Sticks and Stones

What is the appropriate response to Die, bitch?

Recently, I’ve had occasion to ponder this question and a broader cultural predicament in which all public speech has come to be perceived as “fighting words.” For the first time in my authorial life and counter to my fervent belief in freedom of expression, I removed from the public sphere something I had written. I feel good about the decision, too, in spite of my regard for the piece, which was sort of witty and certainly provocative. It was on a contemporary health movement that I defined as hyper-masculine and retro, with comparisons to the Republican primary. My words clearly touched a raw nerve; I was reminded of the blistering responses to Heather Laine Talley’s piece in TFW on “faux feminist men” and the barrage of misogynistic comments following a review in Salon of Lisa Jean Moore’s book on sperm.

It seems that when women speak (especially about men and their bodies), we must be silenced if not pilloried.

Some readers liked my article very much, and many offered thoughtful, constructive feedback. Yet several readers—not our usual TFW crowd, to be sure—wrote to inform me I was an ignorant, lazy, unethical, humorless bitch of a feminist. (One incensed man wrote, “Get. Over. Yourself.”) These responses were viscerally hostile and angry, as if the senders had eagerly waited for the perfect opportunity to unleash a torrent of invective. Seemingly lost on my respondents was that their missives did nothing to dispel the ideas about masculinity in my article. One of my favorites, although not among the most vile, was the respondent who chastised me for doing feminism a disservice (“is this really what feminism has come to?”). Of course, the rest of his commentary revealed that he did not give one iota of a damn about feminism or its goals.

It’s not that I’m particularly thin-skinned, at least not usually. After all, I have a healthy sense of humor and I’ve survived two decades of academic peer review, not all of it kind and generous. But with peer review, I’m accustomed to receiving—and providing—criticism of ideas, methods, epistemologies, and other scholarly aspects of somebody’s work. Rarely, if ever, does an individual’s personality or essence enter into the peer review process. Whether the scholar is an asshole, the loveliest person on the planet, or a terribly dull blade is irrelevant. The scholarship, including the quality of the writing, is at issue—not the person. Such was not the case with the many unsavory responses to my article; these were clearly meant not to dialogue but to wound, to put me in my place. And this is much easier to do on the Internet, where reaction requires nothing more than the push of a button.

Ten years ago, maybe even five, I would have responded to each and every ugly email with righteous gusto, thus escalating the skirmish simply to prove my point. Now, with the wisdom of time and age, I recognize that some battles are not worth fighting. Some minds will never be changed, and for many audiences, I will only and always be a humorless bitch of a feminist. And while pulling my article could certainly be seen as a kind of retreat, I prefer to think of it as a moment of feminist sanity in the war of words, in which verbal bombs can cause as much damage as actual sticks and stones. At the end of the day, given a choice between an in-box full of hate and peace of mind, I’ll take the latter every time. Self-care, as Audre Lorde noted, is critical to self-preservation and survival—and it keeps us invested in the long-term struggle. But temporarily removing myself from the blogosphere did not stop me from thinking about the tenor of those messages and the chilling effect of hate on free speech.

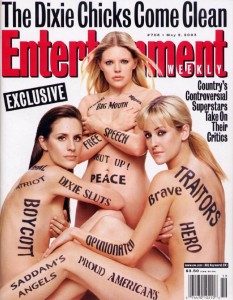

Consider the 2006 documentary Shut Up and Sing, about the Dixie Chicks. Once one of country music’s hottest bands, the Chicks took a nosedive in 2003 after lead singer Natalie Maines criticized President Bush from a London stage. Not only was Maines disparaged, she and her partners were utterly vilified. And the anger directed their way was clearly gendered. The trio was recast by their critics as “Dixie Sluts,” “Dixie Bimbos,” “Dixie Twits,” and “Saddam’s Angels,” among other sexist epithets. (The women offered their own clever commentary with a provocative Entertainment Weekly cover.) No country radio station in the southern U.S. would play their music, and Maines received death threats. As ironic as it is that country music, bastion of corporatized patriotism and muscular flag-waving, would attack freedom of expression, the onslaught was effective: the Dixie Chicks have not released a record since Taking the Long Way in 2006.

Such assaults are not always anti-woman. In his memoir Here Comes Trouble, intrepid documentarian Michael Moore writes of being under siege after he reproached President Bush and denounced the Iraq War at the 2003 Academy Awards. From hate mail to death threats, Moore’s life (and that of his family) changed for the worse. Ultimately, Moore was forced to hire not just one bodyguard, but nine ex-SEALS for 24/7 protection. At venue after venue, men tried to attack him with knives (Nashville), blunt objects (Portland), scalding coffee (Fort Lauderdale), pencils (New York), guns (Denver), and fists. Like any self-respecting human in the crosshairs, Moore stopped speaking in public and hunkered down at home with his wife and his misery. After more than two years, Moore finally reemerged in the public eye after seeing President Bush on television suggesting that Americans not give in to terrorists. Moore writes, “I felt like he was speaking directly to me…His terrorists were winning. Against me! What was I doing sitting inside the house? Fuck it! I opened up the blinds, folded up my pity party, and went back to work.”

Indeed.

Here’s a dirty little secret about social order: it’s not natural. The way things are is not because a divine being ordained men to be superior to women, or whites to inherit the earth and subjugate other races, or children to be seen and not heard, or corporations and fetuses to be considered persons while pregnant women are treated as pliable objects. The world is the way it is because we have made it that way, through struggle and resistance, through blood spilled and lives lost, through one step forward and two steps back. Freedom of speech is part of this epic struggle to continually remake the world, and not everyone is on the side of justice.

In a world awash in material risks, why are words so dangerous they must be met with violence and dehumanization? Why must those who speak out be silenced, policed, injured, or killed? When did democratic engagement and civil discourse become annihilation politics? And how will we ever find our way forward if we cannot and do not speak?

Pingback: What “Rape Sonograms” Are Really About | The Feminist Wire