Black Power and Its Afterlives: A Conversation With Historian Ashley D. Farmer

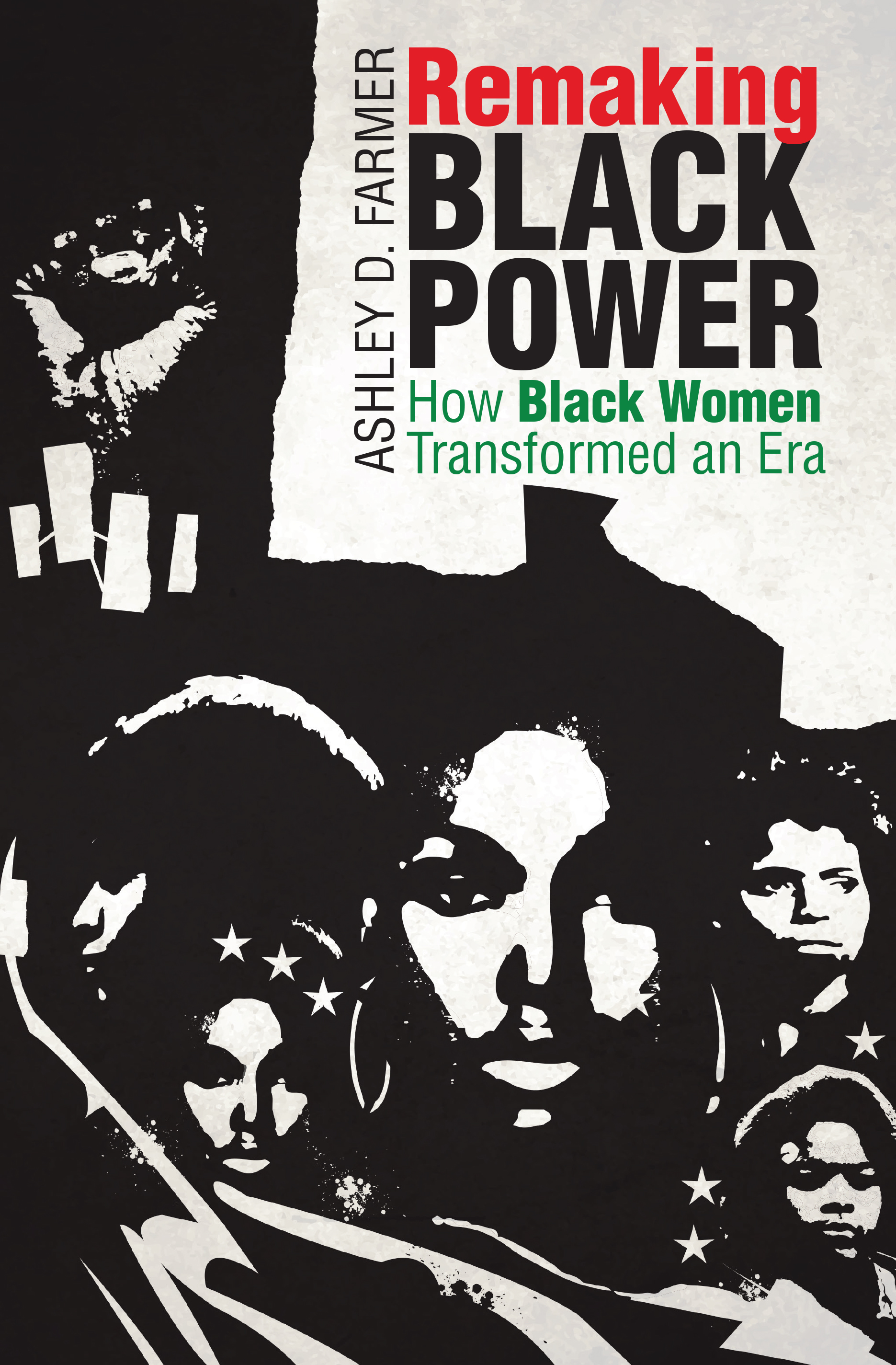

I had the pleasure of speaking with Professor Ashley D. Farmer about her field-defining new book Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (UNC Press, 2017). Farmer is a historian of black women’s history, intellectual history, and radical politics. She is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of History and the African American Studies Program at Boston University. Farmer’s scholarship has appeared in numerous venues including The Black Scholar and The Journal of African American History. She has also contributed to popular outlets like The Independent and the History Channel. She is also a leader in the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) and a regular blogger for Black Perspectives. Farmer earned her BA from Spelman College and a PhD in African American Studies from Harvard University.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Professor Ashley D. Farmer about her field-defining new book Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (UNC Press, 2017). Farmer is a historian of black women’s history, intellectual history, and radical politics. She is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of History and the African American Studies Program at Boston University. Farmer’s scholarship has appeared in numerous venues including The Black Scholar and The Journal of African American History. She has also contributed to popular outlets like The Independent and the History Channel. She is also a leader in the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS) and a regular blogger for Black Perspectives. Farmer earned her BA from Spelman College and a PhD in African American Studies from Harvard University.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Remaking Black Power is the first comprehensive study of black women’s intellectual production and activism in the Black Power era. Complicating the assumption that sexism relegated black women to the margins of the movement, Farmer demonstrates how female activists fought for more inclusive understandings of Black Power and social justice by developing new ideas about black womanhood. This compelling book shows how the new tropes of womanhood that they created–the “Militant Black Domestic,” the “Revolutionary Black

Woman,” and the “Third World Woman,” for instance–spurred debate among activists over the importance of women and gender to Black Power organizing, causing many of the era’s organizations and leaders to critique patriarchy and support gender equality. Making use of a vast and untapped array of black women’s artwork, political cartoons, manifestos, and political essays that they produced as members of groups such as the Black Panther Party and the Congress of African People, Farmer reveals how black women activists reimagined black womanhood, challenged sexism, and redefined the meaning of race, gender, and identity in American life.

_________________________________________________________________________________

TFW: I enjoyed reading Remaking Black Power. You draw from such a rich archive. What was the one piece of evidence—if you had to choose only one thing—you discovered that compelled you to write this book?

ADF: As I was looking through microfilm of the Committee for Unified Newark, I found a text called the “Nationalist Woman” handbook. As I scrolled through this handbook, I saw how women who practiced cultural nationalism were redefining what it meant to be a woman and a follower of Kawaida, a political ideology that argued that black-centered cultural practices were the first step to black liberation. The fact that I found this document was important for two reasons. First, cultural nationalist or Kawaidist organizations had a reputation for being extremely sexist and oppressive toward women. Second, it was a great example of how women in these organizations articulated their understandings of what it meant to be a woman and an adherent to a particular political philosophy. This convinced me that despite popular and scholarly ideas about Black Power sexism, I could not only write a book about women’s roles in the movement, I could also write one that centered their intellectual production.

TFW: You center your argument on what scholars have termed the “gendered imaginary.” Why is this a vital framework through which to study black women’s fight for Black Power?

ADF: The Black Power era was a moment in which activists were invested in redefining what it meant to be black and free outside of white norms and values. An important but often overlooked component of these discussions is how they redefined black womanhood and manhood. The book examines what many scholars have called the “gendered imaginary” or activists’ idealized, public projections of black womanhood or manhood. In other words, their writings and drawings about how they thought black women should behave, organize, dress, act, etc. in order to embody or enact black liberation. In the book, I argue that black women used visual art, literature, and political tracts to redefine black womanhood and to critique conservative ideas of their activist and intellectual roles. As a result, the gender imaginary becomes an important space to think about how black women interpreted and enacted black power.

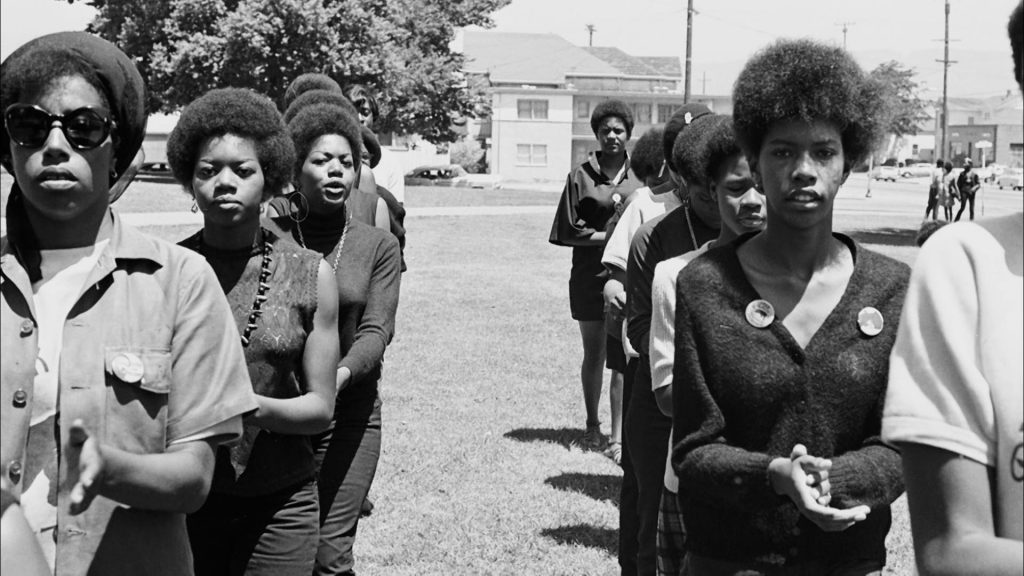

TFW: Why does the image of the gun-toting, male Black Power revolutionary loom large in the American imaginary? How do we as historians complicate this perception of the movement?

ADF: I think that this narrative of the male, gun-toting militant is, in part, due to the way in which the media documented the movement at the time. However, in the movement’s afterlife, it has become a way to marginalize Black Power actors and their ideals, rather than take them seriously as political, social and cultural organizers. As historians and students of this period, we can complicate this narrative by diversifying the range of actors, writers, and thinkers that we examine, complicating our ideas of what constituted a “success” or “failure” within the movement, and broadening the range of sources that we analyze. Exploring black women’s definitions of womanhood and liberation during the Black Power era is a way to enact all three of these suggestions.

TFW: I have a newfound love of the work of visual artists Gayle Dickson and Tarika Lewis! You situate them within a genealogy of black women political thinkers and cultural producers. How does your book contribute to and/or complicate the historiographies of the Black Power movement and the Black Arts movement?

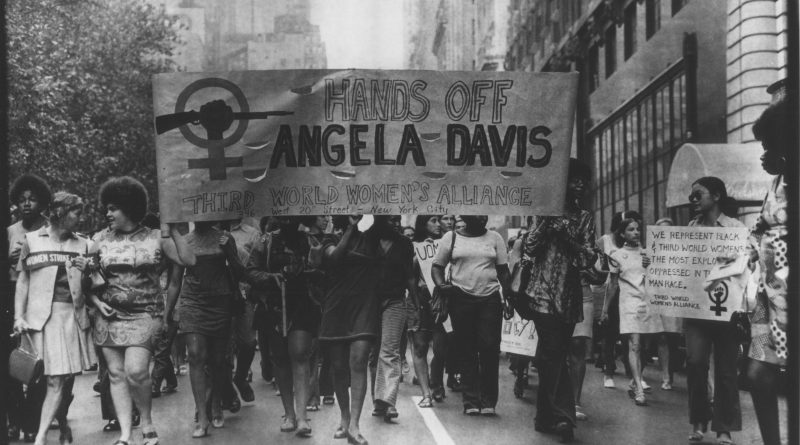

ADF: There are several moments in the book in which black women’s visual production comes to the fore. Dickson’s and Lewis’ “Revolutionary Art” for the Black Panther Party is one example. Another is the drawings and mixed-media images of women that members of the Third World Women’s Alliance, a Black Power feminist group, produced. I see this artistic production as examples of when black women were shaping the gendered imaginary in favor of their ideals of their roles and liberation. In the process, they contributed to a vibrant Black Arts scene, or the black-centered collection of art, poetry, music and writing that emerged during the 1960s and 1970s. In including these images, I hope that readers see that black women contributed to both the Black Arts and Black Power movements, that they did so in both well and lesser-known ways, and that they viewed art as a critical medium through which to share their ideas.

TFW: Several years ago, I was chatting with my black feminist mother, and she said, “I didn’t know Tupac was Afeni Shakur’s son.” And I told her that I’d just recently learned that ‘Pac’s mom was a Panther. We laughed about our different cultural-political connections to the Shakurs. What kind of cross generational conversations do you want your book to inspire?

ADF: This is a great question. I hope the book leaves readers with the impression that this is both recent and relevant history. Because it is recent, we have the wonderful opportunity to be able to speak with those women who were a part of the movement and those who grew up under them. Many of them are very eager to impart their experiences on younger generations. I hope that this book will encourage readers to seek out and spend time with the freedom fighters they have learned about and those in their communities and speak with them about their successes and failures and what lessons they learned that can be relevant to activism today.

2 Comments