Selling Sex (and Justice) in Orleans Parish

By Joseph J. Fischel

~sex for sale

Until last week, selling anal and oral sex in Louisiana was a registerable sex offense, on par with incest and sexual battery. You might reasonably ask why this was so, or whether the declassification of such a crime as a sex offense is particularly newsworthy. In fact, the development is monumental, the culmination of many years of tireless activism. In the near future, the lives of hundreds of women, some trans women, and a few men, most of whom are poor and African-American, will likely be vastly improved.

In Louisiana, sex offender registration entails, among other things, the label “Sex Offender” prominently featured in orange block print on one’s driver’s license, and publication of one’s personal information (picture, home address, etc.) on the Louisiana Sex Offender and Child Predator Website. Typically, sex offenders are required to announce their presence via postcards to neighbors and advertisements in the local newspaper, both of which the offenders pay for themselves.

On March 30, 2012, Judge Martin Feldman of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana ruled that the state could no longer compel those convicted of Crime Against Nature By Solicitation (CANS) to register as sex offenders.

To make sense of the ruling and grasp its gravity, some historical background is required. Louisiana criminalizes sex for money under two statutes: “prostitution” covers anal, oral, and vaginal sex for a fee; CANS, by previous judicial interpretation, covers anal and oral sex for a fee. However, until last summer, CANS convictions required sex offender registration. Prostitution did not.

CANS prosecutions have been disproportionately brought against poor women, women of color, and trans women. Police and prosecutors have discretion in determining whom to charge with prostitution and whom to charge with CANS. As a result, unlike any other state in the union, hundreds of Louisiana women are registered as sex offenders for nominally consensual activity. Poor, black women make up the vast majority of these convictions.

After extraordinary effort from Women With a Vision (WWAV), a New Orleans-based advocacy group serving underprivileged women, the Louisiana legislature equalized the penalties for each crime in August 2011. Now neither requires sex offender registration. WWAV, under the spectacular leadership of its executive director, Deon Haywood, brought public notice to the discriminatory consequences of CANS, and caught the attention of civil rights attorneys who later brought suit.

But until last week, those who had been convicted of CANS prior to August 2011 were still required to remain on the registry. Judge Feldman declared this requirement unconstitutional. If all goes right bureaucratically, the nine anonymous plaintiffs in the lawsuit, as well as hundreds of others convicted of CANS, will soon no longer be classified as sex offenders, with all the horrid publicity, restraints, and obligations the status entails. Rightfully, WWAV and the civil rights attorneys are ecstatic.

~whither political sympathy?

“if you rape a child, it needs to be branded across your damn forehead”

I spent the first six weeks of 2012 in New Orleans, interviewing women charged with CANS, men charged with other sex offenses, and activists involved in the declassification effort. My research is part of a larger academic project, but here I want to draw attention to just a few concerns I have with a dominant trope of the repeal project. The quotation above is from a local activist turned city hall staffer. As vehemently as she believes women convicted of CANS should not be labeled sex offenders, she likewise had no political affinity for the “other” sex offenders, those convicted of rape, sexual assault, or some form of sexual activity with a minor. This containment of political sympathy is entirely understandable; indeed, a dissociative logic—the moral and legal exoneration of one group through the vilification of another—pervades both the political arguments from WWAV activists and the legal arguments of the lawsuit. WWAV effectively argued that a main problem with CANS is that women convicted of sex work are regarded as predators. Likewise, the petitioner’s complaint emphasizes repeatedly that CANS is the only registerable sex offense that does not involve “force, coercion, use of a weapon, lack of consent, or a minor victim.” The women whom I interviewed were incensed that they were, as one informant said, “getting treated like somebody who went and raped a three year old.”

But what about these others, these rapists and child predators, or at least those convicted of “rape,” “attempted carnal knowledge of a juvenile,” and the like? I spoke with six such men while in NOLA, and I do not believe that any of them are threats to public safety. The obligations of registration have only further marginalized them from the community—they cannot sustain employment, afford home payments, or visit their children and grandchildren. Many men with whom I spoke were convicted of a single offense in the early or mid 1990s. A few did not know that their conduct—bathing a young girl, for example—qualified as a sex offense. Protested one offender, “It’s just hard man, when you’ve been branded.”

You might doubt the truthfulness of my interviewees’ accounts. Or perhaps I just talked to the six nicest guys of the lot. However, my interviews confirm a large body of existing research: sex offender registries do not work; they do not make communities safer; sex offenders recidivism rates are significantly lower than commonly perceived; registries neither change rape culture nor address the epicenter of sexual abuse—husbands, boyfriends, fathers, stepfathers, uncles, familiar faces. In Louisiana, Black and Brown men, usually socioeconomically disadvantaged, disproportionately fill out the roster of the Sex Offender and Child Predator Registry.

You might doubt the truthfulness of my interviewees’ accounts. Or perhaps I just talked to the six nicest guys of the lot. However, my interviews confirm a large body of existing research: sex offender registries do not work; they do not make communities safer; sex offenders recidivism rates are significantly lower than commonly perceived; registries neither change rape culture nor address the epicenter of sexual abuse—husbands, boyfriends, fathers, stepfathers, uncles, familiar faces. In Louisiana, Black and Brown men, usually socioeconomically disadvantaged, disproportionately fill out the roster of the Sex Offender and Child Predator Registry.

There is something troubling, then, about the dissociative logic of the CANS campaign, whereby one population deserves sympathy and solidarity while the other deserves only refusal and scorn.

~sex crimes on parade

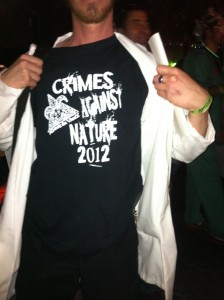

My research in New Orleans was winding down as Mardi Gras festivities were picking up. Although missing Fat Tuesday and other episodes of collective debauchery, I did witness the Krewe Du Vieux parade, what locals consider to be Mardi Gras’s kickoff affair. Krewe Du Vieux brings together bands of people (“subkrewes”), performers, artists, and activists who march in and around the French Quarter, often with intricate floats, paraphernalia, and thousands of giveaways for eager crowds. Each year the parade is themed to satirize an ongoing political controversy. In the past, parade participants have brilliantly caricatured FEMA’s breathtaking inefficacy, the gulf oil spill, and George W. Bush’s obliviousness. This year, Krewe du Vieux took on “Crimes Against Nature,” and the Queen of the parade was the indefatigable Deon Haywood.

Three things struck me about the parade.

First, its theme was “Crimes Against Nature,” that is, crimes, plural (the statute stipulates “crime,” singular). The title itself works a political invective against the statute: who’s not guilty? To the extent that we are having good sex, it’s probably sex that’s been criminal somewhere at some point. One float featured a wheel of fortune of sexual activities (“anal breach,” “hot wax,” “flog”), selectable by spinning the doll of a well-endowed, naked, bound woman. Why, the float (and the parade theme) seems to ask, are some bodies and sex acts scrutinized or moralized against more than others?

First, its theme was “Crimes Against Nature,” that is, crimes, plural (the statute stipulates “crime,” singular). The title itself works a political invective against the statute: who’s not guilty? To the extent that we are having good sex, it’s probably sex that’s been criminal somewhere at some point. One float featured a wheel of fortune of sexual activities (“anal breach,” “hot wax,” “flog”), selectable by spinning the doll of a well-endowed, naked, bound woman. Why, the float (and the parade theme) seems to ask, are some bodies and sex acts scrutinized or moralized against more than others?

Second, despite an explicit sexual theme lending itself to graphic representations, the floats were mostly muted, and often not about sex. In fact, most participants, organizers included, did not seem to know the intricacies of CANS or its political dramas. But why should they? New Orleans is itself a pride parade for no judgment. Instead, the Krewe du Vieux floats inventively performed solidarity with the Occupy Movement and the Arab Spring. When called upon to centralize criminal sexuality, these marchers invited its audience instead to deemphasize sex, drawing attention to growing social inequalities and political movements that affect us all (or 99% of us).

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Louisiana forbids its sex offenders from wearing masks on public holidays. Regardless of when the offense occurred, what it entailed, or whom it affected, offenders cannot cover their faces over Halloween and Mardi Gras. The people with whom I spoke could not participate fully in Krewe du Vieux, and many gloomily reported this prohibition to me. Now, you might not think this is the pinnacle of injustice: so what, it’s just a mask. Yet, insofar as New Orleanian citizenship privileges costuming, caricaturing, and public parading, the no-mask statute delivers damning humiliation. As metaphor, it is equally, unfortunately telling: in the ruthlessly indiscriminate, insistent drive to unmask the sex offender, to publicize his or her name and information online, through mail, and in newspapers; to expose him, like a bug under a magnifying glass, what have we accomplished? The Eastern District Court’s ruling is a remarkable achievement, but it is the beginning, not the end, of advancing a more just sexual politics in the Big Easy and beyond.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Louisiana forbids its sex offenders from wearing masks on public holidays. Regardless of when the offense occurred, what it entailed, or whom it affected, offenders cannot cover their faces over Halloween and Mardi Gras. The people with whom I spoke could not participate fully in Krewe du Vieux, and many gloomily reported this prohibition to me. Now, you might not think this is the pinnacle of injustice: so what, it’s just a mask. Yet, insofar as New Orleanian citizenship privileges costuming, caricaturing, and public parading, the no-mask statute delivers damning humiliation. As metaphor, it is equally, unfortunately telling: in the ruthlessly indiscriminate, insistent drive to unmask the sex offender, to publicize his or her name and information online, through mail, and in newspapers; to expose him, like a bug under a magnifying glass, what have we accomplished? The Eastern District Court’s ruling is a remarkable achievement, but it is the beginning, not the end, of advancing a more just sexual politics in the Big Easy and beyond.

______________________________

Joseph Fischel is the Carol G. Lederer Postdoctoral Fellow in the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women at Brown University. Next fall he will be an Assistant Professor of LGBT Studies in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program at Yale University. Fischel received his PhD in 2011 from the Political Science Department of the University of Chicago. His research interests are in public law, sex and gender studies, and contemporary political theory. He has published articles on the legal regulation of sexuality in the Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy and the Yale Journal of Law & Feminism. He is currently working on a book project titled, Sex and Harm in the Age of Consent, that interrogates the figures of the child and the sex offender, and the figuration of consent, in contemporary U.S. law and media culture.

Joseph Fischel is the Carol G. Lederer Postdoctoral Fellow in the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women at Brown University. Next fall he will be an Assistant Professor of LGBT Studies in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program at Yale University. Fischel received his PhD in 2011 from the Political Science Department of the University of Chicago. His research interests are in public law, sex and gender studies, and contemporary political theory. He has published articles on the legal regulation of sexuality in the Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy and the Yale Journal of Law & Feminism. He is currently working on a book project titled, Sex and Harm in the Age of Consent, that interrogates the figures of the child and the sex offender, and the figuration of consent, in contemporary U.S. law and media culture.

0 comments