On the Berkeley and Davis Protests

Back in February 2010, 11 Muslim students from UC Irvine and UC Riverside interrupted a speech given on the Irvine campus by Israeli ambassador Michael Oren to protest against that nation’s occupation of the Gaza strip. Although each protester only spoke for a few seconds, and although Oren’s speech was delayed by only a few minutes, the students were arrested and subjected to university sanctions. Afterwards, criminal charges were brought, at which point many students and faculty voiced their belief that this was a step too far. 100 UC Irvine faculty signed an open letter to the Orange County DA, asking that the charges be dropped. There was a wide consensus on campus that the DA’s increasingly Islamophobic and vindictive campaign against the students needed to end. Despite their efforts, ten of the eleven were convicted of criminal charges by the Orange County District Attorney in October 2011. At the time, faculty, students, and most people who read about the prosecution in the press worried what about the future of political expression on campus. Fears were hardly allayed by the administration’s statement that it still sought to “nurture robust debate, promote free speech, and welcome different points of view.”

Over the last week, we have seen those fears realized. I use the “Irvine 11” incident to open a discussion about the violent suppression of peaceful (and they were peaceful – linking arms is not a violent act, no matter what the Berkeley Chancellor might say) protests at Berkeley and Davis, because I realized today, to paraphrase Malcolm X, that the chickens have come home to roost. The actions we have seen this week appear to me as part of a longer trend in which the university proves itself willing to silence its students, and to renege on its supposed commitment to political engagement. Because while criminal charges against the Irvine 11 seemed unnecessary to many, for a significant portion of the community, the university’s own sanctions against the protesting students belied a desire to stifle free speech. While it could be argued, as administrators did, that Oren lost his right to free speech when the students drowned out his words, he was able to give his speech shortly after. He then cut short the Q & A to attend a Lakers game. The students, who weren’t backed by a government, exercised their rights to protest (peacefully) and were penalized. When the university temporarily banned the Muslim Student Union and imposed further individual punishments, many students worried about the potential consequences of voicing their political opinions. The administration emailed students shortly after the arrests, explaining that they encouraged free speech in “designated areas,” where it would not disturb anybody’s work. Apparently speech was only free where nobody could hear it.

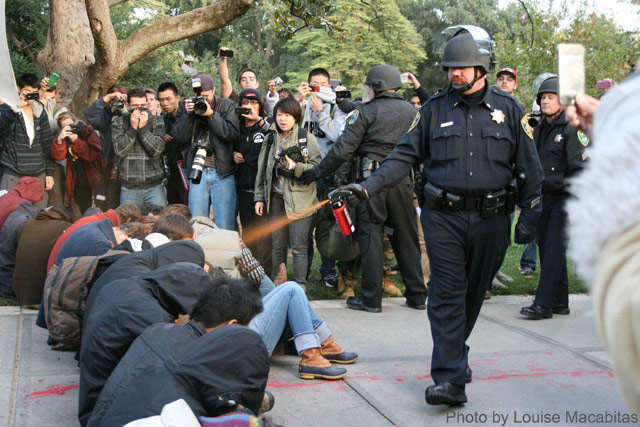

Now, when students on other UC campuses have confronted authority and articulated their grievances in a way that, at worst, caused a minor inconvenience, they have been met with riot police wielding batons, tear gas, and pepper spray. Nobody was rioting in Berkeley and nobody was rioting in Davis. The highest ranking officials at both institutions thought a reasonable response to a minor inconvenience was to call in heavily armed police. The police thought a reasonable response to the minor inconvenience was to pull protesters by the hair, hit them repeatedly with batons, and today, to hold their mouths open and pour pepper spray down their throats. The disparity between protesters’ peaceful action and the administration and police’s violent response is so large that it defies description. And the administration is equally responsible for the injuries protesters have unnecessarily suffered. The blood of UC students and faculty is on their hands too. Davis professor Nathan Brown has written a letter to the Davis Chancellor, Linda P. B. Katehi , demanding her resignation, because as he says, her decision making has compromised the safety of Davis community. What happened at Berkeley last week made it obvious that police cannot be trusted to restrain themselves, and Katehi should have known this.

On top of the grievous injuries done to people who did what they had every right to do in an organized, peaceful manner, the outcome of all this is a suppression of the very free speech upon which the University of California, the academy at large, the country, and the peaceful areas of the world rely. I have been a graduate student at UC Irvine for two and a half years, and I was once proud to be a part of one of the best public university systems in the world, a university with a tradition of political engagement. Now I am ashamed to be a part of an institution whose government thinks that speech should only be free in certain areas, that riot police have a place on campus, that linking arms denotes violence, and that use of weapons is a proportionate response to peaceful action.

The police need to be held accountable, just as they should have been in Oakland, New York, and countless other cities across the country in the last few months. Brutality seems to have become the norm, and the casual manner in which a policeman sprayed a line of protesters with a poisonous gas in Davis speaks volumes about how comfortable some policemen are with the injuries they inflict. That these people are allowed to act like this against innocent victims anywhere, on campus or off, without reproach, beggars belief. UC administrators who have allowed this to happen, like city mayors have, must also be stopped. Just as appointed administrative officials don’t think twice about unleashing an armed force on defenseless protesters everywhere, so many member s of police everywhere don’t think twice about using those arms. Both of these habits need to end here and now. This is a society-wide problem in need of immediate and drastic redress.

0 comments