Who’s Afraid of Mildred Pierce?

One of the central premises of Betty Friedan’s germinal text, The Feminine Mystique(1963), is that the robust effort to restore American women to their rightful “estate”—home and family—was mounted on the back of an unrelenting assault of propaganda: in the immediate post-war era, educators, including presidents of women’s colleges, the clinical establishment, including psychologists and experts on parenting, advertising agents and magazine editors all effected common cause in the execution of what turned out to be a threefold interrelated mission that 1) altered the existential horizon of the American woman by relocating the origin of her self-image and identity in the home, which, in turn, 2) drove her out of the market place and competition for labor, which did its job by 3) ”marketizing” or commodifying “home” as a crucial site of corporate profit in the triumphant business culture of the United States. In the shifting face of American labor, it was unthinkable, then, that women would measure their achievements, their ambitions, their competence by any yardstick other than the distaff. While the picture that Friedan draws here is colored by her own experiences as a white, upper class, well-educated female, its general applicability to intersectional theory and the post-war fate of black women and women of color is useful by contrast; in other words, the revised mythology of the post-war feminine and the revisited “cult of true womanhood” that accompanied it would constitute the background against which the modern movement in civil and human rights would unfold. For instance, Rosa Parks’s act of “civil disobedience” would be all the more poignant because she was a working woman. That thousands of white suburban housewives—inhabitants of spaces carved out of the hide of the southern city because Brown v Board (1954) had initiated massive white flight, brought on by the Supremes Court charge to desegregate the nation’s public school districts—would never need to take the life risks that propelled Parks to national attention loudly proclaimed the bankruptcy of the new mythemes. We, therefore, bring to The Feminine Mystique whatever advantages may be yielded from the vantage of a “double consciousness.”

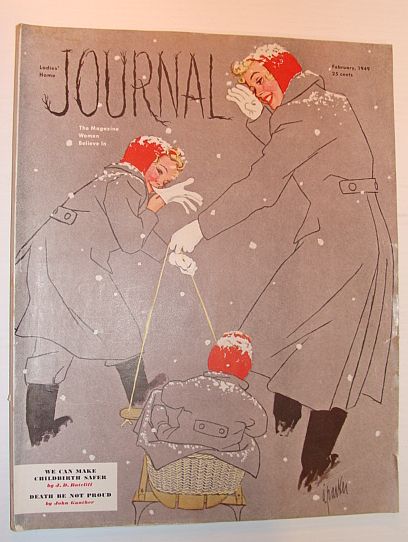

But from whatever angle of vision we take in Friedan’s arguments, we are confronted by the enormous work of popular culture then and now. In the second chapter of the text, Friedan ushers the reader along the path of research and discovery that would lead her to write The Feminine Mystique, and we are surprised to learn that the heroines of women’s magazine stories—in Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, Woman’s Home Companion—from the world of the late 1930s “were career women—happily, proudly, adventurously, attractively career women—who loved and were loved by men.” While the stories were conventional in their pursuit of heterosexual romance, the heroines themselves, as Friedan describes them, “were usually marching toward some goal or vision of their own, struggling with some problem of work or the world, when they found their man.” Friedan’s “New Woman,” “less fluffily feminine” than the subject of the “feminine mystique,” tended to independence and the determination “to find a new life of her own.” Almost never housewives, these magazine heroines looked to an open future, and in one notable instance, Sarah of “Sarah and the Seaplane” (Ladies’Home Journal, February 1949) learns to fly. These few remarkable sentences catch the eye:

But from whatever angle of vision we take in Friedan’s arguments, we are confronted by the enormous work of popular culture then and now. In the second chapter of the text, Friedan ushers the reader along the path of research and discovery that would lead her to write The Feminine Mystique, and we are surprised to learn that the heroines of women’s magazine stories—in Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, Woman’s Home Companion—from the world of the late 1930s “were career women—happily, proudly, adventurously, attractively career women—who loved and were loved by men.” While the stories were conventional in their pursuit of heterosexual romance, the heroines themselves, as Friedan describes them, “were usually marching toward some goal or vision of their own, struggling with some problem of work or the world, when they found their man.” Friedan’s “New Woman,” “less fluffily feminine” than the subject of the “feminine mystique,” tended to independence and the determination “to find a new life of her own.” Almost never housewives, these magazine heroines looked to an open future, and in one notable instance, Sarah of “Sarah and the Seaplane” (Ladies’Home Journal, February 1949) learns to fly. These few remarkable sentences catch the eye:

Then she drew a deep breath and suddenly a wonderful sense of competence made her sit erect and smiling. She was alone! She was answerable to herself alone, and she was sufficient.

An old-movies buff might recall a single scene from “Christopher Strong” (1933)—the Kate Hepburn character in silver lame, no less, piloting a small, single-engine plane, could well be Sarah, alone and sufficient! Friedan’s narration of the magazine editors’ change of mind (seduced by the doxa of capitalist greed) is sharp and dramatic:

And then suddenly the image blurs. The New Woman, soaring free, hesitates in midflight, shivers in all that blue sunlight and rushes back to the cozy walls of home.

Although Friedan does not address the role of movies in her choreography of America’s emergent new tastes, it is not out of the question to imagine cinematic change regarding the character of the heroine along lines of development that parallel the cosmos of women’s magazines.

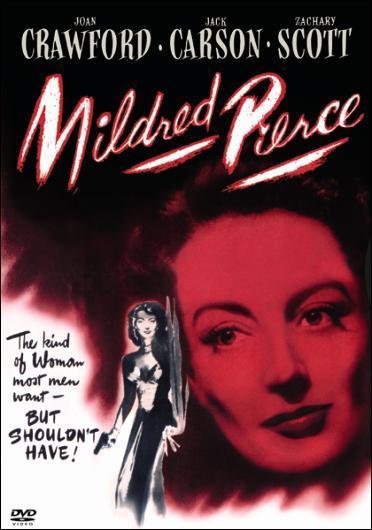

Recently watching episodes from the Home Box Office remake of “Mildred Pierce,” with Kate Winslet in the eponymous person of this talented, neurotic figure, I was inevitably drawn into making comparisons between Winslet’s “delivery” of the goods, as it were, and that of the “original” Mildred, performed by Joan Crawford in Michael Curtiz’s 1945 treatment of James Cain’s novel of the same title. Though it would be difficult and unnecessary to decide which one “wins” in my estimation, inasmuch as the two versions, in their radical divergence along every line of cinematic measure, do different work, I somehow prefer Joan Crawford’s big-eyed intensity, piercing gaze and formidable self-presentation to Kate Winslet’s studied movements, unpredictable volatility and brittle stressfulness, which traits of character all seem to serve her better in “The Reader,” or “Revolutionary Road,” for instance. Winslet’s Mildred looks as though she might topple over any moment now, while Joan Crawford’s, swinging her hips around in that fabulous mink coat, with matching hat, and wise cracking Jack Carson all the time, wouldn’t fall down even if she were ordered to, and who in the world would dare mandate Joan Crawford to do anything? (Betty Davis, as in “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?”?) But that’s just it about JC—whatever movie in which she appears becomes a “vehicle” for the disclosure of the forcefulness of a powerful persona, and here I refer to vintage Crawford of the mid-1940s, especially “Mildred Pierce” (for which performance Crawford won an Oscar) and “Humoresque” (1946).

Recently watching episodes from the Home Box Office remake of “Mildred Pierce,” with Kate Winslet in the eponymous person of this talented, neurotic figure, I was inevitably drawn into making comparisons between Winslet’s “delivery” of the goods, as it were, and that of the “original” Mildred, performed by Joan Crawford in Michael Curtiz’s 1945 treatment of James Cain’s novel of the same title. Though it would be difficult and unnecessary to decide which one “wins” in my estimation, inasmuch as the two versions, in their radical divergence along every line of cinematic measure, do different work, I somehow prefer Joan Crawford’s big-eyed intensity, piercing gaze and formidable self-presentation to Kate Winslet’s studied movements, unpredictable volatility and brittle stressfulness, which traits of character all seem to serve her better in “The Reader,” or “Revolutionary Road,” for instance. Winslet’s Mildred looks as though she might topple over any moment now, while Joan Crawford’s, swinging her hips around in that fabulous mink coat, with matching hat, and wise cracking Jack Carson all the time, wouldn’t fall down even if she were ordered to, and who in the world would dare mandate Joan Crawford to do anything? (Betty Davis, as in “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?”?) But that’s just it about JC—whatever movie in which she appears becomes a “vehicle” for the disclosure of the forcefulness of a powerful persona, and here I refer to vintage Crawford of the mid-1940s, especially “Mildred Pierce” (for which performance Crawford won an Oscar) and “Humoresque” (1946).

In both performances, Crawford exemplifies that ensemble of elements that we associate with the old Hollywood “star system.” For all its flaws and short comings, not the least of which was the imposition of severe constraint on the careers of black actors, the old system, in its projection of the “leading lady,” ironically conveyed a sense of female empowerment. Mildred Pierce’s tale is that of a housewife driven to seek fulfillment beyond the confines of the domestic sphere; the mother of two daughters, one of them pathologically spoiled and overindulged, and the wife of an earnest dutiful husband, Pierce belongs to a repertoire of women characters who will model early on the subject of feminism finding her way from scratch. It doesn’t particularly help, though, that Pierce’s ambitions appear to be overdetermined and raw, but we accept the portrayal as the price of the ticket that her personality must pay along the trajectory from rags to riches. Coming into her own as the chief executive officer of a successful, upscale dining establishment, Mildred pulls out all the stops to reach her dreams, even social climbing in the process. The trick of the tale, however, is that the version of the “American Dream” enacted here will curdle precisely because Pierce’s idea of success is gauged in material terms alone. Nothing signals the hollowness of this notion and of Pierce’s well-laid plans more poignantly than the tale’s denouement, when, sitting at a police interrogation, dressed to kill, Pierce lies about the murder of her second husband, Monty/Zachary Scott, as the lie fritters away in moral blunder. This character, we decide, would and could kill for daughter, Veda/Ann Blyth, but she didn’t do this murder, for which crime she has attempted to assume blame, and in the unambiguous logic of this morality tale, truth will out.

In both performances, Crawford exemplifies that ensemble of elements that we associate with the old Hollywood “star system.” For all its flaws and short comings, not the least of which was the imposition of severe constraint on the careers of black actors, the old system, in its projection of the “leading lady,” ironically conveyed a sense of female empowerment. Mildred Pierce’s tale is that of a housewife driven to seek fulfillment beyond the confines of the domestic sphere; the mother of two daughters, one of them pathologically spoiled and overindulged, and the wife of an earnest dutiful husband, Pierce belongs to a repertoire of women characters who will model early on the subject of feminism finding her way from scratch. It doesn’t particularly help, though, that Pierce’s ambitions appear to be overdetermined and raw, but we accept the portrayal as the price of the ticket that her personality must pay along the trajectory from rags to riches. Coming into her own as the chief executive officer of a successful, upscale dining establishment, Mildred pulls out all the stops to reach her dreams, even social climbing in the process. The trick of the tale, however, is that the version of the “American Dream” enacted here will curdle precisely because Pierce’s idea of success is gauged in material terms alone. Nothing signals the hollowness of this notion and of Pierce’s well-laid plans more poignantly than the tale’s denouement, when, sitting at a police interrogation, dressed to kill, Pierce lies about the murder of her second husband, Monty/Zachary Scott, as the lie fritters away in moral blunder. This character, we decide, would and could kill for daughter, Veda/Ann Blyth, but she didn’t do this murder, for which crime she has attempted to assume blame, and in the unambiguous logic of this morality tale, truth will out.

Today’s interest in “Mildred Pierce” not only centers in our lively and ongoing curiosity about Joan Crawford (later on, an actual CEO of Pepsi Cola) as a powerful female figure strutting her stuff before the loving gaze of the camera—Crawford veritably commands the “look”—but also the film’s relentless attention to a mimetic view of women in relationship, all the more agonizing in this case because the characters are playing out the significant drama of mother and daughter. There is no “b” word bull here—husband-stealing daughter Veda is an outright—let’s hear it—bitch. And old Hollywood, so driven by testosterone and alpha maleness, the story goes, did not fear its spectacle. This film noir instance might well be one of our few available studies of Melanie Klein’s maternal “bad breast.”

Today’s interest in “Mildred Pierce” not only centers in our lively and ongoing curiosity about Joan Crawford (later on, an actual CEO of Pepsi Cola) as a powerful female figure strutting her stuff before the loving gaze of the camera—Crawford veritably commands the “look”—but also the film’s relentless attention to a mimetic view of women in relationship, all the more agonizing in this case because the characters are playing out the significant drama of mother and daughter. There is no “b” word bull here—husband-stealing daughter Veda is an outright—let’s hear it—bitch. And old Hollywood, so driven by testosterone and alpha maleness, the story goes, did not fear its spectacle. This film noir instance might well be one of our few available studies of Melanie Klein’s maternal “bad breast.”

Friedan, Betty (2001), The Feminine Mystique with an intro. by Anna Quindlen. New York: W.W. Norton.

16 Comments