Rejecting the Rhetoric of the “Second Shift” and Insisting on Equity

By Sara Hosey

At a recent meeting of a feminist group of which I am a member, a colleague referred to me as an example of a mother who has a “second shift” to look forward to when she leaves her academic job.

Though others nodded with understanding, I felt that these women were getting it all wrong.

“No,” I said. “That’s not right. I don’t work a second shift.” And then I self-righteously blurted out, “I’m in an equitable relationship!”

No one responded.

What I meant was that although I have the same responsibilities that many adults have (picking up a child, making dinner, washing dishes), I don’t have to do it all alone; my partner and I split these tasks as close to fifty-fifty as we can. I was astounded, actually, that other feminists would assume otherwise. Didn’t these women, many of whom came to feminism in the 1970s, share chores with their husbands and partners as well?

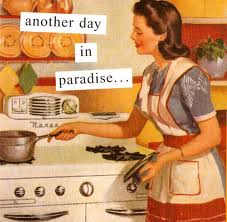

In addition to being surprised, I was left wondering why many of us continue to press for the definition of house cleaning and child care as a “second shift” of labor that (heterosexual) women must and do continue to perform. I understand how this rhetoric might have served us previously, in that claims such as “every mother is a working mother” drew attention to the time and energy many women put into tasks that were often invisible to or demeaned by men or others in the 9-5 work world. Yet at this moment, in this wave, the construal of home care and childrearing as work is no longer useful. In fact, it is offensive to those who aren’t engaged in sexist and/or heterosexual partnerships; it infantilizes women and many of the men we love; and it’s a capitulation to capitalism, ultimately undermining feminist attempts to valorize interpersonal relationships, caregiving, and cooperation.

Let’s be clear: inequitable relationships in the home are injurious and, unfortunately, they are entrenched. We in the United States should be ashamed that our official census describes a father’s parenting as a “child care arrangement,” that we countenance the lack of accessible, affordable, excellent day care, and that workplaces disincentivize caregiving of all kinds. But arguing that women work a “second shift” doesn’t necessarily challenge these realities; if it did, recent Bureau of Labor statistics wouldn’t confirm that women in America continue to do the bulk of childcare and housework. Further, in using this language we succumb to a kind of thinking that suggests that every pursuit, the most noble and the most mundane, is best understood in an economic model. Instead, I’d like to propose another way of looking at parenting, family life, and housekeeping: the basic activities of many adults’ lives. I, for one, don’t spend time with my child, talk to my partner, or do laundry because I expect or believe I deserve compensation.

I assert that defining parenting as “work” misconstrues what parenting can and should be. It demeans an otherwise complex relationship that is, at its best, definitively loving and mutually-rewarding, suggesting that it is in essence an economic exchange and that individuals are investments or commodities. Ideally, parents (and guardians and other family members) perceive spending time caring for their child as pleasurable enough to not require remuneration. This is not to suggest that there aren’t paid caregivers who don’t find their jobs fulfilling or that being with my child is always fun or even not-boring. We have plenty of articles, books, television shows, and blogs attesting to the tedium of parenthood. Similarly, we are well aware that spending time with family generally can be difficult; yet no one is arguing to categorize Thanksgiving as “work” or figuring out the cost of farming out the labor. Spending time with family is something that many of us do whether we like it or not because there are larger rewards to spending time with and taking care of other people.

On the other hand, defining housekeeping as work—if one is doing it for oneself, and not for pay—elevates a quotidian part of life. Most people find housekeeping unpleasant at best, and yet this is what adults who are not extremely wealthy (or extremely irresponsible) have to do with at least part of their time: take care of themselves and their immediate environments. Interestingly, not many people argue that we should call it “work” or a “second shift” when childless or single individuals clean their own homes and cook their own meals, often in addition to holding down paid jobs (as well as performing all sorts of other important social duties and/or meeting familial obligations).

Perhaps our energies would be better spent critiquing, rather than valorizing, housekeeping. Scholars have recently suggested that home size and standards of cleanliness have only risen with the advent of serious chemical cleaners, kitchen appliances, and other tools for home maintenance. This fact strikes me as echoing the cycle Naomi Wolf identified with regard to the beauty industry: that as women make political, economic, and social gains, the pressure to spend ever more money and time on one’s appearance increases. Similarly, as we make all sorts of gains in previously male-dominated fields and in our careers, the pressure to have and to maintain a pristine home increases. But just as we should actively resist the “beauty myth,” we should actively resist the myth of the perfectly-appointed home and the idealized figure of the woman who “does it all.”

I’m suggesting a lowering of one’s personal standards for political reasons, but I’m also suggesting that removing housekeeping from the category “work” might also allow us to remove it from the realm of the serious, generally; there are better, more empowered ways to spend one’s time and money than scrubbing and polishing. Cleaning your own home isn’t fun, but it isn’t work, either; what is work is the consciousness-raising and political lobbying, the thinking and writing and organizing that many of us have done and continue to do, often in addition to holding down paying jobs, picking up after ourselves, and spending time with our families.

In addition to resisting the impulse to understand our lives primarily in economic terms, we must begin insisting that the “second shift,” or sexism at home, is neither universal nor irresistible. Let’s be a little more honest with each other and a little less worried about calling out sexism when we see it, even when it is our friends and colleagues who are complicit in maintaining a sexist order. There’s something to be said for a positive kind of peer pressure. What if, rather than easy commiseration (i.e. “I know; men can’t load dishwashers!”), we mustered the same shock and disapproval usually reserved for homophobic or racist remarks when we are confronted with casual sexism? What if we pointed out that assumptions of domestic inequity naturalize sexism, that they are offensive to both men and women, and that they ignore other kinds of household arrangements?

Feminists should be identifying and exploding the myth that injustice at home is inevitable when we see it perpetuated, not only in our media, by our government, and in our communities, but also in our own lives and by our friends and colleagues.

________________________________________

Sara Hosey is an assistant professor of English and Women’s Studies at Nassau Community College in Long Island, New York. She is currently working on a book about representations of home and domesticity in American literature and culture.

Sara Hosey is an assistant professor of English and Women’s Studies at Nassau Community College in Long Island, New York. She is currently working on a book about representations of home and domesticity in American literature and culture.

4 Comments