It Matters what Team You Play For: Heteronormativity in Sports

Oscar Wilde once described the game of Rugby as “a good occasion for keeping thirty bullies far from the center of the city.” While Wilde may have been somewhat dismissive of a sport that requires considerable skill, courage, and physical fitness, he did point to the reputation, often deserved, that players and fans of the sport have. To those unfamiliar with rugby, I would say the nearest stateside equivalent is American football. While there are some distinct differences between the two games, they have fairly similar means of scoring, a similarly high level of physical contact, and even a similar shaped ball. Like American football, rugby is, in countries where it’s popular, often held up as the ideal of manly physical toughness. This commitment to and idealization of a sense of manhood that is always heterosexual perhaps explains why rugby players come across as bullies.

In the minds of coaches, players, and spectators, the conflation of sporting proficiency with sexual and gender identity is endemic. I have been told more than once that sports I watch and play, like rugby and football (soccer), are considered “girls’ sports” in the United States. And across the world, homophobic or gendered slurs are rife: in rugby and American football alike, the accusation that a player “throws like a girl” is equally common, and considered equally derogatory. When watching sports, how often have you heard a player that holds back in a tackle, feigns contact to win a foul, or misses an easy chance to score, labeled a “fag” or something similar?

A distinct line has been drawn in the popular imagination between the heterosexual manly sportsman, and the effeminate homosexual who shows no interest in, or has little aptitude for, competitive sports. It is a well policed border. The Daily Mail, a tabloid so reactionary and moronic that it barely deserves the title “newspaper,” ran a story last week about a rugby player, Chris Birch, who broke his neck, suffered a stroke and “woke up” gay. Not only does the author seek to pathologize homosexuality – same-sex desire is portrayed merely an inconvenient side-effect to a near fatal injury; a form of “brain damage” – he also equates homosexuality with a habit that is learned, and therefore can presumably be unlearned. If another stroke victim found he had a new ability to “paint and draw in incredible detail” when he regained consciousness, why wouldn’t someone be able to wake up gay? Because if the artist had developed his skill when the stroke “‘flicked a switch’” in his brain, the hope remains for any homophobic readers of the Daily Mail that somehow homosexuality might one day be turned off or cured.

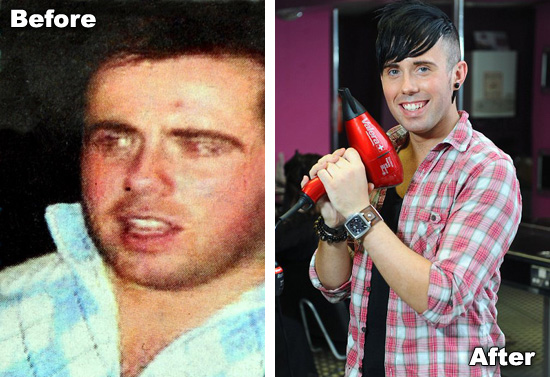

Just as problematic though, is the distinction drawn between Birch’s life pre-stroke (he weighed 19 stone [266 pounds], worked in a bank, played rugby, was engaged to a woman, and “never even had any gay friends”) and his life post-stroke as an 11 stone (154 pounds) hairdresser with a boyfriend, who “hates sports.” Whether or not there is any truth to Birch’s outlandish claims of “turning” gay (more than one critic has pointed out the extreme measures some people feel forced to adopt in order to come out), the article relies on and reiterates a punitive cultural investment in social separation. On one side we have a physically intimidating man interested in sports, with a respectable profession and heterosexual orientation; on the other we have a smaller man with lack of interest in sports, a stereotypically effeminate profession, and homosexual proclivities. The unwritten rule remains that anyone who doesn’t like sports, or has a certain kind of job, must be gay, or at least somehow less of a man. And if you are gay, you cannot like sports, but must instead be interested in things like hairdressing.

For those caught in the middle of such an arbitrary opposition, social acceptance can be hard to achieve. Paradoxically, rugby is one of few sports to have had an openly gay player in Gareth Thomas. Thomas’ decision to come out was undoubtedly brave and praiseworthy, but the fact the decision required bravery at all reminds us that considerable fear of social exclusion remains for gay athletes, as it does for gay people in all walks of life. It’s telling that Thomas revealed his true sexual identity only towards the end of his career and after having attempted to pass for straight until that point. The time it took for him to make the announcement speaks volumes about a rational fear of homophobia, as does his deliberate attempt to separate his sexual desires from his athletic performance. Thomas should be correct in his claim that “what I choose to do when I close the door at home has nothing to do with what I have achieved in rugby,” but the recent Daily Mail article proves that many people cannot distinguish between sporting ability/appreciation and sexual orientation. The fact that the expected homophobic reaction barely materialized after Thomas came out (at least in public – whether private conversations about Thomas were equally open-minded is open to question) was refreshing, but the expected trend of announcements from other gay athletes didn’t materialize either. Rugby remains an overwhelmingly heteronormative world, with Thomas an exception rather than vanguard of a new movement. While so many people define true manhood in narrow terms of heterosexuality and sporting ability, those people who do not fit the pattern will feel forced to remain silent. The Daily Mail certainly isn’t helping.

In the United States, an openly gay athlete, at least in the more popular sports, is even harder to find. The nearest that American Football has come is the addition of legal protection for openly gay players to the collective bargaining agreement. Whether the measure is sufficient to encourage any players to actually come out remains to be seen, but nobody will be holding their breath. In U.S. sports, the boundary of heteronormativity has a double guard. Beyond the first line of homophobia and social custom is the “morality clause” in major endorsement deals – contracts that most players crave, and only the most gifted attain. To receive the multimillion-dollar reward of representing a brand, players must live a life of which the average customer would supposedly approve. Homosexuality doesn’t sell, meaning that silence is golden: if a player wants to take full economic advantage of his profession, he must pass for straight. It might initially seem that a few brave sportsmen or a corporation willing to temporarily forego maximum profits is the only thing required to break the mold. But we know from the case of Gareth Thomas that one role model alone cannot reform a sport, let alone a society.

And if corporations are correct and sports fans really will not buy products advertised by a gay athlete, something is seriously wrong with social logic. Because this is a sport in which a convicted abuser of animals signed new endorsement deals after being released from prison; a sport that, at the college level, prompted fans to riot in defense of a coach who covered for his child abusing assistant. I could cite the several rape accusations made against players as further examples, but the reluctance to prosecute football players (a practice that reveals another social hierarchy the sporting world reifies), means that these almost always remain accusations only. Nonetheless, if failing to report pedophilia to the police or dogfighting is more morally reprehensible than same-sex desire, we need to seriously reevaluate society’s priorities. Morality clauses seem anything but moral.

This kind of logic exists outside of sports too: after all, more U.S. states allow someone to marry a cousin than marry someone of the same sex, and bullying is protected in Michigan as long as the bully’s bigotry is backed by religious belief. As long as this brand of reason – in which those who prey on the weakness of others are rewarded – persists; as long as culturally powerful institutions like state governments, major sports leagues, corporations, and the media follow suit; we will likely continue to define true personhood in terms of a particular sexual orientation or kind of talent. It has often been said that “the moral majority is neither.” It seems the statement was only half right.

0 comments