Lourdes Portillo Retrospective at MoMA

A retrospective of the films/videos of Lourdes Portillo opens tomorrow, June 22nd, at the MoMA in New York. “Lourdes Portillo: La Cineasta Inquisitiva” celebrates the notable achievements of the San Francisco-based filmmaker. In the span of thirty years, Portillo has made over twenty films and videos whose topics range from human rights and feminicide to culture, family, and the nation. Her films/videos bear witness to injustice and suffering and convey the concerns of Latinas and Latinos across the Américas without sacrificing their dignity and vitality. Portillo’s marvelously evocative films place women at the center of her stories.

Portillo is a versatile filmmaker with a poet’s eye for detail. Her unorthodox approach to filmmaking pushes against widely held documentary norms, blending realist with poetic techniques, stretching the parameters of nonfiction through the use of humor, satire, and allegory, as she ventures into the larger social and political dynamics of Latina/o communities. Among my favorites is Portillo’s first subjective documentary, The Devil Never Sleeps (1984). A “melodocumystery”—a term Portillo coined to describe its hybrid style—The Devil Never Sleeps probes the unresolved death of her favorite uncle, Tio Oscar, who died under mysterious circumstances in Mexico.

In the course of her investigation, Portillo pierces through the veneer of family secrets, conflicting testimonies, and surprising contradictions in the personal and political life of her beloved uncle. The Devil Never Sleeps captures the disconcerting schism of her vision: Portillo’s adoration of Tio Oscar and her at times vexed position in the family. For audiences familiar with Mexican political culture, the allegorical element of the documentary is palpable: the intrigues, deception, and hypocrisy of this private family (Portillo’s) personifies the corrupt politics of the public, national family of the PRI, the political party that until the election of Vicente Fox in 2000 had ruled Mexico for over seventy years.

With The Devil and other films, Portillo has waged a gentle revolution in documentary aesthetics. In the wake of the Quincentenary, Portillo collaborated with the comedy trio Culture Clash to produce the experimental satirical video, Columbus on Trial (1992), as part of the hemispheric counter-commemorations of Christopher Columbus’ fated voyage. In La Ofrenda: Days of the Dead (co-directed with Susana Muñoz, 1988), the filmmakers juxtapose lyrical with didactic narrations of the Day of the Dead celebration among indigenous and Mexican communities in Oaxaca Mexico and its reworking by U.S. Latina artists and gay communities dealing with AIDS. Portillo’s tribute to the Tejana singer, Selena’s legacy, Corpus: A Home-movie for Selena (1999), is woven through stories of fandom, patriarchy, gender and queer performances. Her most recent film, Al más allá, pushes even further against standard documentary norms. Blending documentary with story-bound techniques, Al más allá features Mexican actress Ofelia Medina playing the part of Portillo, along with a fictitious crew, as the documentarian Portillo investigates the impact of the global drug trafficking industry on the lives of three fishermen from a small fishing community on Mexico’s “Mayan Riviera.”

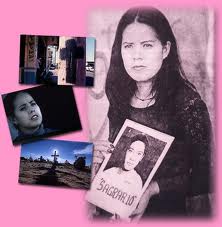

Among her finest documentaries to date, Señorita Extraviada (2001) investigates what was once considered Mexico’s number one human rights concern: feminicide in the violence-torn border city of Ciudad Juárez. At the time of the film’s release in 2001, close to 300 women and girls had been murdered and hundreds more disappeared; many were held in captivity and subjected to extreme forms of sexual violence, rape, and torture. The film documents the campaign for social justice headed primarily by mothers of the disappeared and murdered victims and supported by local women’s rights activists.

In portraying feminicide on the borderlands, Portillo aimed to change the hearts and minds of viewers. “The whole intention of the film was to create a kind of consciousness,” she says, “to incite people to act, and it did that.” Portillo became a crusader for women’s rights and the campaign to end gendered violence, screening the film before international audiences and raising awareness about the persistence of impunity throughout the region. Winning over twenty international awards, including Amnesty International’s first “Award for an Artist” and the Nestor Almendros Award from Human Rights Watch, Señorita Extraviada has screened before members of state and intergovernmental bodies like the European Parliament, the U.S. Congress, and the International Criminal Court, and forums like the 9th World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates in Paris. Apart from its screening at film festivals and “official” human rights venues, the documentary has shown before organizing and activist audiences in Latin America, the U.S., and Europe.

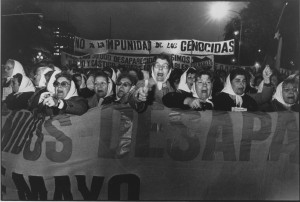

This is not the first time that Portillo has documented a human rights campaign led by women. Her earlier award-winning documentary Las Madres: The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (also co-directed with Muñoz, 1986) spotlights the plight of the mothers of the disappeared in Argentina. Set during the “Dirty War” waged by a military regime that ruled Argentina from 1976-83 and disappeared more than 11,000 civilians, mostly students, labor activists, and indigenous rights activists, the story is told from the perspective of the mothers who defied the ruling junta by staging weekly “illegal” demonstrations in the most guarded plaza of Argentina, the Plaza de Mayo.

Throughout her thirty years as a filmmaker, Portillo has consistently embraced an aesthetics of social justice rooted in political arts movements of the Américas, whose common denominator is a “poetics of transformation,” as Argentinean Fernando Birri explains, “a creative energy which through cinema aims to modify the reality upon which it is projected.” The poetics and politics of Portillo’s films share this passion for changing social worlds: “The art of film can be used in the service of the unprotected,” Portillo once explained, “and documentary can take a stance, and inform, activate, promote understanding and compassion…create a kind of consciousness to incite people to act.”

The retrospective of Portillo’s work, “Lourdes Portillo: La Cineasta Inquisitiva,” runs from June 22-30th at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The event is part of the commemoration of Women Make Movies’ 40th anniversary.

For exhibit details, click here.

12 Comments