Anti-Gay Marriage Group's Black Strategy Has Long History

By Kenyon Farrow

Last week LGBT rights advocates went into a state of shock when Human Rights Campaign (HRC) revealed documents by its arch-nemesis, the National Organization for Marriage (NOM). NOM has been using race as a way to drive a wedge between LGBT marriage equality advocates and African-Americans. The documents released by HRC show that NOM’s “strategic goal…is to drive a wedge between gays and blacks—two key Democratic constituencies. Find, equip, energize and connect African American spokespeople for marriage; develop a media campaign around their objections to gay marriage as a civil right; provoke the gay marriage base into responding by denouncing these spokesmen and women as bigots…”

Last week LGBT rights advocates went into a state of shock when Human Rights Campaign (HRC) revealed documents by its arch-nemesis, the National Organization for Marriage (NOM). NOM has been using race as a way to drive a wedge between LGBT marriage equality advocates and African-Americans. The documents released by HRC show that NOM’s “strategic goal…is to drive a wedge between gays and blacks—two key Democratic constituencies. Find, equip, energize and connect African American spokespeople for marriage; develop a media campaign around their objections to gay marriage as a civil right; provoke the gay marriage base into responding by denouncing these spokesmen and women as bigots…”

I don’t know why this comes as a shock, but the Christian Right and all the various organizations that align with the Right have been employing this strategy for more three decades.

The conservative movement employed homophobic rhetoric to turn LGBT concerns into wedge issues with African-Americans in the 1980s. The discovery of “gay cancer” in 1981 (which is now known as HIV) and the public hysteria that ensued as a result of the little information available on the disease, created fissures between faith and sexual politics in the Black community, as Dr. Cathy Cohen documents best in her book Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics. At the 1984 Democratic National Convention, Rev. Jesse Jackson, who had also unsuccessfully run for President that year, called for the formation of a “Rainbow Coalition” comprised of all groups who stood to lose ground from the “Reagan Revolution” including the poor, Arab, Native, Asian, Jewish and African Americans, youth, disabled veterans, small farmers, and lesbians and gays. Though Jackson was unsuccessful in his presidential campaign in 1984 and 1988, this rainbow coalition marked a significant effort to a progressive populist base to fight the neoconservative stronghold in American politics.

In my view, the Right’s attempt to appeal to the seeming homophobic sentiments of some African-American constituents as a way to prevent stronger coalitions with White LGBT groups was a direct response to the success of Jackson’s presidential runs, which employed really strong grassroots organizing tactics. In 1984, Jesse Jackson won primaries in five contests, and eleven when he ran in 1988, many of them in southern states like Mississippi and Louisiana—states we don’t even currently consider as having the most progressive Democratic bases. In response to Jackson’s success and the growing power of the LGBT movement, the Traditional Values Coalition and the Springs of Life Ministries released a video in 1993 targeted to Black Christian churches called Gay Rights, Special Rights: Inside the Homosexual Agenda. The goal of the video was to paint non-heterosexual people as only White and upper class, and as sexual pariahs, while portraying Black people as pure, chaste, and morally superior. The video juxtaposed images of White gay men from the leather/S&M community with the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, leaving conservative Black viewers with the fear that the Civil Rights Movement was being taken over by morally debased human beings.

In my view, the Right’s attempt to appeal to the seeming homophobic sentiments of some African-American constituents as a way to prevent stronger coalitions with White LGBT groups was a direct response to the success of Jackson’s presidential runs, which employed really strong grassroots organizing tactics. In 1984, Jesse Jackson won primaries in five contests, and eleven when he ran in 1988, many of them in southern states like Mississippi and Louisiana—states we don’t even currently consider as having the most progressive Democratic bases. In response to Jackson’s success and the growing power of the LGBT movement, the Traditional Values Coalition and the Springs of Life Ministries released a video in 1993 targeted to Black Christian churches called Gay Rights, Special Rights: Inside the Homosexual Agenda. The goal of the video was to paint non-heterosexual people as only White and upper class, and as sexual pariahs, while portraying Black people as pure, chaste, and morally superior. The video juxtaposed images of White gay men from the leather/S&M community with the voice of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, leaving conservative Black viewers with the fear that the Civil Rights Movement was being taken over by morally debased human beings.

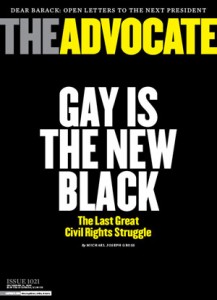

The Christian Right used that video as a grassroots movement building strategy to build support among socially conservative Black Christian ministers and their congregations to neutralize the support of LGBT rights by Black voters. It is true that polls have shown that Black voters are less supportive of same-sex marriage and think of “civil rights” as a very particular movement in the political history of African-Americans. Given this, conservative groups have worked tirelessly over the last 30 years at the grassroots level to make LGBT rights a no-go with Black voters; on the contrary, the LGBT movement has mostly used a rhetorical strategy of trying to make LGBT rights the next logical policy agenda after the Civil Rights Movement. At a panel discussion on LGBT issues at the NAACP National Convention last summer where I was also a panelist, NAACP CEO Ben Jealous made note of this very issue, saying, “I’m tired, quite frankly, of LGBT organizers who come to the Black community late with an expectation, and don’t treat us with the respect that they treat every other community, and showing up early, organizing heard, working late, building the relationships.”

The right-wing strategy on social issues like gay marriage or abortion is only part of the equation. What rarely gets analyzed are the ways in which voter suppression strategies employed by the right disproportionately impact African-American’s right to vote. Such strategies suppress the elements of the Black community that are most likely to be more friendly on LGBT issues.

The New York Times and other media outlets have reported that Republican lawmakers at the state level are increasingly passing laws requiring government issued IDs in order to vote. Many studies have shown the disparate impacts on poor people, African-Americans, young people, and senior citizens, and other marginalized groups. The Brennan Center for Law and Justice reported that 25% of eligible Black voters—well over 5 million people—do not possess government issued IDs. The same study reported that 11% of voting age Americans as a whole do not have government ID.

Some of the other voter suppression strategies include ending early voting or voting by mail that occurs in some states (and has been shown to be particularly popular among African-Americans), challenging the legal addresses of people facing foreclosure, and contesting names that somewhat match those of former prisoners convicted of felonies in states where former prisoners are barred for life from voting.

According to The Sentencing Project, nearly 13% of Black men and a total of 5.3 million people overall are ineligible to vote as a result of laws that ban people convicted of felonies from voting even after time has been served. These strategies inevitably impact young people, people of color, the disabled, transgender people (who often may not have identification that matches their gender transition), poor and working class people (who are often not allowed time off to vote).

So while LGBT activists often focus on the religious aspects of the Right’s strategy to undermine Black support on LGBT issues at the ballot box, they’ve spent far less time considering the impact of Black voter suppression policies that are just as necessary to the Right’s strategy. I don’t think voting or electoral politics is the answer to all that ails the world. Nor do I think that LGBT issues are the only reason the Right is interested in undermining Black people’s right to vote. But with so many people who currently cannot or are effectively dissuaded from participating, is it any wonder why the general electorate, including African-Americans, is so socially conservative?

So while LGBT activists often focus on the religious aspects of the Right’s strategy to undermine Black support on LGBT issues at the ballot box, they’ve spent far less time considering the impact of Black voter suppression policies that are just as necessary to the Right’s strategy. I don’t think voting or electoral politics is the answer to all that ails the world. Nor do I think that LGBT issues are the only reason the Right is interested in undermining Black people’s right to vote. But with so many people who currently cannot or are effectively dissuaded from participating, is it any wonder why the general electorate, including African-Americans, is so socially conservative?

But change is a foot. A 2010 survey by the Arcus Foundation showed that while Black Americans disliked LGBT constituents’ comparisons to the Civil Rights movement and opposed same-sex marriage, they overwhelmingly support other forms of relationship recognition for LGBT families, as well as ending other forms of discrimination against LGBT people in jobs, employment, and other aspects of public life. Additionally, a survey by the Black Youth Project at the University of Chicago showed Black youth who were less religious, and who listened to more hip-hop, were more open to LGBT issues—and yet it is these youth who are most likely to have their voting rights compromised.

Rather than panicking because you found proof that NOM has a strategy to undermine Black voter support for marriage equality, LGBT activists interested in electoral politics should be just as mobilized around who gets to vote at all.

_______________________________

Kenyon Farrow is a writer living in NYC. The research for this article informs an upcoming report to be published by Political Research Associates.

Kenyon Farrow is a writer living in NYC. The research for this article informs an upcoming report to be published by Political Research Associates.

4 Comments