Penn State Evil

By Charles E. Bowie

As a former athlete and football player I struggled in coming to terms with what happened at Penn State. The cult of masculine discourse surrounding football locker rooms and the structures of meaning associated with being “a man” blinded me to the possibility of Penn State. So blinded by these meanings that my initial response was, this cannot be true. I hope it is not true. That this experience had a deep impact on my experience has caused me to critically examine my previously taken-for-granted notions of masculine discourse in football locker rooms. More deeply, it has caused me to take another look at the linguistic conventions being deployed to shape social understanding of this case in particular.

The language repeated over several news outlets concerning the scandal at Penn State is, “tragedy.” A friend said to me that it was tragic, and initially I said what happened at Penn State was “unfortunate.” However, I felt like I was cheapening and downplaying what actually happened by saying it was unfortunate and by accepting the language tragedy as a descriptor of what I had been hearing and reading. In this article, I want to focus on tragedy and lay it against other theological language that seeps into the background in the naming of the situation as such. To name what happened at Penn State a tragedy leaves me with mixed feelings. On the one hand, I agree that that there should be sympathy for the boys. The aftermath of having to live with such a violation is definitely tragic. On the other hand, I insist that we must look into our philosophical and theological traditions and call forth the language of “evil.”

When I hear the word tragedy, several images appear at the forefront of my conscious life. I see Katrina and its aftermath. I think about the tsunami and its violent path of destruction. I reflect on the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and a massive loss of life. What makes these events tragic is suffering and the loss of life to impersonal forces. Human beings were living their everyday, ordinary lives and an inexplicable force latched onto their existence and led them to their demise. Understood in this way, tragedy has deep roots in Western Culture, stemming back to the Greek theater. One of the enduring aspects of the Greek tragedy was to induce sympathy in the audience for the primary characters. American philosopher Martha Nussbaum describes the early Greek tragedies as cathartic. Within the context of tragedy, victims “ask for compassion” as the state of affairs that befall them are “beyond their control.”[1]

As Nussbaum highlights and as the examples of Katrina, the tsunami, and the earthquake in Haiti above disclose, tragedy is our language for coming to terms with human suffering, victimization and death. The tragic induces sympathy, which we see result in relief aid for those who have undergone calamity. In some sense, I want to call what happened at Penn State a tragedy given the Greek understanding. For the boys who were raped, the experience is tragic in its consequences and their lives merit our sympathy and compassion. However, if we remain with the language of tragedy, I am afraid we take for granted that which exists at the center of Greek tragedies.

I contend that what happened at Penn State is better described using the language concerning the content and catalyst at work in Greek tragedy, namely, the power of evil. In case of Penn State however, the manifestation of evil is not impersonal as it is in many Greek tragedies. Rather, evil is moral, personal and systemic and was manifested in the actions of a man that parents and children gave their loyalty and trust.

American Pragmatist philosopher Josiah Royce describes evil in our experience as a “sense” of repugnance and intolerability towards some action or some state of affairs. His assumption is that human beings have a gut response to evil whenever and wherever it is present. Common gut reactions include “resistance,” “struggle,” shrinking against,” and “flight from” sources of trouble. Royce’s description of evil rings true to me particularly in this case because these are the types of responses being registered concerning Jerry Sandusky and Mike McCreary.[2]

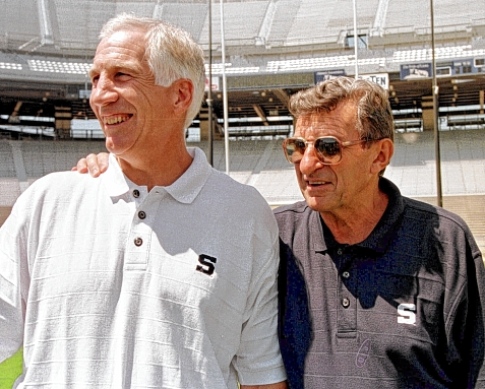

Sandusky’s actions were criminal and can rightly be categorized as rape. It is reported that Mike McQueary, wide receiver coach, and previous graduate assistant actually witnessed Sandusky assault a young boy in the Penn State locker room in 2002 and informed legendary coach Joe Paterno of the matter. In some sense, McQueary’s actions are equal to or worse than Sandusky’s. According to the grand jury report, he saw the assault and in that moment made a judgment that the body of this boy was not worth intervention. While he informed coach Paterno later, the repugnance and intolerable nature of it all is that he, again, per the grand jury report, did not intervene in the moment (notwithstanding McQueary’s recent email to a friend claiming otherwise). We might hypothesize he failed to act for future gain as he was promoted to the position of administrative assistant and later to wide receivers coach and recruiting coordinator. To see evil and accommodate it for the prospect of ones own future gain is rightly described by Royce as, “repugnant.”

The language of evil has been covered up and sidetracked in this case and must be brought to light. Language is crucial to shaping public understanding of these matters. My biggest fear is that labeling the case as tragedy will allow different standards of justice to be exercised for certain people and that our sense of repugnance and intolerability towards such is mitigated for sympathy. There is a sense of sympathy and compassion for the boys who were victimized. However, the forces that brought on their victimization were not impersonal. It was an abuse of power and influence by another human being that latched onto their experience. Thus, while there is a sense of sympathy and compassion, there is also outrage and disgust and a demand that responsibility be taken for ones actions. What happened at Penn State was not a tragedy. It was evil in one of its most brutal forms.

[1] Martha Nussbaum, Victims and Agents: What Greek Tragedy Can Teach Us About Sympathy and Responsibility. Boston Review: http://bostonreview.net/BR23.1/nussbaum.html

[2] Josiah Royce, “The Problem of Job,” in Studies of Good and Evil (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1906).

Charles Edward Bowie holds a Ph.D in Ethics and Society from Vanderbilt University. He teaches courses in Religious Studies (Sports and Religion; Spirituality and Medicine) at Vanderbilt University. His current work on Sports and Religion seeks to discover the possibility of a religious dimension to sports as well as the prospects of theological language for sports.

Charles Edward Bowie holds a Ph.D in Ethics and Society from Vanderbilt University. He teaches courses in Religious Studies (Sports and Religion; Spirituality and Medicine) at Vanderbilt University. His current work on Sports and Religion seeks to discover the possibility of a religious dimension to sports as well as the prospects of theological language for sports.

0 comments