Why Ethnic Studies Matters

By Arizona Ethnic Studies Network

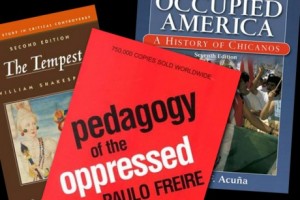

On February 29, 2012, members of the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network held a Read-in at Wesley Bolin Plaza across from the Arizona State Capitol. The “National Read-in Day “ was organized to bring attention to the dismantling of the Mexican American Studies Program (MAS) in Tucson high schools and the subsequent banning of a variety of books from use in classrooms.

The banning of books and closure of the MAS program was the direct result of the Arizona Legislature’s passage of HB 2281, which declared that “public school pupils should be taught to treat and value each other as individuals and not to be taught to resent or hate other races or classes of people.” The bill allows the state superintendent of instruction or the state board of education to eliminate any classes that were found to: “1. Promote the overthrow of the United States government. 2. Promote resentment toward a race or class or people. 3. Are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group. 4. Advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.”

The Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) board voted to shut down the program after State Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal threatened to eliminate $15 million dollars in state funding for the district’s budget if they continued to offer the program. Huppenthal and an administrative law judge decided that the MAS program violated Arizona statutes and the district was ordered to pack up the books and hold them in a depository. Because the books are formally prohibited from classroom use (teachers and students report that monitors have been assigned by TUSD to guarantee they are not being taught), the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network considers this action a de facto ban of books.

The Arizona Ethnic Studies Network believes that the responsibility for the closure of MAS, then, was the result of an ideologically-inspired bill that sought to undermine Ethnic Studies as a legitimate and valuable part of public education, as well as an equally misinformed decision by Huppenthal – who rejected an independent audit that he commissioned that found no violations of the law–and a school board that did not support the MAS program.

Arizona educators organized AESN in January to speak out against HB 2281, support the MAS program, and to counter the overwhelmingly negative and distorted opinions about Ethnic Studies. Tucson high school students organized their own group, UNIDOS, in order to defend MAS and have since been making appearances nationally via Skype to share their experiences with many college classes and campuses. A group called Save Ethnic Studies, representing teachers, students and community activists, is pursuing legal action in the federal courts. The AZ Ethnic Studies Network seeks to educate the public about what Ethnic Studies is and why it is vital to education and for the state’s future.

Over the course of the day on February 29th, thirty volunteers from local high schools, community organizations, and ASU read aloud passages from several of the banned books to an audience that totaled close to 90 people throughout the day –some simply passing through the park, but most coming to show their support for the history and experiences conveyed by the books of a more diverse and inclusive American society.

The read-in commenced with a press conference with Karen J. Leong, a faculty member at Arizona State University in Women and Gender Studies and Asian Pacific American Studies, and two graduate students in the Justice and Social Inquiry Program at ASU, Meghan McDowell and Grace Alvarado. Press coverage was extensive.

Leong explained that she taught Ethnic Studies content in her classes in order to provide students with a more complete picture of United States history and contemporary society today. She emphasized how, in a globalizing, diverse society, Ethnic Studies teaches students to ask questions and seek answers beyond what is simply presented as fact and to look beyond the accepted dominant narrative.

Alvarado spoke about her own experience in the MAS classroom in Tucson as a student teacher, and noted that the MAS teachers never advocated hatred nor the overthrow of the US government. Alvarado observed that the MAS teachers, “are among the most dedicated and talented professionals I have encountered. … As an adjunct instructor at the University of Arizona, I had the privilege of teaching students that had gone through the MAS program. By and large these students outpaced their peers in their ability to critically engage with history and current social issues and communicate their analyses concisely. These are invaluable skills that serve all students.”

McDowell shared the impact Ethnic Studies had upon her own education: “I grew up in a rural, predominately white agricultural community in northwestern Vermont. This meant that I was not taught about Cesar Chavez, Ella Baker, W.E.B Du Bois, or the American Indian Movement. Instead, I learned about these individuals and the movements they were a part of in ethnic studies classes. These classes did not teach me to hate myself for being white. These classes taught me to advocate for a society that treats all people with dignity, mutual respect, and openness to personal and institutional transformation.”

Author Stella Pope Duarte, the first reader of the day, prefaced her reading by sharing her perspective as an author whose own book, Let Their Spirits Dance, had been taught as part of the MAS program. She had been a yearly guest speaker at the Tucson high schools, where she would speak about her novel — in which she traces the journey of a dying Latina to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC to honor the memory of her son who died in the war thirty years ago. She would discuss with students the universal themes of loss, grief, memory, and war, as well as the specific experiences of Latino and Latina soldiers in the Vietnam War.

“It breaks my heart!” she exclaimed, that this was the last year she would meet with the Tucson high school students— she was informed that she would no longer be invited to the classroom after this year.

These opening statements challenged the distorted ideas circulating about Ethnic Studies and asserted that Ethnic Studies is valuable for all students regardless of ethnicity. There are undoubtedly lessons specific to each students’ background – learning about a community from the perspective of the members of that community may encourage critical analysis of dominant assumptions based on one’s class, race, gender, sexuality, or nationality; understanding how diverse communities’ histories are part of a national history has been shown to contribute to students from those particular communities increasing their engagement in the classroom and improving their academic achievement. Yet there also are shared benefits in teaching these texts in the classrooms. The different responses students may share to a common text helps to reveal the very process by which social location contributes to diverse experiences of US history and American society, and challenges students to consider how American society values or devalues difference and why.

Individual volunteers also shared why they participated in the read-in. Several educators and community members spoke of the moment of recognition that transformed their own self-perception and heightened their critical consciousness—a process described by Paolo Freire (whose Pedagogy of the Oppressed was one of the books receiving the most criticism from Huppenthal) as conscientization.

One Pacific Islander woman who grew up in the Marshall Islands shared how she recognized the very first lines of Sherman Alexie’s Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven “as my own story.” Another Latina faculty member shared how reading Sandra Cisneros’ House on Mango Street gave her a point of identification from which to locate herself in the United States. It was as simple as recognizing the distinctions of hair and fashion within her own community and the experience of recognizing oneself in a classroom text that inspired her desire to learn more—and not just about Latino culture and history, but about the diversity of experiences that constituted the society around her.

Some readers participated in honor of others. ASEN member and ASU English faculty member Lee Bebout prefaced his reading from Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway by explaining that his interest in Chicana/o Studies began when he taught high school ESL and English in Texas, where his students were primarily Mexican or of Mexican descent.

“Those classes and those students taught me so much. … Reading Urrea’s work today is a way of honoring my roots in the field of Chicana/o studies, for my students and their families were not too different from those men [in Devil’s Highway] …. . Attacks on immigrants are often proxies for those on people of color. Attacks on the rights of people of color are likewise framed in terms of cultural takeover of (white) America.”

Donna Cheung, a community member, reading from Ronald Takaki’s A Different Mirror, explained that she migrated to the United States when she was five years old. “The circumstances that brought me here began many years ago when my parents, grandparents, and aunts and uncles decided that it was better to face a future of uncertainty than to live under a communist regime that told everyone what to believe and what to read. Today …in the State of Arizona, we are faced with a smaller regime that is telling us what to think and what to read; I read today to honor my parents.”

During the read-in, network members also met with state legislators to explain the purpose of the read-in and advocate for ethnic studies. Representative David Lujan participated by reading from Jonathan Kozol’s Savage Inequalities, and other legislators stopped by to show their support. Representative Sally Gonzales had requested acknowledgement of the read-in on the floor of the house, and Representative Albert Hale spoke about his attempts to establish Native American Studies programs.

Educators and students across the nation also organized their own events in support of the Read-In and Ethnic Studies in Arizona. Student centers at University of Texas at Austin, Georgetown University, Duke University, and University of Montana at Billings, graduate students at SUNY Stonybrook and UC Berkeley, and faculty and staff at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Western Washington University, University of St. Thomas, Michigan State University, Colorado College, and Mary Baldwin College, all organized events for February 29.

The read-in introduced the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network to the state, and evidenced support for Ethnic Studies on the part of educators and community members. The ACLU sponsored an hour of the read-in and developed its own webpage about the banned books; Arizona Teachers for Justice, consisting of K-12 educators, closed the read-in with teachers speaking about their own experiences teaching about diversity and social justice in the classroom. These organizations look forward to continued collaborations that promote Ethnic Studies statewide.

It is telling that these books – seen by some with institutional power as threatening dominant narratives of US democracy- brought together a disparate and ethnically diverse group of individuals who, in the process of sharing their own experiences and histories, created a community based on a shared commitment to the transformative power of critical knowledge and social justice.

For more information about the network, please see azethnicstudies.com.

_______________________________________________

This article was written by Karen J. Leong on behalf of the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network. Dr. Leong is associate professor of Women and Gender Studies and Asian Pacific American Studies in the School of Social Transformation, and affiliate faculty of History and Film and Media Studies at Arizona State University. Her scholarship focuses on intersections of gender, race, and nation, particularly in relation to United States and Asian American history. She is author of The China Mystique: Pearl S. Buck, Anna May Wong, Mayling Soon, and the Transformation of American Orientalism, published in 2005 by University of California Press, as well as numerous articles.

This article was written by Karen J. Leong on behalf of the Arizona Ethnic Studies Network. Dr. Leong is associate professor of Women and Gender Studies and Asian Pacific American Studies in the School of Social Transformation, and affiliate faculty of History and Film and Media Studies at Arizona State University. Her scholarship focuses on intersections of gender, race, and nation, particularly in relation to United States and Asian American history. She is author of The China Mystique: Pearl S. Buck, Anna May Wong, Mayling Soon, and the Transformation of American Orientalism, published in 2005 by University of California Press, as well as numerous articles.

Pingback: Why Ethnic Studies Matters | The Feminist Wire | Arizona Ethnic Studies Network

Pingback: Why Ethnic Studies Matters | The Feminist Wire | Arizona Ethnic Studies Network

Pingback: Why Ethnic Studies Matters | The Feminist Wire | Arizona Ethnic Studies Network

Pingback: Why Ethnic Studies Matters | The Feminist Wire | Arizona Ethnic Studies Network

Pingback: Current Events In Europe | Living History

Pingback: Current Events In Europe | Living History

Pingback: Current Events In Europe | Living History

Pingback: Current Events In Europe | Living History