Astonishing Embodiments: Poetry and Feminism from Molly Sutton Kiefer

By Molly Sutton Kiefer

I remember that heady time of my undergraduate years when I was so anxious to change the world–that requisite minor in Women’s Studies, that producing of The Vagina Monologues, that tradition of Take Back the Night. I felt fierce. And I graduated and I panicked (a job? a job? where to find one?) and became a bit lackluster, a bit dulled—my fierceness was trying to stay head-above-water when teaching in a conservative school district. Fear of firing and the shock that getting pregnant before wedlock would actually be an issue, I’m glad to say that time of my life ended and I returned to the university, where I met a group of women that eventually became the Caldera Poetry Collective. This company, this freedom allowed me to feel empowered again and when I began to grow a daughter inside of me, I was pleased—I would help her become fierce too! But parenthood is a confusing time, and again, I had to readjust my thinking on feminism: I confessed to a fellow mama and close friend (who birthed her own towheaded daughter just two weeks or so after my own) that I felt like a “bad feminist”—I wanted to stay home with my daughter. Shouldn’t I be out there, fighting the good fight, breaking glass ceilings and the like? She reminded me: feminism is about choice. It’s amazing how freeing that was. So much is about permission—giving myself permission—and by staying at home, I’ve filled that mythic spare time (no bon-bons here) with so many good things: I run Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts | an Interview Project; I am launching a poetry journal called Tinderbox on June 21st and it’s going to really be amazing; I read manuscripts for a small press and write reviews for PANK and The Rumpus; I am a mentor for a prison writing workshop; I’ve got one manuscript being considered at presses and another in the solid generating stages.

I remember that heady time of my undergraduate years when I was so anxious to change the world–that requisite minor in Women’s Studies, that producing of The Vagina Monologues, that tradition of Take Back the Night. I felt fierce. And I graduated and I panicked (a job? a job? where to find one?) and became a bit lackluster, a bit dulled—my fierceness was trying to stay head-above-water when teaching in a conservative school district. Fear of firing and the shock that getting pregnant before wedlock would actually be an issue, I’m glad to say that time of my life ended and I returned to the university, where I met a group of women that eventually became the Caldera Poetry Collective. This company, this freedom allowed me to feel empowered again and when I began to grow a daughter inside of me, I was pleased—I would help her become fierce too! But parenthood is a confusing time, and again, I had to readjust my thinking on feminism: I confessed to a fellow mama and close friend (who birthed her own towheaded daughter just two weeks or so after my own) that I felt like a “bad feminist”—I wanted to stay home with my daughter. Shouldn’t I be out there, fighting the good fight, breaking glass ceilings and the like? She reminded me: feminism is about choice. It’s amazing how freeing that was. So much is about permission—giving myself permission—and by staying at home, I’ve filled that mythic spare time (no bon-bons here) with so many good things: I run Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts | an Interview Project; I am launching a poetry journal called Tinderbox on June 21st and it’s going to really be amazing; I read manuscripts for a small press and write reviews for PANK and The Rumpus; I am a mentor for a prison writing workshop; I’ve got one manuscript being considered at presses and another in the solid generating stages.

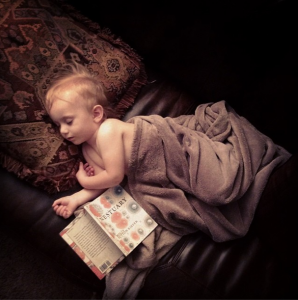

The most recent book, Nestuary, is a full-length lyric essay that examines these crucial shifts that happened in a small period of time—when I began to try to get pregnant despite an infertility condition (treatable with medication), when I was pregnant with my daughter and then son (oh, and how the son threw me for a little while in my feminist-brain! but how lovely for a feminist to raise a boy, yes?), birth—oh, birth!, and after. I find it astounding that a person can be so objectified when trying to shuffle through the medical complex. One thing I didn’t mention in the book was how my first appointment when I was pregnant with my son was with a doctor whose license plate read “PITOCIN” (this is what I’ve been told, I should say) and he was so terrible in trying to convince me to not even consider an attempted VBAC. “C’mon Moll,” he said. (Not my name.) “My wife did it three times! Easy, you’re in, the baby comes right out.” I wanted to write back against this, against the dismissiveness of so much of it, of the way society dictates this narrow image of what normal is: a white woman who has a blissful pregnancy, labors for a bit, births without much hitch, nurses, and becomes radiant-mama. Or becomes working-mama who can also make the dinner and tuck the kids in bed, no problem. She’s still wearing pantyhose. This image is so far from the truth, so far from experience. We all have our journeys and none of them are perfect. Nestuary is just the narrative of my own.

(Editor’s Note: See Sharon Kirsch’s review of Nestuary in TRIVIA: Voices of Feminism, Issue #16. Sharon is a past contributor to The Feminist Wire.)

Nestuary

Perhaps it’s that nothing went quite as planned. I was given the diagnosis of polycystic ovaries; I failed, and I fail, to ovulate.

You are meant to be a mother. Your body is designed for it. That is what this part of your body is for.

I felt as if a pincushion: blood tests, samplings for glucose levels, pregnancy tests and slow measure of medicine, morning temperatures taken with one wand, peeing-on-a-stick with another. There was the month I turned to acupuncture, stretched on my back, staring up at a rough-woven tapestry, my skin tingling at the site of perforation.

When I was pregnant, my fingers became pins, at least in the sense of tingling, I would lumber to the bathroom with a mild form of hyperemesis—a semblance of oxymoron, of course, hyperemesis being severe morning sickness—and there was the threat of another needle in my arm, that of the IV to replenish lost fluids. Instead, a daily purge and I’d toddle on. There was the restless legs syndrome, the odd feeling of bugs or lightning, in my elbow and shoulder, the bob in restaurants and constant insomnia.

I was a miserable pregnant woman, shocking my friends, who had pictured me as an Earth Mama, and told me so. Barefoot, fat and happy. My body was all wrong.

My Picasso Breast

i. the weeping woman

He loves her for the tick tick tick, the sweep

of knife on butcher-block, each webbed digit

flinchless. Her fingers are silverfish; they’ve played

the knife game before. Barren, she cannot know

the cut of child between her legs—

these stretched marks are not from cat’s paws.

Picasso tenderly draws her in, figure-eights her nose.

ii. decanting

Before bed, I shuck the seams

of the freezer-frozen milk bags.

They clatter into the sink like: poker chips,

struck bowling pins. In the morning,

I gut each bag, gill to sternum,

out comes the blue-tinge, the cream that rises.

My hands smell spoiled, the way they did

when the winter light was fierce

and we nested together against the snow.

iii. the dream

In it, a veiled figure stubbed a cigarette

onto my exposed breast, one smoosh

on the hard surface, smoothed-over doll’s proscenium,

self-tanned mound of plastic. I do not move.

If I move, you might be noticed. Harmed.

Burn craters, dollop of plastic rising out

like a drop in a pan of sauce. Droop and wither,

my body accommodates this change; even dreaming,

my body instinctively stills to keep you safe.

The Women Who Give Up Their Breasts

i Amazons

Art might alter it, the hollowing out of one left

hillock, just so the throwing is better, or an arm slung,

kept closer for speed. There, she leans, unbalanced

on horse, but never toppling, too superior in power,

her ballast tender, trilling, calling out names of the missing.

Did she sling her daughter on the same shoulder

as her quiver of arrows? Did she soothe sore fingers

in the O of her mouth, a tease from misknocked arrows?

Surely she’d carry her in the cavern left behind,

for safety, for weight of memory.

ii Nursing

The long arrow of pregnancy ended.

This is one beginning: the measure of clavicle to hip,

the bend of mother’s spine, the circle within a circle

that makes two a still lumpen whole.

My, it’s something that feels broken, that massive

watery fill, when away too long, let cabbage wings

leave the body smelling something of summer,

chopped delicately with carrots. Touched away

when the father reaches in: do you want to set it off again?

The waking in a puddle of one’s blue-white self,

this body that fed through a cord, feeds through a teat.

iii Saint Agata

Saint Agata swears nightly, her virginity belongs to God.

But being given to a brothel, unwrapped, found offering

two quivering breasts on a platter, silver-tipped

and still warm. Shaved off like a root vegetable. The artists

render a smallness that could never have been filled

and refilled like a feedbag. The voices of her attackers echo

in the chamberbox of her mind; unlocked, she doesn’t hear—

instead one long note, a long thread connecting her

to a god who has left her her body to retaliate.

iv Mastectomy

She wonders how it started, if it was like the tender grain

of sand, worried over time in the oyster’s maw. When did she

clamp shut like this? Where was her safe harbor?

She’ll never know where they go, the fillets of flesh

trimmed from her chest, the spilt-open-like-a-cake

as she lies trembling. Her convex will concave, she’ll touch

and retouch the scar, remembering the first

time they had been touched. She could replace them

with plastic sheaths, little fruits, cannons in synthetic bras.

She could fill with air, plump liquid gold.

v Breastbinding

There are historical markers: linen with embroidered crosses

from centuries-ago nuns, clatter of whale bone, remembrance

of Joan of Arc. She uses an Ace bandage, wrapping herself

in the dim light of morning, flesh knocking against flesh,

already small and uncut from puberty. This is how

she believes she is beautiful, by passing.

She calls them her lotus breasts, but doesn’t think

of feet, folded over like wings.

____________________________________

Molly Sutton Kiefer’s chapbook The Recent History of Middle Sand Lake won the 2010 Astounding Beauty Ruffian Press Poetry Award. Her second chapbook, City of Bears, was published in 2013 by dancing girl press. Nestuary was published in 2014. Her work has appeared in Harpur Palate, Women’s Studies Quarterly, WomenArts Quarterly, Berkeley Poetry Review, you are here, Gulf Stream, Cold Mountain Review, Southampton Review, and Permafrost, among others. She earned her MFA from the University of Minnesota, was selected for the Loft Literary Center’s Mentor Series, serves as poetry editor to Midway Journal, and runs Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts | An Interview Project. She currently lives in Red Wing with her husband, daughter, and newborn son, and is at work on a manuscript on (in)fertility. More can be found at mollysuttonkiefer.com.

Molly Sutton Kiefer’s chapbook The Recent History of Middle Sand Lake won the 2010 Astounding Beauty Ruffian Press Poetry Award. Her second chapbook, City of Bears, was published in 2013 by dancing girl press. Nestuary was published in 2014. Her work has appeared in Harpur Palate, Women’s Studies Quarterly, WomenArts Quarterly, Berkeley Poetry Review, you are here, Gulf Stream, Cold Mountain Review, Southampton Review, and Permafrost, among others. She earned her MFA from the University of Minnesota, was selected for the Loft Literary Center’s Mentor Series, serves as poetry editor to Midway Journal, and runs Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts | An Interview Project. She currently lives in Red Wing with her husband, daughter, and newborn son, and is at work on a manuscript on (in)fertility. More can be found at mollysuttonkiefer.com.

Pingback: Another feminist mama poet speaks truth, beautifully | Jennifer Givhan, Poet & Novelist