminal work The Feminine Mystique (1963), “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night – she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question – is this all?” Friedan makes two points here: the sense of ennui experiened by American women because of their endless chores, and the dissatisfaction that arises out of being tied down solely by chores. The technology that was supposed to give women more time outside the kitchen and our homes, ended up restricting us within.

In her critique of civil engineer Samuel C. Florman’s book, Blaming Technology: the Irrational Search for Scapegoats, anarchist and feminist Wendy McElroy explains how Florman – himself a champion of engineering, modern science and technology – was forced to comment on the increasing tension between the scientific community and feminism, with somewhat bewildered amazement: “The development of household appliances, for example, instead of freeing the housewife for a richer life as advertised, has helped to reduce her to the level of a maidservant whose greatest skill is consumerism. Factory jobs have attracted women to the workplace in roles they have come to dislike. Innovations affecting the most intimate aspects of women’s lives, such as the baby bottle and birth-control devices, have been developed almost exclusively by men. Dependent upon technology, but removed from its sources and, paradoxically, enslaved by it, women may well have developed deep-seated resentments that persist even in those who consider themselves liberal.”

In her critique of civil engineer Samuel C. Florman’s book, Blaming Technology: the Irrational Search for Scapegoats, anarchist and feminist Wendy McElroy explains how Florman – himself a champion of engineering, modern science and technology – was forced to comment on the increasing tension between the scientific community and feminism, with somewhat bewildered amazement: “The development of household appliances, for example, instead of freeing the housewife for a richer life as advertised, has helped to reduce her to the level of a maidservant whose greatest skill is consumerism. Factory jobs have attracted women to the workplace in roles they have come to dislike. Innovations affecting the most intimate aspects of women’s lives, such as the baby bottle and birth-control devices, have been developed almost exclusively by men. Dependent upon technology, but removed from its sources and, paradoxically, enslaved by it, women may well have developed deep-seated resentments that persist even in those who consider themselves liberal.”

Transmute this power equation to Indian shores, and we are looking at a majority of women who don’t have access to any of the more expensive contraptions, and rely on their self-labor and domestic help to complete household and external chores. The only two options we are presented with – by the system – are 1) earn enough to buy appliances that more often than not end up burdening you with their setup, usage (and the assumption of ease) and maintenance or, 2) hire a maid and/or a cook for pittance and commence another cycle of exploitation, in this case, of women and men from a class below ours. The domestic help sector in India is informal, unorganized, and does not see the benefit of any government schemes. Maids work for roughly an hour to three hours depending upon the household, and cover five to six houses or families a day. A typical working day could last anywhere from four to 12 hours, and involves sweeping the floor, mopping, washing clothes, utensils, and additional work such as cleaning the windows, ceiling fans, buying groceries, or taking care of the baby for a couple of hours.

This is not a uniform pattern of work across all households, in fact, and few can hardly afford to hire a maid to do more than the square set of sweeping-mopping-clothes-utensils, paying them close to US$30-80 per month. In a country where close to 40% of the population lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 per day (purchasing power parity, figures by World Bank 2008), the issue of a middle-class household hiring a lower middle class or poor person for help seems fraught with economic injustice and class tensions. Outsourcing as a model of altering domestic patterns doesn’t seem to be ethical or foolproof. What do we need to to to change this equation then? Well, why can’t we count on each member of the family to chip in? Where have our “better” halves (for heterosexual women) disappeared and why haven’t we involved them in adhering to the idea of equal division of labor, be it within the kitchen or outside?

This is not a uniform pattern of work across all households, in fact, and few can hardly afford to hire a maid to do more than the square set of sweeping-mopping-clothes-utensils, paying them close to US$30-80 per month. In a country where close to 40% of the population lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 per day (purchasing power parity, figures by World Bank 2008), the issue of a middle-class household hiring a lower middle class or poor person for help seems fraught with economic injustice and class tensions. Outsourcing as a model of altering domestic patterns doesn’t seem to be ethical or foolproof. What do we need to to to change this equation then? Well, why can’t we count on each member of the family to chip in? Where have our “better” halves (for heterosexual women) disappeared and why haven’t we involved them in adhering to the idea of equal division of labor, be it within the kitchen or outside?

Setting egalitarian goals from childhood also help change the equation from ridiculing and rejecting domestic work into valuing domestic life as something that is as important as professional work outside our homes. When everyone who belongs to a household does their part of the chores, the question of placing an economic value on these tasks would also be eliminated.

Re-discovering the Kitchen

Up until I turned 22, I was not compelled to learn cooking. Understanding that academics and extra-curricular activities were more relevant to my life in college, my mother let me be. But the fact that I would have to eventually learn how to wield the iron skillet and spar with the spatula was not far away from my thoughts. And this was not something I dreaded or frowned upon. Rather, the years of reading romance novels and being fed on a diet of cookery shows on television and Hindi movies filled me with the romantic notion of cooking for my husband. Fiction and popular culture drive home the point that it doesn’t take too much to win the love and appreciation of a husband and his family, which required only that we learn to navigate their circuitous intestines! Love, affection and being a dutiful daughter-in-law are consistently associated with being a good cook. The ritual of the pehli rasoi in Hindu households, where the newly-married girl is supposed to cook a dessert and offer it as sacrifice to the goddess, followed by cooking a variety of dishes that cater to the ten-member family’s tastes, is captured in fuzzy, warm tones of delight in our soap operas.

Plump with this diet, I approached my own domestic life on a Dopamine overdose of enthusiasm and determination. My husband’s praise was the prize, and the race involved multiple tasks: prepare meals on time, plan menus with variety, serve dishes in style, keep the kitchen clean, don’t complain about the effort it took, and lastly, don’t appear too eager for praise. I agree, this soap opera kept me satisfied and lulled for a few months, until I acquired a full-time job. Now, the goal was not just to manage the home, but also external chores and the demands of a multi-national schedule. The women in my family only encouraged me to embrace the woman in me, who was supposed to be capable of great feats of juggling. Cooking became a bone of contention: is it alright to hire a cook or do we change our eating habits and order out? Neither option seemed the best, especially since I couldn’t find a maid and second, I loved the taste of my concoctions too much to cede control to another person. With no promises forthcoming from the husband to enter the kitchen and support my labor, I realized that the odds were stacked against me. I could either spread myself thin, in a bid to prove that I could ‘have it all,’ or be honest with myself and accept the truth: the system is rigged against me – against all of us women – and it’s time to call show.

It is in patriarchy’s best interest to step on the pedal of tradition, cloak it as love, and drive women into a guilt trip. John S. Allen, in his book The Omnivorous Mind (Harvard University Press, 2012), draws up a complex story arc with food, gender and the agents of memory playing key roles, referring to the enactment of the traditional Thanksgiving meal in American homes every year: “Even with some breakdown of traditional gender roles concerning the preparation and serving of the Thanksgiving meal, it still provides opportunities to display aspects of gender…including the competitive aspect of eating displayed by men.” Sreekumar succinctly captures this anomaly in her article: “…the act of cooking and the home in which it was imagined as taking place were in fact fictions designed to support one side of the debate, ongoing in Malayali society of the time, over what exactly was the woman’s role in the house, and indeed what the categories of ‘wife’, ‘husband’ and ‘family’ ought to mean.”

Deconstructing our association of home-cooked meals with mother’s love is also a journey in ownership of domestic life, for both men and women. Domesticity in general and cooking in particular don’t have to be phenotyped by their historical gender orientation. What is required is a recalibration in how we approach tasks within the realm of our homes. For instance, can we try to deconstruct our relationship with waste: transform the disgust associated with taking out the garbage into a chore that is necessary to keep the kitchen free from germs and diseases. Language once again plays a significant role. Did you know that the word ‘menial’ has its origins in the Middle English meinial, meaning belonging to a household? So, the very idea of anything related to domesticity has been systematically constructed as pertaining to servility.

Deconstruction works by cleansing the stigma associated with all our chores – think about how we refer to cleaning the toilets as ‘disgusting’ but don’t mind our women cleaning the same. I do see the winds of change in my generation, beginning with my maid who says that in her home, her husband is in-charge of cooking “as he’s good at it and I am not.” The age-old trope of drawing parallels between woman and cooking needs to be dismantled, especially since loving one’s family has nothing to do with mastering the skills of putting together a meal.

_______________________________________________

Nilofar Ansher is a writer, editor and researcher from India. Her research interests include urban ecology, disability rights and inclusive culture, museum studies, cybersociology, cinema, folk studies, and Feminism. She has a master’s degree in Ancient Indian Civilization, History and Culture, and a bachelor of arts in history.

Nilofar Ansher is a writer, editor and researcher from India. Her research interests include urban ecology, disability rights and inclusive culture, museum studies, cybersociology, cinema, folk studies, and Feminism. She has a master’s degree in Ancient Indian Civilization, History and Culture, and a bachelor of arts in history.

Previously, she was the Community Manager for the ‘Digital Natives with a Cause?’ project, a research initiative of the Bangalore-based Centre for Internet and Society, that focused on the narrative of youth, technology, and politics from the framework of the Global South. Currently, she is a communications analyst with a not-for-profit agency that works towards ICT accessibility advocacy for persons with disabilities. She runs ‘accessibility in museums,’ a web initiative aimed at documenting the idea of cultural access for persons with disabilities.

Nilofar’s writings have been published in The Good Men Project, Bangalore Mirror, DNA India, The State, UltraViolet, PC Tech Magazine Africa, Careers360, Himachal Magazine, and Express Tribune Pakistan. For more of her work, visit http://www.longformwriter.wordpress.com, http://www.trailofpapercuts.wordpress.com and http://www.accessibilityinmuseums.wordpress.com. She tweets as @culture_curate and @accessibilityinmuseums.

4 Comments