Census Bureau Rethinks Ways To Measure Race

Possible revisions to how the decennial census asks questions about race and ethnicity have raised concerns among some groups that any changes could reduce their population count and thus weaken their electoral clout.

The Census Bureau is considering numerous changes to the 2020 survey in an effort to improve the responses of minorities and more accurately classify Latino, Asian, Middle Eastern and multiracial populations.

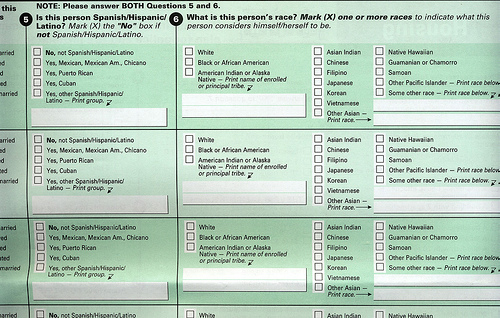

Potential options include eliminating the “Hispanic origin” question and combining it with the race question, new queries for people of Middle Eastern or North African heritage, and spaces for Asians to list their country of descent. One likely outcome could be an end to the use of “Negro.”

The stakes surrounding population counts are high. Race data collected in the census are used for many purposes, including enforcement of civil rights laws and monitoring of racial disparities in education, health and other areas.

In addition, the information is used to redraw state legislative and local school districts, and in the reapportioning of congressional seats. The strong Latino growth found in the 2010 census guaranteed additional seats in Congress for eight states.

Latino leaders say changing the Hispanic origin question could create confusion and lead some Latinos not to mark their ethnicity, shrinking the overall Hispanic numbers.

The wording in the 2010 census question, which asked people if they are of Latino origin and then provided a space to fill in their race, yielded a strong response and a record count of 50 million Latinos. Their growth moved them ahead of African-Americans as the nation’s largest minority group.

“We’re the only group in the country that has our own question? Why give it up?” says Angelo Falcon, director of the National Institute for Latino Policy. “A lot of Latino researchers like the question the way it is now because it shows those differences. The way the Census Bureau is thinking about combining the questions, it might take away that information in terms of how we fit within the American racial hierarchy.”

Falcon co-chairs a group of about 30 Latino civil rights and advocacy groups that recently met with the Census Bureau about the potential changes.

For many years, the accuracy of census data on some minorities has been questioned because many respondents don’t report being a member of one of the five official government racial categories: white, black or African-American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native and Pacific Islander.

When respondents don’t choose a race, the Census Bureau assigns them one, based on the racial makeup of their neighborhood, among other factors. The method leads to a less accurate count.

Broadly, the nation’s demographic shifts underscore the fact that many people, particularly Latinos and immigrants, don’t identify with the American concept of race.

The government categorizes Hispanic as an ethnicity, while many Hispanics think of it as a race. The confusion played out in the 2010 count, as nearly 22 million people — 97 percent of whom were Hispanic — identified as “some other race.” It ranked as the third-largest racial category.

In addition, Asians and Hispanics had the highest rates of interracial marriage in 2010. And 9 million people identified as multiracial, compared with nearly 6 million in 2000.

Even the terms “Latino” and “Hispanic” are met by many with ambivalence, according to a 2011 national survey by the Pew Hispanic Research Center. Only about 24 percent of adults use either term to most often describe themselves. Slightly more than half of the respondents preferred to identify themselves by their family’s country of origin. And 21 percent said they most often identify as American.

Middle Eastern and North African origin is an ancestry, which is no longer captured in the census form. The government racially defines the ancestry as white. Advocates say the methodology has led to the under-counting of people of Arab descent.

“We don’t necessarily identify as white because we have a lot of cultural and socioeconomic idiosyncrasies that are different,” says Samer Araabi of the Arab American Institute, which supports the Census Bureau’s efforts. “We think it’s a great step forward not only for the Arab-American community, but for all other communities that are currently being lost in the census form.”

The Census Bureau’s research for the 2020 form is based on findings from an experimental questionnaire sent to nearly 500,000 households during the 2010 census. The forms worded the race and ethnicity questions differently than the official form, including combining them as a single question. Census officials say the combined question led to improved response rates and accuracy.

Any recommended changes to the form must be approved by the Office of Management and Budget and by Congress.

0 comments