‘Schoolin’ Life’: Teaching Beyoncé and Engaging Youth

Editors note: Just recently, several media outlets took to their cyber-phones, and began parsing what it meant for a cultural icon like Beyoncé to enter academe. Well, not “enter” in a traditional sense, as a student crosses the threshold from high school into the university system, but “enter” as a site of critical inquiry, knowledge and criticism. As a black feminist cultural critic with a range of views on the stars’ multi-layered performances, both on and off stage, and perhaps both consciously and unconsciously, I found the idea of ‘teaching Beyoncé,’ particularly in a feminist context, quite fascinating. (No, not “revolutionary.” Fascinating–as in intriguing). However, I found many of the media analyses wanting. In short, I wanted a little more. So, I decided to reach out to the source, Mr. Kevin Allred, and get his spin on why “Feminist Perspectives: Politicizing Beyoncé” should matter. Enjoy! — Tamura A. Lomax

By Kevin Allred

In Fall 2010, I created and taught a course entitled “Feminist Perspectives: Politicizing Beyoncé.” Even though the class has officially wrapped, word has spread over the internet just recently, with many arguing that such a course is a waste of time and money, as if grades are earned based on the amount of Beyoncé trivia one knows or how much choreography gets memorized. It’s a sad state of affairs when the critical thinking skills necessary for young people to navigate the world around them and understand and empathize with the lived political realities of race, gender, sexuality and class in the U.S. are no longer seen as worthy components of a comprehensive education in our contemporary corporatized university industrial complex society. Today’s educational system prides itself on rote memorization of facts at the expense of rearing informed, decent human beings.

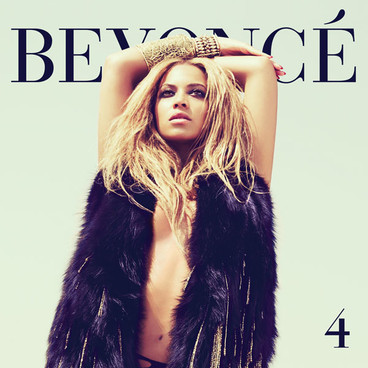

In a bonus track for the deluxe edition of Beyoncé’s most recent album, 4, she chants, “Who needs a degree when you’re schoolin’ life?” While “Schoolin’ Life” is a fun, upbeat jam with lyrics alluding to seizing/living in the moment and resisting growing up at too young an age (presumably autobiographically referencing the early onset of fame and celebrity Beyoncé herself experienced), the song also serves as a tongue-in-cheek reference to the fact that Beyoncé never attended college but now dominates our pop culture lexicon and has become one of the world’s biggest superstars anyway. In recent debates and criticism over the worthiness on Beyoncé, I fear the above lyric has also been seriously misinterpreted to either privilege life experience over education or to privilege education over life experience. What my hope for the class was and still is, is that it refuses to do either, as the young people in my classroom (a group that I am not far removed from myself), especially marginalized groups like young women, people of color, and LGBTQ folks, have become both increasingly angered and alienated from stuffy college classroom lectures that seem to have no practical applicability to their lives. In fact, Beyoncé herself references this contradiction in the song by stating, “I’m not a teacher but I can teach you something.” Indeed, I think she can—and it’s not at all what critics would have you believe.

Beyoncé Knowles is known as many things: singer, songwriter, actress, diva, performer, half of pop culture’s most powerful couple, even fashion designer. But, few take her seriously as a political figure. My course attempts to think about contemporary U.S. society and its current class, race, gender, and sexual politics through the music and career of Beyoncé. On the surface, she might deploy messages about race, gender, class, and sexuality that appear conservative in relation to social norms, but during the course I asked: how does Beyoncé push the boundaries of these very categories to make space for and embrace other perhaps more deviant bodies, desires, and/or politics? I attempt to position Beyoncé as a progressive, feminist, and even queer figure through close examination of her music alongside classic black feminist readings on political issues, both contemporary and historical. I wanted to put Beyoncé’s music in conversation with these texts in order to look at the ways in which she, along with other related black female musicians, politicize the black female experience in the U.S. and challenge/complicate society’s normative conceptions of what it means to be a black woman.

For instance, when listened to in conjunction with the experience of Sarah Baartman (dubbed the Venus Hottentot), what does “Bootylicious” by Destiny’s Child tell us about the ways perceptions of black women’s bodies have changed and/or stayed the same over the years? While observing what bell hooks’s assertions in “Killing Rage,” or the ways that Audre Lorde utilizes anger as a creative, political force, how might the songs “Resentment” and “Why Don’t You Love Me?” exhibit what I have termed Beyoncé’s own “politics of resentment;” a kind of political complaint directed towards the U.S. state for its continued failure to address the needs of black women in particular. How can reading Cheryl Clarke’s “Lesbianism: An Act of Resistance” shed new light on the compulsive heterosexuality that materializes in songs like “Scared of Lonely” or “Broken Hearted Girl,” while also emphasizing that compulsive heterosexuality in many of Beyoncé’s songs fails miserably? When read against the passage and/or prohibition of same-sex marriage in states across the country and in the wake of the Proposition 8 debacle in California, what does “Single Ladies” say about who is allowed to put a ring on what? Additionally, the controversy sparked by that video over whether the dancers were biologically male or female, calls into question who a single “lady” even is or can be. The important thing is not to answer the question, but rather the impulse behind the public’s need to have gender lines so clearly delineated.

Since teaching the class initially, Beyoncé has put out a new album, 4; been criticized for both the lightening of her skin in one photo shoot and taking pictures in blackface in another; and perhaps most famously, becoming a new mother. Part of the difficultly, but also the inherent fun, of working with a living, breathing text in the college classroom is the constant need to reevaluate and reshape the syllabus to reflect new developments. When teaching this course again, I would hope to engage with the sonic quality of Beyoncé’s voice on 4, which falls in line more with traditional soul singing, as well as the genre’s history of protest, than anything she has previously released. I would also investigate the diverse sampling credits on 4, including Nigerian musician Fela Kuti in the song “End of Time.” I would like to push students to think about what is being said about race in a photo spread utilizing blackface, and why, while claiming that race is not a factor for her as an artist, she would engage with such a politically fraught practice. I would love to interrogate the obsession the public has with Blue Ivy, Beyoncé as a mother, and her newly formed stereotypically heterosexist nuclear family unit, especially in relation to the controversy over the false accusations that Jay-Z would no longer be using the word “bitch” in his music out of respect for his new daughter. Why did we desperately want this to be true? Do we believe it speaks to an end to sexism? As if the word itself was the problem, and not the underlying systems of oppression and domination that the U.S. still fails to recognize in many ways.

So I say, you may not be a teacher in the traditional sense Beyoncé, but it’s time to move beyond old-fashioned conceptions of what makes a teacher and what constitutes a student. Every semester, I learn as much from my students as I hope they take from me. And I hope at the end of the day, all my students remember our class as a moment in time that challenged them and made them see the world differently. Like Beyoncé on 4, I hope each of them looks back at the class and is able to say, “I was here.” And that being present was, and is, important.

___________________________________

Kevin Allred has a Bachelor’s degree from Utah State University and a Master’s degree from UMass Boston, both in American Studies. He has taught extensively in Women’s and Gender Studies and American Studies at Rutgers University, including his own signature course: Feminist Perspectives: Politicizing Beyoncé. Currently, he is working on a dissertation interrogating U.S. black feminism through the sonic register, attempting to politicize the very sounds black women’s voices make, both live and recorded. He is particularly interested in the ways black female musicians – like Nina Simone, Odetta, Beyoncé Knowles, Nicki Minaj, and Janelle Monáe – manipulate their voices in such a way that histories get sonically recapitulated and transformed into a form of sonic warfare against the state. He has been politically active with national and local LGBTQ organizations over the past thirteen years working on issues of queer youth empowerment through music, as well as nationally touring as a singer/songwriter and releasing two albums on his own independent record label, Gutter Folk Records. At present, he is at work on a third album of original songs and teaching in the American Studies department at UMass Boston.

Kevin Allred has a Bachelor’s degree from Utah State University and a Master’s degree from UMass Boston, both in American Studies. He has taught extensively in Women’s and Gender Studies and American Studies at Rutgers University, including his own signature course: Feminist Perspectives: Politicizing Beyoncé. Currently, he is working on a dissertation interrogating U.S. black feminism through the sonic register, attempting to politicize the very sounds black women’s voices make, both live and recorded. He is particularly interested in the ways black female musicians – like Nina Simone, Odetta, Beyoncé Knowles, Nicki Minaj, and Janelle Monáe – manipulate their voices in such a way that histories get sonically recapitulated and transformed into a form of sonic warfare against the state. He has been politically active with national and local LGBTQ organizations over the past thirteen years working on issues of queer youth empowerment through music, as well as nationally touring as a singer/songwriter and releasing two albums on his own independent record label, Gutter Folk Records. At present, he is at work on a third album of original songs and teaching in the American Studies department at UMass Boston.

4 Comments