Olivia Pope and the Scandal of Representation

By Brandon Maxwell

On April 5, 2012 Shonda Rhimes premiered yet another television drama that would entice millions of viewers to faithfully return to their couches weekly to watch her newest production – Scandal. In case you haven’t seen it, this drama purportedly centers on protagonist Olivia Pope (Kerry Washington), a “Professional Fixer,” and her efforts to make political problems go away. While this is the drama’s claim, a closer examination reveals that Scandal actually centers on the seemingly salvific protagonist of imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy* and the lengths to which all people – women and men, black/brown and white, gay and straight, etc. – will go to preserve it.

This should not surprise viewers. Today, very few films, plays, and TV shows take seriously the task of not only imitating life but also critiquing it, and thus turning it on its head. One might even argue that they fail to truthfully imitate life. In an essay entitled Mass Culture and the Creative Artist, James Baldwin echoes this sentiment. Critiquing a couple films of the late 1950s, he writes,

These movies are designed not to trouble, but to reassure; they do not reflect reality, they merely rearrange its elements into something we can bear. They also weaken our ability to deal with the world as it is, ourselves as we are. (Baldwin 4)

Rhimes’ canon of work is no exception. Her most acclaimed productions to date – Grey’s Anatomy and Private Practice – rely greatly on the indistinct subtext, which reassures us that anyone can survive (thrive, even) within the white male patriarchal world. That is, as long as they play the role demanded of them. Sadly, Scandal falls into the same trap. Though the characters are diverse in many ways, they are the same to the extent that each of them plays their role to preserve the system at all costs. And it is not just any system they are fighting to preserve: it is the American Political System under the fictional portrayal of the leadership of the Republican Party. The show relishes in essentialized representations of Republican Politicians (see characters Sally Fields and Hollis Doyle). However, these somewhat essentialized, fictional portrayals highlight an extreme irony of the show. Constituents whose support the actual Republican Party has in recent years struggled to garner – people of color, particularly black women (Olivia Pope), and gay folks (Cyrus Beene) – are fighting tooth and nail to uphold it.

On the surface, the show seems progressive. It is rare to see such a diverse and unlikely group of characters come together to fight for a shared cause within a mainstream TV show. Furthermore, Rhimes appears to break the normative Hollywood modus operandi wherein the protagonist is typically both male and white. In fact, she is portrayed as “the great white hope” who is required to save the day alone. But the assumed central character of Scandal, Olivia Pope, is neither white nor male: the flesh of a black woman appears to be at the center of this drama.

Although a black woman is allegedly at the center of the storyline, the standard “ingredients that make Hollywood Hollywood – sex, violence, violation and action – “ (hooks 122) are an ever-present force in Scandal. Little changes about the normative Hollywood M.O. other than the fact that Olivia Pope, a black woman, is the one allowed to save the day alone; or in her case, with a team of “gladiators.” But ultimately, everything hangs on Pope’s shoulders alone and her ability to work her magic. [Is Kerry Washington joining the ranks of Hollywood’s magical Negroes?]

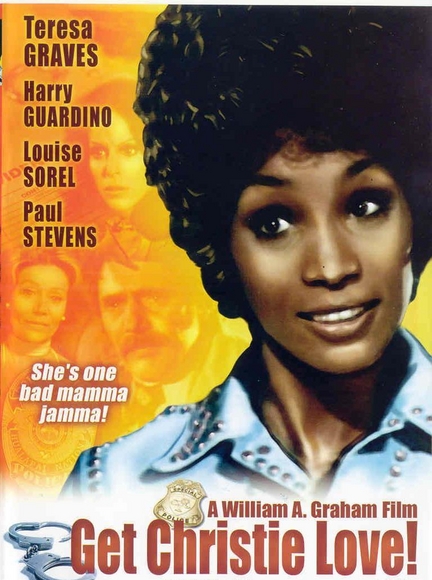

And we love it! We love seeing someone – especially a black woman –wield so much power at the flip of her hair, quiver of her lip, or with her cold blank stare. It is exciting to see a black woman playing the political game just as well as, if not better than, her white male counterparts. Moreover, there is something historic about the show. In a recent interview on Oprah’s Next Chapter, Kerry Washington discussed the fact that it has been nearly 40 years since a black woman has stared in a network drama in this capacity. The last time the American public saw similar casting was with the 1974 ABC drama “Get Christie Love!” starring Teresa Graves.

So the excitement over the show and the calls to celebrate a seemingly progressive image of a black woman on television are in some ways understandable. However, I contend something else is also happening on Scandal. The subtle clothing of Olivia Pope – black female flesh – in the garments of “the great white (male) hope” narrative should also give viewers pause.

So the excitement over the show and the calls to celebrate a seemingly progressive image of a black woman on television are in some ways understandable. However, I contend something else is also happening on Scandal. The subtle clothing of Olivia Pope – black female flesh – in the garments of “the great white (male) hope” narrative should also give viewers pause.

While some may call for us to celebrate the portrayal of a black woman in a way that seems new and creative, Scandal is actually peddling the same tired societal representations of black womanhood albeit under the guise of progressivism. When a white man is the protagonist the story is typically one of redemption for the white man and salvation for his non-white, non-male counterparts through and by his own redemption. But black flesh does not behave the same way when it is clothed in the garments of “the great white (male) hope” narrative. When black female flesh is at the center of the drama the result is quite different. Scandal shows us that even when black female flash is wrapped in “the great white hope” narrative, the restraints placed on black bodily performances in media are just too strong for that narrative to succeed.

First, let’s acknowledge that Olivia Pope is an amazingly flat character. While the incessant presence of yelling, sexual antics, conspiracies, cover-ups, etc. keep us glued to the television, they distract us from the fact that Pope possesses no real depth. The writers seem to believe that as long as all the parts are moving, and Pope is tugged to-and-fro by various political demands, we will not notice that nothing is actually happening with her character. We know little-to-nothing about her family/personal life, her educational/professional trajectory beyond the Grant Presidential Campaign and Administration, nor do we know the passions and motives fueling her actions. If this were standard for all characters on the show, this would be a moot point. However, we know quite a bit of background information about other characters on the show, particularly President Fitzgerald Grant, III (Tony Goldwyn), Olivia’s love interest.

When compared with the information we know about Fitz, the limited information we know about Olivia is magnified. We know Fitz’s wife and father, as well as a generous amount of information about his estranged relationships with each of them. We know about his (scandalous) military career. One might even suggest that the aforementioned relationships and career give us a better understanding of what possibly undergirds the passions and motives of the character.

And what of Olivia? Viewers are not privy to this type of information where her character is concerned. All we know is that this black woman committed herself to Republican Presidential Candidate, Fitzgerald Grant, and has been a fixture of his campaign and administration to varying degrees throughout the show. Thus, any depth Pope possesses is always connected to the American Political System and/or Fitz.

One might argue that this is a way of providing the character with a deep and meaningful storyline. It is, however, problematic when the type of information we are allowed to know about Pope is limited in this way and that limiting is not standard for other characters in the show. To date we know the least about the show’s three black recurring characters, Olivia Pope, Harrison Wright (Columbus Short), and Edison Davis (Norm Lewis).

The type of information we are allowed to know about Olivia is quite reminiscent of the ways black actors and actresses accent the story lines of white folks in television shows that do not claim to place them at the center of the drama. As a result of this sacrifice of significant character development, the character of Olivia Pope must rely on stale media representations of black women for the semblance of substance.

In most episodes Pope is little more than a political mammy mixed with a hint of Sapphire who faithfully bears the burden of the oh-so-fragile American Political System on her shoulders. The mammy characterization has always had the goal of redeeming the relationship between black women and the white people whom they serve, particularly in the slave economy. Post-slavery, the mammy image has been repackaged time and time again in order to imbed itself within an ever shifting culture. Pope is one of the latest manifestations of this characterization. Similar to how the mammy of slavery was normally portrayed as neat, clean, and happy to serve and maintain the inner-workings of the massah’s house; Olivia Pope is neat, clean, and well-dressed; she understands the inner-workings of massah’s house — The White House, and tirelessly works behind the scenes to ensure the house continues to function as expected. Furthermore, just as the mammy stereotype would have us believe, Pope is happy with her life of service to the good white folks running the country.

But she’s not always all smiles as we’d expect a typical mammy to be. Pope just as quickly puts her hands on her hips, hardens her facial features, and roles her neck ever-so-slightly letting us know that she won’t take anything lying down. Just like the Sapphire representation, Pope is up for a fight. But to only portray Pope as a political mammy with a hint of Sapphire would be too obvious to viewers and would make her character even more noticeably flat. So, the show utilizes the ingredients of sex and violation masked as a romance to make her character seem a bit more complex.

[Enter Jezebel stage left.]

When Pope is not gleefully maintaining the house or being overbearing, thus undesirable, she’s in the back shed with massah — the Oval Office — Fitz where we realize she’s actually quite desirable (see Season 1 Episode 1). President Fitzgerald Grant can’t keep his hands off of her. He continuously expresses his incalculable love for her, but can only seem to express this “love” by forcefully grabbing her and feeling her up whenever he gets the chance. In the very first episode he forces himself on her while she attempts to decline his advances. But because of our conditioning, we see Pope as a Jezebel: she really wants it, we think. So, we accept the violation and believe there’s nothing wrong with Fitz’s unwelcomed advances; apparently “no” really doesn’t mean “no” in this case. The problem is, sexual intrigue and force do not equal love. We have seen no actions that support Fitz’s claim to love Olivia; but we do have plenty that suggest she is the object of his sexual desire.

One must acknowledge that Rhimes has seemingly attempted to address these race and gender concerns in Season 2. The most clear ‘race’ conversation occurs in Season 2 Episode 8, when Olivia tells Fitz she’s starting to feel a little “Thomas Jefferson, Sally Hemings” about their relationship. Initially this seems like a point where the plot may turn and Pope may move on from the constant violation. Shortly thereafter, however, Fitz and Olivia meet in a garden where he accuses her of playing the race card because she knows he has a role to play as the leader of the free world. In a fit of rage he yells at her saying, “There’s no Sally or Thomas here! You’re nobody’s victim, Liv. I belong to you; we’re in this together!” And before Olivia can rebut he storms off. Fitz gets the final say in how their relationship is to be defined. But no matter what Fitz may claim or how romantic the storyline seems, the script is all too familiar, and we already know how the story ends. And the moral of the story, you ask? Black female flesh = object to be desired sexually; white female flesh = desirable/acceptable in every other way.

The second explicit conversation about ‘race’ occurs (briefly) in Season 2 Episode 12. Fitz, having recently cuddled with death, is now ready to divorce Mellie and move on with life – presumably with Olivia by his side. Cyrus quickly reminds Fitz, however, that Mellie, his wife, is pregnant. What’s more, he tells him “Now Liv is a lovely, smart woman – I can’t get enough of her – but she’s not exactly a hue that most of your Republican constituents would be happy about.”

Both of these ‘race’ conversations merely graze the surface of the complex race and gender concerns at play. Neither conversation seems to be an opportunity for transformation. Additionally, neither conversation seems to take seriously the web of representational dominance that Pope’s character is caught in. Both conversations function as tools to make the characters and viewers continue accepting the status quo. In an almost undetectable fashion, Rhimes highlights the problematic race/gender concerns at play, only to dismiss them and make them appear not to matter as much – at least not in her stories.

In spite of the crafty stereotype switching that occurs on a weekly basis, the character of Olivia Pope is the ultimate amalgamation of three of the dominant media narratives about black women. She seamlessly switches between each in ways that would lead us to believe she transcends them. In this way, Scandal very subtly tricks us into celebrating these images as opposed to being critical of them and demanding better.

So, all things considered, can we honestly suggest that Olivia Pope is the protagonist of this drama? The “great white (male) hope” narrative she is being forced into just doesn’t seem to fit her properly. Furthermore, the played out representations of black women that her character relies on for substance suggest that she is not truly the center of this drama, but merely ornamenting someone else’s story.

[Enter imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy stage right.]

Olivia Pope is actually a supporting actress in Scandal. The American Political System takes center stage and sets the tone of every episode. It is quite easy to miss if one isn’t looking for it. Because the show wants us to believe that Kerry Washington’s character is the protagonist – the great black female hope – the true protagonist cannot be embodied as a white man as it normally would. So instead the American Political System – with its foundation of imperialism and white patriarchal reasoning – is very subtly casted as the invisible protagonist.

While we would normally rely on the storyline of a white man named Jack [i.e., Jack Bauer (24), Jack Shephard (Lost)] to orchestrate the proceedings of a weeknight television drama, we must rely on the ebbs and flows of the American Political System to coordinate the plot in Scandal. Every episode centers on something that threatens to crack its foundation. In the same way that characters in 24 mindlessly respond to the intuition and violent interrogation techniques of Jack Bauer to save the country, the characters in Scandal also mindlessly respond to the ever-cracking foundation of the American Political System in order to do the same. Their ultimate goal? To make sure that the cracking foundation remains unnoticed, or at the very least accepted as okay/natural, by the general public.

Everyone plays their role in the process. Olivia Pope leads the other characters in this role playing by example; playing not only the one role that the system demands of her, but three of them. The only way Pope is empowered and seemingly in control is through service to the system that demands her powerlessness and capitulation. Ultimately, Scandal is not concerned with the life of Olivia Pope or portraying a black woman in a new way in spite of our celebrations of the show. It is concerned with the fragile foundation of the American Political System. It’s goal is to subtly train us in the ways of imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy and teach us that playing our roles is the only way to truly succeed and be happy within its confines. The show merely rearranges the elements of our world to make them more bearable and reassure us that political mammies like Pope are out there tirelessly fighting to maintain the system we so greatly desire to uphold.

_________________

*Term coined by bell hooks

bell hooks. Writing Beyond Race.

James Baldwin. “Mass Culture and the Creative Artist: Some Personal Notes.” The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings.

____________________________________________________________

Brandon is a blackmalefeminist, culture critic, and budding theological historian whose primary interests include identity, faith, and the intersectionality of oppression. Brandon is an M.Div student at Emory University and is currently studying abroad at the University of Göttingen (Germany). There he is ethnographically exploring Afro-Germanism, and searching for connections between theological responses to German Holocaust, South African Apartheid, and American Slavery.

204 Comments