Personal is Political: Becoming a Black Gay Man: Activism, Identity, and Community-Building in the South

By Charles Stephens

Sometimes I wonder, often in despair and always with nostalgia, about the things that were once possible, things that no longer seem as possible. And of the things that were once possible, I think about this small window of history, a blink, a tiny opening that I was able to enter that transformed me. This period, from about 1999 until about 2002, signaled the end of what had been an extraordinary time in black gay men’s organizing and activism in Atlanta.

During this period, when the world was both falling apart and reassembling around us, black gay men also seemed to be both falling apart and reassembling. The Post-Protease era, the scientific advances in HIV drugs that helped people live longer, or really to live at all, was also the Post-Industrial era when the labor market changed, and already economically distressed communities became even more distressed. Affordable housing in Atlanta began to change or vanish, and some communities were displaced, moving to the suburbs and online, while others were being reborn and reinvigorated. Tony Daniels, the celebrated black gay activist had died a year before I came into community, and his death cast a shadow over everything like a spell that has yet to break.

In 1999, I was an 18-year-old first-year student at Morehouse College before transferring to Georgia State, the year I became involved in the activist community in Atlanta. It was the tail end of a decade defined by the urgency of black gay men facing death, daring to put everything into the proliferation of cultural work, organizing, and institution-building. The LGBT community had produced such dazzling victories, protesting a suburban anti-gay ordinance and thus keeping the Olympics out of Cobb County, being defiant in the face of the bombing of the Otherside Nightclub, 300 men at Second Sunday meetings, regular and well-attended readings at Speak Fire, building institutions left and right.

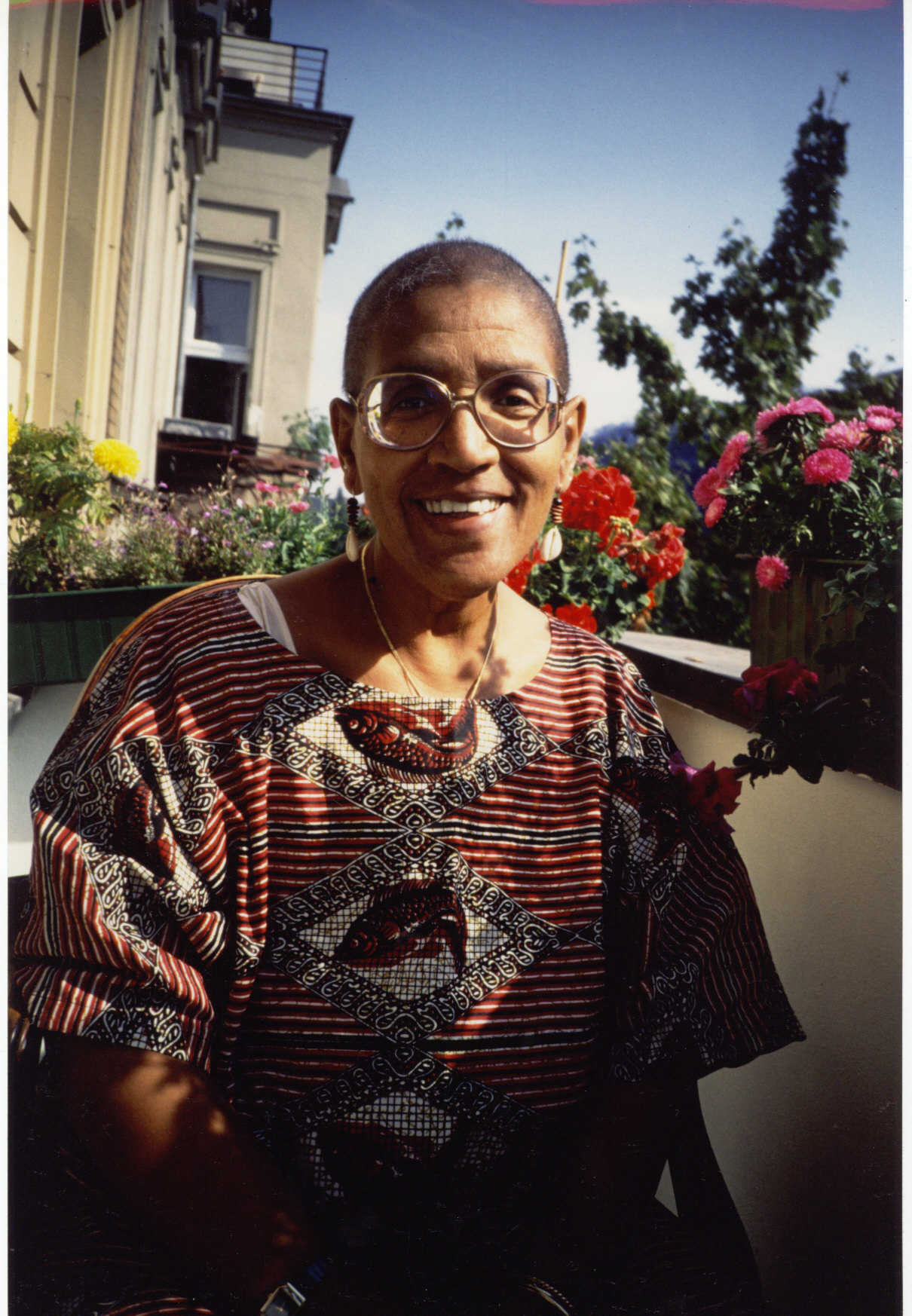

Another fact of history that did not occur to me until recently is the lineage of Feminist men in the leadership that helped contribute to the energy of those years. Many of the founding fathers were also Feminist and Queer fathers—people such as Craig Washington, Jafari Allen, Lance McCready, Duncan Teague, and Tony Daniels, among others that were influenced by Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, and Pat Parker. As a matter of fact, the first time I met Duncan Teague was at a Barbara Smith talk. They were poets and warriors, so I felt at home in their company as they ran around Atlanta spreading their magic. This was before HIV funding became as prevalent in the city, what others might call the “AIDS Industrial Complex” or the “Nonprofit Industrial Complex,” and the leaders changed, along with the political commitments. Academic credentials became a substitute for experience, wisdom, and creativity. I think the Deeper Love Project, a program I ran for many years, was the last hold out until it, too, changed.

We were products of our times, truly, our sensibilities forged by necessity and survival. Black queer men were dying like flies. So, I wonder what made such activism and community building possible then, but not in the same way now. The energy of the earlier time. The level of activity. The desire to explore on every level what it meant to be black and gay. The level of engagement. And the courage. What happened to groups like ADODI Muse, both the performance group and the writer’s collective, My Brothaz Keeper, Second Sunday, and SpeakFire? Hell, even the clubs seemed different. Places like Loretta’s, for example, always seemed, at least for black gay men, to be more of an institution than merely a bar. Or The Marquette, which was informally a rite of passage for many Morehouse College freshmen back in the day. By the time I came out, many of those groups were still around in some form, at their peak or having just passed their peak. This is where I am from. But now, the magic seems to be gone. A flame has gone out. The adventurous spirit of inventing ourselves seems to have been diminished.

One can only speculate as to the reasons why. HIV funding, for one thing, changed how community organizing happens. The fetishization of “numbers,” the representative of high-volume HIV testing, the cynical use of financial incentives to entice community members into engagement, and the social marketing campaigns seem to be more concerned with marketing than message. Of course, there was always dysfunction and trauma. Any oppressed person that dares to fight back will inevitably get hurt. Perhaps a lot of that trauma continued to impact our work, poisoning our efforts. We certainly turned on each other, but perhaps this happened one time too many. When did this generation of black gay men get time to grieve? Maybe they were too busy trying to survive. Nostalgia is a drug, so memory is distorted by sentimentality. But I cling to my sentimentality, because, in some ways, it fosters resilience. It helps me conquer cynicism. History may not be a romance, but what of memory?

And so I look back. I look back at the Midtown Train Station where you get off and go up the escalator on your way to a meeting of black gay men, maybe Second Sunday, maybe My Brothaz Keeper, with 30, 40, 50, or more black gay men engaged in discussion, love, shade, lust, and community-building. And exit, not on the Peachtree Street side but the other side, where the hustlers wear dingy t-shirts, if any shirt, and look you over to decide if you are worth approaching. The desperate ones will ignore your youth and your terror and approach you anyway. You don’t remember their words, only their gaze.

Though they are the ones selling it, you still feel like the merchandize. Masculinity has that effect. You are not gifted yet with the banter of your northern girlfriends, so performances of hypermasculinity, even on queer men, still shrink you. Your northern girlfriends seem to always be ready for a comeback, a witty remark, or a casual salacious comment, with blazing smiles and icy glares. As for you, you get lost in your thoughts. These men look too much like the ones that hunted you for sport only a few years earlier.

As his eyes search you, you grip the straps of your book bag tightly and walk away. In the time it takes to turn your head and look back, you will notice a car has already stopped, and he is standing at the window, leaning over, flashing the driver, or getting in. Or you may spy trade, in the corner of your eye, pissing on the side of the train station, or pretending to, ever ready to show his goods, holding his penis like a trophy. Sometimes you look back and see a police car stopping to ask him questions. But you keep moving. You have a group to get to.

Much later, you will realize that commercial sex teaches us something valuable about casual sex, that we are always purchasing and always selling. It is not the act of sex itself, but the desire that is transactional. Your social currency is your sexual currency. That’s why desire is the space where we learn that sexual choices and sexual freedom are not the same thing. In our consumerist culture, choice masquerades as freedom. The tragedy of neo-liberalism isn’t just the pervasiveness of corporations in public life, against a dwindling state, but the internalization and reproduction of those values in our intimate lives. The marketplace is not, then, an actual market after all, but a matrix—the emptiness that many of us feel at times, and the woundedness we cope with through consumption. The economies of desire for a lot of us are dystopian. Many of us learn too late, that being desired does not mean you will be loved.

It is getting dark as you make your way to West Peachtree Street. Just a few more steps. You are not afraid of being seen, but aware of being recognized, so you move like a thief, realizing that there is no other way to explain being in the middle of Midtown until you consider that anyone that catches you in the middle of Midtown is trying to find the same thing you’re looking for.

Finally, you approach the building, the Atlanta Lambda Center there on West Peachtree Street. Unassuming. Oh, the Atlanta Lambda Center! Another one of those places that can now only exist in the realm of imagination. A place that seemed to contain a lot of the wonderful activist energy of that era, as well as the activist trauma. Where groups met. Meetings held. Events planned. People gathered. People cruised. Shit got done. Shit did not get done. It’s in ruins now buried underneath some condo.

You walk in the lobby straight to the elevator. A few steps to the elevator and you’re on the second floor for the meeting. You arrive in the room. The chairs are already in a circle, and this is where it all starts. You are in a sea of unfamiliar familiar faces, all black and all male, and you scan the room for a smile. You are in the room where the parts of yourself, the black part and the gay part, find a home together, no longer rivaling for superiority. You are given back to yourself by the black gay men you encounter, and simultaneously ripped away from yourself, what you have known, who you were. All of this happens through the reading of the texts they introduce you too, by the discussions in which you participate, in the workshops you attend. Identity was not a secret, or a truth, or something deep within. It was always already a series of negotiations, a process, a dance, and ultimately a shield against a world. Of the many lines, moments, and epiphanies marking that era, the most critical one is when you went from being black and gay to being a black gay man, an important and necessary personal and political distinction. Not that such a consolidation of identities was a perfect moment, but all growth, even when it’s self-generated, is as painful as it is glorious.

_________________________________________________________

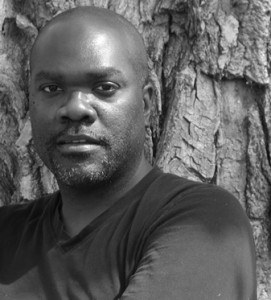

Charles Stephens is an Atlanta-based writer. His writing has appeared in Georgia Voice, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Huffington Post, Lambda Literary, The Gay & Lesbian Review, Alternet, and WireTap. Currently he is co-editing an anthology entitled Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call.

Charles Stephens is an Atlanta-based writer. His writing has appeared in Georgia Voice, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Huffington Post, Lambda Literary, The Gay & Lesbian Review, Alternet, and WireTap. Currently he is co-editing an anthology entitled Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call.

Pingback: My Latest on The Feminist Wire | Building Desire