My Mother’s Body of Work

When I was eleven years old the Dance Theatre of Harlem came for the first time to Cincinnati, my hometown. Weeks leading up to the company’s arrival, I stared at the color photo of a black ballerina in a thin hardcover book about dancers around the world that someone had given to me as a birthday gift. Over the years of taking ballet classes where I was the only black girl, I was hungry for someone who looked like me, doing what I was trying to do in a world that found my body aesthetically illegible. So, from time to time I would open this book and turn to this page where I not only stared at the familiar beauty of this dancer, but wrote my name over and over again in big loopy curls along the perimeter of her body. The curves in the letters elongated as I got older. But, my name was always there encircling her like aura. I wanted to be there, too, captured by this photograph, but unlike the dancer, still able to alter the picture, make it change with me. When my mother found what I had done to the book she did not, as I anticipated, read me for defacing its pages. She simply said, “One day you’ll run out of space, maybe you should start thinking about bigger places to leave your mark.”

When I was eleven years old the Dance Theatre of Harlem came for the first time to Cincinnati, my hometown. Weeks leading up to the company’s arrival, I stared at the color photo of a black ballerina in a thin hardcover book about dancers around the world that someone had given to me as a birthday gift. Over the years of taking ballet classes where I was the only black girl, I was hungry for someone who looked like me, doing what I was trying to do in a world that found my body aesthetically illegible. So, from time to time I would open this book and turn to this page where I not only stared at the familiar beauty of this dancer, but wrote my name over and over again in big loopy curls along the perimeter of her body. The curves in the letters elongated as I got older. But, my name was always there encircling her like aura. I wanted to be there, too, captured by this photograph, but unlike the dancer, still able to alter the picture, make it change with me. When my mother found what I had done to the book she did not, as I anticipated, read me for defacing its pages. She simply said, “One day you’ll run out of space, maybe you should start thinking about bigger places to leave your mark.”

Although the woman in the photo was not a DTH dancer, she became the symbol for that company in my mind, second only to the company’s enigmatic founder, Arthur Mitchell. At eleven, I found Mitchell otherworldly. He might as well have fallen to earth from a spaceship in the sky as far as I was concerned. When I saw him walk down the aisle of the theater on the night of the company’s Cincinnati debut, I sensed my spirit leaving me to embrace him in a desperate bear hug while my body, leaden, weighted the seat. I think it was just at that viscerally confusing moment that my mother whispered in my ear, “Now’s your chance. Go up to him and introduce yourself!” I could have dismissed her, rolled my eyes and buried my face in the program – which is actually what I imagined I did until I realized my legs were already skimming past the people in the seats next to me, my heart racing as I made my way to Mr. Mitchell’s implausible elegance. At the same time that my mouth opened to say who knows what to this man, the lights in the theater dimmed and the intermission bells cautioned us to find our seats. Mr. Mitchell turned to look at me and, to this day, I still imagine him thinking the warning chimes emanated from my gaping mouth. What happens next gets kind of blurry, primarily because I have strategically employed shadows in memory to soften my profound embarrassment. Nonetheless, there was some exchange between us where the unfortunate combination of my incoherence, the 3-minute warning, and the other much more important matters waiting for him at the end of the aisle ended in my unceremonious dismissal. Oh, and I think I may have also reached out to touch him since I vaguely remember standing frozen with extended hand. It felt as if the entire audience was burning a hole in the back of my head with their hot glares. Who accosts Arthur Mitchell and then, dumbstruck, blocks his path on his opening night? I sunk back into the scratchiness of the old velvet fabric melting deeper into the chair, my mother poking me, still excited… “Well, maybe next time. At least he knows your face now. You should be proud of yourself.” I think of this story most often when I stop to think about my mother and the imprint her courageously independent ethos has tried to leave on me. I say “try” because I am still working to believe deep in my bones, rather than superficially perform, her innate, for lack of a better word, “self-optimism.” My mother is fierce. Not in the old-school, high drama, mean-spirited vein of a Dominique Deveraux, but with a determination and generosity that inspires everyone around her to think and act bigger. My mother taught me to ask for what I want and to demand what I need, and always reminded me that whether that thing comes to you or not matters less than cultivating your ability to acknowledge and honor your desires. I also frequently think of this story because it is where two of the greatest loves and challenges in my life, my mother and dance, meet at their most awkward intersection.

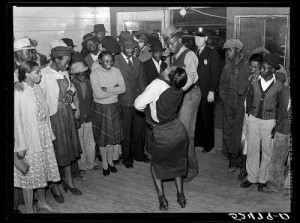

My mother, Mary Elizabeth Wallace, was the tenth of eleven children raised by my grandmother after my grandfather passed when my mother was three. She grew up in Clarksburg, West Virginia with nine sisters and one brother who showed her how to be in the world in ways that would allow her to protect and free herself at the same time – not easily accomplished for black women coming of age in the 1940s and 50s. These were women who left West Virginia at seventeen on buses headed to New York City to make money for college by cleaning hotels and houses over the summer, while falling without fanfare or dramatic proclamation, into organizing for labor rights. These were women, my aunties, who moved to cities like Washington, DC and Cincinnati, Ohio to ostensibly teach, nurse and administrate in some of the only official roles open to them, while building community in the most invisible and vital spaces that sustain life. During this time, and arguably even now, implied and explicitly rigid rules around the norms of presentation and behavior for black women attempted to restrict the ways my mother and her sisters could work, walk, dress, speak, create things of beauty and love. In spite of the way the social, political and economic conspired to limit the possibilities for who she could even imagine becoming, my mother emerged as herself – fully, unapologetically. This, is what I am still learning how to learn from my mother in the lessons that she teaches me through her body and, literally, her movement through the world.

My mother, Mary Elizabeth Wallace, was the tenth of eleven children raised by my grandmother after my grandfather passed when my mother was three. She grew up in Clarksburg, West Virginia with nine sisters and one brother who showed her how to be in the world in ways that would allow her to protect and free herself at the same time – not easily accomplished for black women coming of age in the 1940s and 50s. These were women who left West Virginia at seventeen on buses headed to New York City to make money for college by cleaning hotels and houses over the summer, while falling without fanfare or dramatic proclamation, into organizing for labor rights. These were women, my aunties, who moved to cities like Washington, DC and Cincinnati, Ohio to ostensibly teach, nurse and administrate in some of the only official roles open to them, while building community in the most invisible and vital spaces that sustain life. During this time, and arguably even now, implied and explicitly rigid rules around the norms of presentation and behavior for black women attempted to restrict the ways my mother and her sisters could work, walk, dress, speak, create things of beauty and love. In spite of the way the social, political and economic conspired to limit the possibilities for who she could even imagine becoming, my mother emerged as herself – fully, unapologetically. This, is what I am still learning how to learn from my mother in the lessons that she teaches me through her body and, literally, her movement through the world.

I knew from early on that in most of the spaces I occupied I was a problem, or more specifically, that my body was an issue. This was most apparent in the small, dysfunction-inducing realm of classical ballet in the Midwest. I was a dark skinned black girl, curvy and visibly strong and, despite the fact that I had talent, at every turn I was made to feel as if I was trespassing on sacred ground. My body nor my personality (on stage or in real life) were transferrable to the distressed damsel or fragile swan. The self-consciousness I was made to feel was totally at odds with what I saw in my home and in the way my mother owned the beauty of her body. She was an athlete and still is at 71, and is always more interested in what her or any other body is capable of doing, offering and expressing than what it looks like. Her privileging of the body’s physical and emotive strength over its subjective visual appeal, is what has centered me as a dancer and, perhaps most importantly, grounded and guided me as a grown woman.

In the summer she lived in swimsuits, planting vegetables and working in our yard nearly bare except for the rich soil and deep grasses that covered her. Meanwhile, I hid my teenage self, primarily from myself, in clothes that might allow me to forget my body. It is difficult to say when the shift occurred, but at some point in my late twenties years after I began dancing professionally, I finally learned how to like my body and love myself enough to listen to all of the things by body and the intuitive energies it housed had to tell me. In this shift, I felt the connection I had not really understood before between my mother’s determined attending to her needs and her ease in her own skin. More than a self-love, her acceptance of herself (starting but not ending with her body) makes space for her to envision and enact how she can live fuller, more purposefully and humanely and, thus, create the conditions whereby others might be able to do the same.

But how does this miracle of holding onto yourself happen for a black woman who came to an ultra-conservative city like Cincinnati, Ohio during the last years of the Great Migration? And how do you pass that on to your daughters? I believe there is something about the continual day-to-day confrontation with your socially constructed devaluation that can destroy you or inspire the terms of your self-defined creation. The majority of black women, if they are able to exert the luxury of choice, move to the latter place of self-making. And, in many ways, it makes sense that our bodies, the sites where the violence of our subjugation plays out, is where we first loose and then ultimately find ourselves. I love, am inspired by and live through my mother for countless reasons, but felt compelled today to speak about her body and the courage I’ve gained from witnessing the sublime joy she has found in her own physicality. This is the joy that supported my eleven-year old desire to see my name wrapped around a body that would be the closest thing I would come to seeing myself in a text until I entered college and devoured the images created by the words of Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Angela Davis and Cherrie Moraga. This is the joy that propelled me out of my seat to speak to a man who saw the beauty in black dancing bodies, and the joy that convinced me that his response shrunk in comparison to my newfound belief that I was entitled to speak. This is the joy that moved me across stages dancing the stories I was otherwise too afraid to tell. This is the joy that fuels my artistic projects with young women of color wanting to write their names at the center of their own texts. This is the joy that reminds me to only offer my love if I am strong enough to have it rejected, and this is the joy that forces me to love without second thought or regret, despite these rejections. This is the joy of my life. Mom, thank you for showing me how to live in and beyond my body. I love you.

0 comments