Kill With Power

By Shaka McGlotten

“Dig Deeper!” exhorts Shaun T. He sidles up to Chris, a big, dark-skinned guy at the back of the basketball court; Chris looks like he’s floating during “power jumps,” an exercise in which you launch off the floor and, mid-air, slap your hands against your knees. Shaun T asks Chris, “Ready, brother?” and then they move into floor sprints. Next, “moving pushups.” I look over at my biceps as I struggle across the floor of my studio apartment. Are they getting bigger? I can’t tell.

My boyfriend and I usually hedge around the sorts of bodies we find attractive, tentatively vulnerable to one another, wary of what our admissions might reveal about our politics or how they might affect our sense of feeling wanted by the other. Physically, we’re similar; about 5’ 8” (although I insist I’m a little taller) and a 150 pounds. My shoulders are broader after years of swimming. His feet hairy like a hobbit’s. Neither of us is small, but we’d both be dwarfed by Chris and Shaun T. We learn about one another’s desires partially through our respective porn selections. We’re both into “all sorts,” we say, but one of us often goes for older, muscular guys and the other for younger, smoother ones. Sweating through power jumps, floor sprints, and moving push-ups, I wonder whether I’m getting buff for him or some imagined public. Regardless, the “Insanity” program has been great for both of our asses.

My boyfriend and I usually hedge around the sorts of bodies we find attractive, tentatively vulnerable to one another, wary of what our admissions might reveal about our politics or how they might affect our sense of feeling wanted by the other. Physically, we’re similar; about 5’ 8” (although I insist I’m a little taller) and a 150 pounds. My shoulders are broader after years of swimming. His feet hairy like a hobbit’s. Neither of us is small, but we’d both be dwarfed by Chris and Shaun T. We learn about one another’s desires partially through our respective porn selections. We’re both into “all sorts,” we say, but one of us often goes for older, muscular guys and the other for younger, smoother ones. Sweating through power jumps, floor sprints, and moving push-ups, I wonder whether I’m getting buff for him or some imagined public. Regardless, the “Insanity” program has been great for both of our asses.

Shaun T’s earlier fitness program, “Hip Hop Abs,” is so much gayer. He’s coy rather than butch. And he’s smaller, less built up. His voice is higher; he sounds like the supportive gay friend encouraging his girlfriends to get fit. And whereas “Insanity” insists “Get Fit or Get Out” to driving rock chords (with an occasional inspirational progression that seems derived from the Buffy theme song), “Hip Hop Abs” is softer, lite–hip hop for rhythmless white boys. Ellen fares well, too. In the “Walk and Shake,” Shaun T and crew sashay across the floor, snap their fingers, and turn on their heels, before taking their attitude to the other side of the studio: “I’m cute, and I’m working out.”

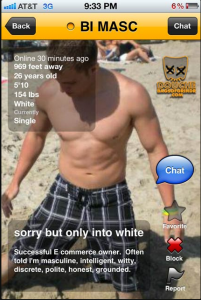

As an undergrad at Grinnell College, I hardly ever worked out. I swam occasionally, or walked around the small town when it wasn’t too cold (and it usually was). Unexpected boners in the shower embarrassed me, so I stopped going. If only I knew then what I know now about public sex. Recently, I was invited back to give a talk about the hook-up app Grindr . Mostly, though, I talked about the website douchebagsofgrindr, a name-and-shame site that posts the profiles of Grindr users with offensive text in their profiles: “no fats, no fems, no spice, no rice.”

As an undergrad at Grinnell College, I hardly ever worked out. I swam occasionally, or walked around the small town when it wasn’t too cold (and it usually was). Unexpected boners in the shower embarrassed me, so I stopped going. If only I knew then what I know now about public sex. Recently, I was invited back to give a talk about the hook-up app Grindr . Mostly, though, I talked about the website douchebagsofgrindr, a name-and-shame site that posts the profiles of Grindr users with offensive text in their profiles: “no fats, no fems, no spice, no rice.”

I performed the talk in high Manhattanite steampunk drag-tweed newsboy cap covering my shaved head, graphite, indigo, and black palette, worn but obviously expensive calf-high boots. It’s a tough look, but not too sharp-edged. One early morning I walked around the empty campus alone, clopping boots echoing in the loggia. I was overcome with nostalgia. I recalled my very different, more androgynous gender presentation sixteen years prior. I borrowed girlfriends’ clothes: bellbottoms clung to my pre-Insanity butt and legs and my skinnier arms–all jutting elbows and bony wrists-either disappeared into voluminous sweaters or were exposed in too tight T-shirts. My favorite had an iron-on print of Chewbacca and Han Solo. I often wore a yellow, bird-shaped barrette to hold back the soft curls on half of my head. Once, as I was locking up my bike outside of the grocery store downtown, a young girl stopped and stared at me, finally asking, “Are you a boy or a girl?” I was a little surprised. “A boy.” Although I was active in gay and lesbian issues on campus, it would be years before I heard the word “genderqueer.” I’ve never seen it on a cruising profile, where masculinity is ubiquitously celebrated and faggotry scorned.

In the wonderful collection Why are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots?, writers explore the complex relationships that tie masculinity and queerness together, and especially the ways the privileges attached to adhering to masculine ideals are complicit with different forms of violence — from homonationalist mainstreaming to social exclusion. In Nick Clark’s “Penis is Important For That,” he describes a progressive series of flirtatious encounters with an older gay man, Joshua that come to a sudden stop when Nick outs himself as a trans man. Joshua finds Nick attractive, but doesn’t know what that means for his identity as gay. When they meet again, he tells Nick, “[. . .] I have to tell you, this isn’t going to go any further. I’m gay, and penis is important for that.” Joshua described the process of coming to terms with himself, learning to like himself as a gay man. Dick was fundamental. Nick thinks to himself: “‘Well,’ I wanted to say, ‘I like myself too, Joshua. Stop talking about my body as though it’s the problem when you’re the one obsessed with penises.’ He kept emphasizing how much of a struggle it was for him to assert his gay identity and to become who he had become. It seemed that who he had become, though, was someone who couldn’t date a boy he was attracted to.”

A few years ago, one of my former students showed a fabulous video in class we were taking together. Kate Gilmore’s “Performance Art” was riotous, and deeply satisfying. I had taught many of the students in the class, so we knew each other, and nourished different sorts of intimacy through the semester. I struggled to produce work about failure, about not being tough or strong or good enough. One day, I lost my voice. My performance: struggling to repeat, “I don’t feel like I’m doing this right, but I want to do the best I can.” Stephen’s video inverts this image of fragile aspiration and stubborn resilience. It’s a hyperactive study in masculine ideals set to the (female fronted) Swedish death metal band Arch Enemy’s cover of Manowar’s “Kill With Power.” Men work out, fight, and drink beer. They kill with power.

Occasionally my boyfriend and I will scan the Net, looking for other people to fool around with. We debate what to include in our profiles. Kill with Power? I insist that we need to be clear about what we’re looking for. We’ve had long discussions on how to present our racial identities. Do we want to maximize our chances of hooking up or hew to our anti-racist, anti-capitalist commitments? When we met, he identified himself as “Middle Eastern,” even though his grandparents immigrated to Palestine from Eastern Europe in the 1930s. We discuss my stories about what happens when I make a point of marking my blackness online. Usually I’m rejected, unless I’m willing to play Mandingo. Others – lovers and acquaintances – are less sensitive in discussions of cruising sites and hookup apps; “no offense,” they tell me, “but you don’t look black.” I suppose this is a way of saying that these people don’t see me as a thug, as violent or criminal. Maybe it’s because I’m masculine, but not hypermasculine, like Shaun T. They can find me attractive precisely because I don’t look black. Yeah, what’s the problem?

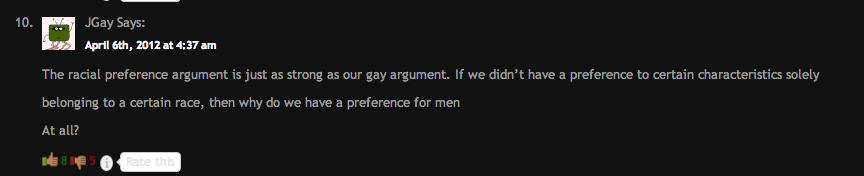

A “post-racial” America remains a fantasy. Race remains one of the structuring structures of our culture, as any close examination of folks’ intimate desires reveals. When my friends or, occasionally, students defend their racial preferences as individual rather than social, I get aggro: “the idea that you can be attracted to one group of people over another, or not attracted to a particular group, is inherently racist precisely because it homogenizes a hugely diverse array of people, reducing them to skin color, other stereotyped ideas about phenotype, or to a handful of social practices and behaviors more reflective of white supremacist fantasies and fears than any lived reality.” Sometimes, they equate racial preferences with sexual orientation, toxic fallout from the culture wars, in which sexual object choice is at once the result of biological predisposition and ahistorical, acultural individual “preferences.” “Being attracted to a particular race is like being attracted to a particular sex.” This rationalization is accompanied by an implicit, “liberal” assumption that our individual choices deserve, at least, to be tolerated without too much fuss. When this happens, I become absolutely niggerly.

Recently, my boyfriend and I went online and I noticed that the language of our profile included this: “into masc. guys.” We were embarrassed. Did we mean musc(ular) guys? Neither of us remembered writing it. We changed it to “into sexually confident guys.” Desires can change, like politics.

_____________________________________________

Shaka McGlotten is an artist and anthropologist. He is an Associate Professor of Media, Society, and the Arts at Purchase College, SUNY, where he teaches courses on ethnography, new media, and digital culture.

Shaka McGlotten is an artist and anthropologist. He is an Associate Professor of Media, Society, and the Arts at Purchase College, SUNY, where he teaches courses on ethnography, new media, and digital culture.

0 comments