Agnes Martin and the Necessary Joy in Opting Out

In 1967, Agnes Martin left New York. She bounced around the country, landing in New Mexico where she built herself an adobe home. She would live there for most of the rest of her life. It took her four years to begin, again, to paint. Maybe she left because her profile as an artist was increasing, and she was uncomfortable with fame. Maybe it was due to the mental health issues – the schizophrenia that remained for the rest of her life. Maybe it was because the studio where she lived and worked was going to be demolished. Maybe she just grew tired of the city and longed for a landscape like the one she’d come from, the one to which she would eventually return: wide open land, a horizon stretching full against the sky, a life ordered not by the grid of the city but by the horizontal line where earth meets air.

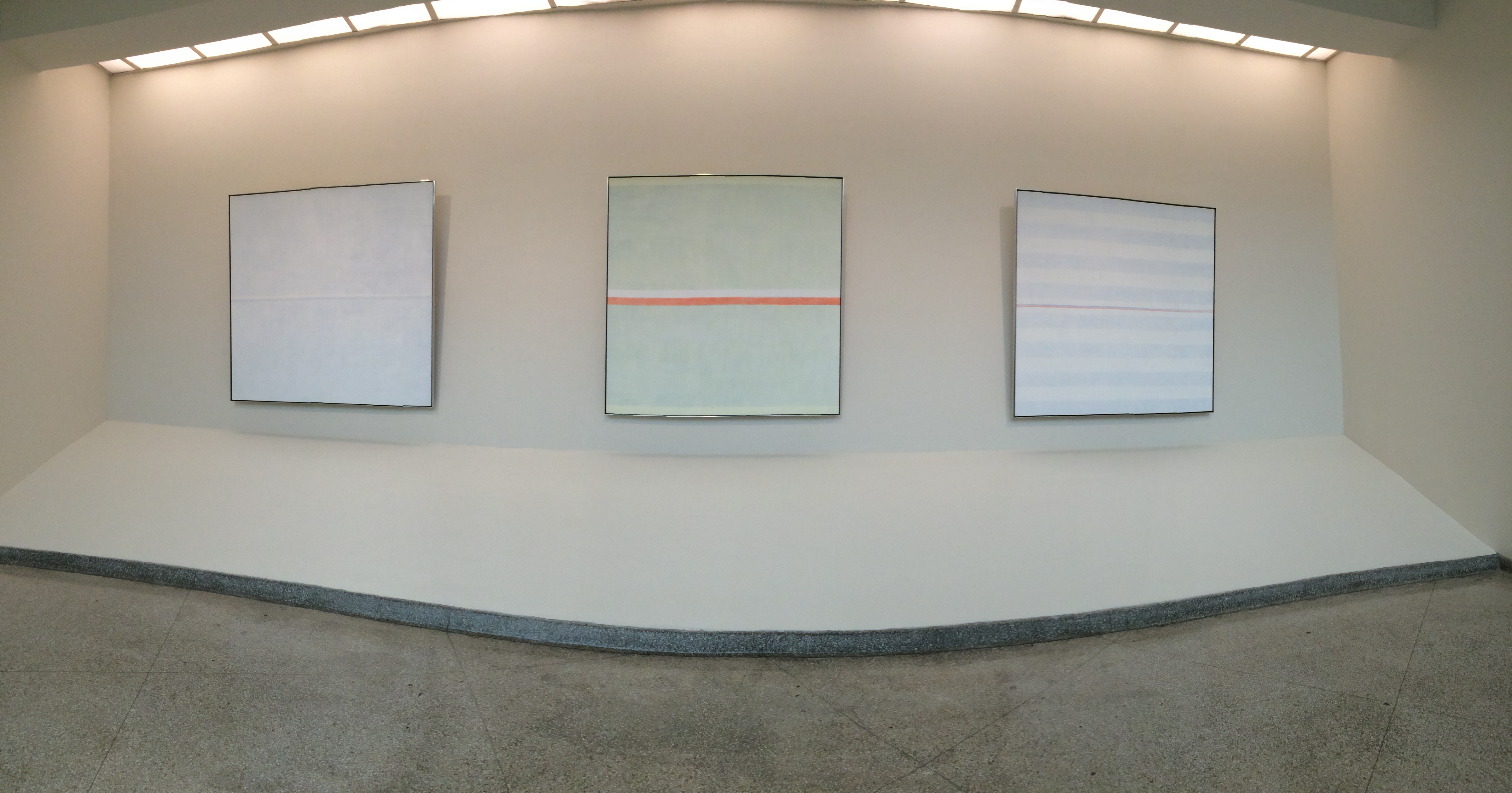

Loving Love (1999); Gratitude (2001); Blessings (2000) by Agnes Martin.

I first met Martin in 2014, when I left New York. I had run away from New York myself – albeit temporarily – and was at a queer writing retreat in LA. Tim Carrier, a writer in my workshop, wrote an essay on Martin, weaving together her work and life story with the week we had shared together in the desert near the sea.

Martin’s work is characterized by a muted color palette and the use of repeating elements – grids and horizontal or vertical lines that cut across the entire canvas. Her canvases are often large and square. She describes herself not as a minimalist, though, but as an abstract expressionist. Tim, in LA, described a painting of hers featuring repeated horizontal lines, the color barely changing from one section of the canvas to the next, and wrote about each bar representing a line on the horizon on which we sat, drank, and wrote together.

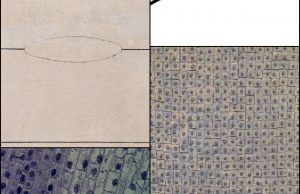

Agnes Martin’s early “biomorphic” paintings.

Martin’s retrospective at The Guggenheim is the first time I’ve seen more than a half dozen of her paintings together. The Guggenheim’s galleries are a stunning site for a retrospective or a show by a single artist. Some of my favorite exhibitions during my decade in New York have been in this space, including the spectacular Cai Guo-Qiang, and the Vasily Kandinsky and Carrie Mae Weems retrospectives. Like Kandinsky, Martin’s work was exhibited (mostly) chronologically beginning on the ground floor with her early paintings. Starting at the ground floor, there’s only one way to experience the work, moving only forward. As we walked in circles upward, we traced the evolution of her work. Because the center of the rotunda is empty, we looked across the space to see horizontal lines against the walls with her previous work below and the work yet to come above. As we walked toward the top floor, it was easy to forget how far we’d come, high up in the galleries now with only a short wall holding us from the edge. Time becomes physical in this space: Time passes as we climb, and Martin’s late work, made near her death, feels near some precipice, only a few steps from a dangerous fall.

Agnes Martin at the Guggenheim

Martin claimed that she was trying to communicate the emotion she felt as she painted, usually something simple and beautiful. Friendship. Calmness. That feeling you get when you wake up from a full night’s sleep, she says. Well rested. Just happy, but without a reason. She would sit for hours and wait for her mind to empty and inspiration to strike. That’s when she would paint. That’s what her paintings should feel like.

And they do. The last time I saw her work, I cried. I went to the Whitney to see the Jeff Koons retrospective. Hungover and in-and-out of a dying relationship, I left my ex-boyfriends house and biked to the museum. Koons’ work was an aesthetically pleasing but soulless celebration of consumption. I loved his color palatte – so bright – and his use of mirrored surfaces that make his audience a part of the work, but I was overwhelmed with a feeling that I can only describe as ickiness by the way his work was made to jar but superficially so. When I finished walking through his retrospective, ending at a giant mound of playdough, I decided to check out the top floor of the museum, the only space dedicated to its permanent collection and not to Koons’ work. Coming up the stairs and leaving the crowd behind, I immediately saw works by pop-influened artists, like Koons: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. These works used color schemes and repetitive elements similar to Koons, but they meant something. These artists painted as though there were stakes. Things, including art, mattered to them.

The Islands (1979)

And then I came around the corner into an empty, brightly lit room. I came around the corner to Agnes Martin. Five or six canvases, The Islands, were hanging on the walls of this room, facing each other, facing me. White canvases cut horizontally with fine lines across. But no – stand a bit closer – these were not white canvases, but ones that bled light blue to light yellow to eggshell to light pink to, finally, yes, white. They look my breath away. I stepped closer. Pencil lines – barely visible from more than a foot away – cut each color from the next. I sat down, facing two of Agnes Martin’s Islands, a beach at my feet, blazing horizons beat by a hot sun in my eyes, and I cried. I cried for my love and I cried for the loss of it and I cried for my hangover and I cried for the beauty that exists if we just sometimes pause to see it and I cried for the world I had just risen out of – Jeff Koons’ world – a world where all that mattered was feeling good, but in the way that candy makes you feel good until you’ve eaten too much of it and begin to feel ill. I felt ill. I sat staring out over Agnes Martin’s Islands. I sat alone in that room bright with stillness, and I cried.

Upper panels: Untitled (1959) and a schematic of a replication fork; Lower panels: Blue Flower (1962) and an image of an onion skin.

So, at The Guggenheim last week, I felt like I was meeting an old friend. On the ground floor, we see Martin’s early work, before she developed her language of grids and lines that she would use for the remainder of her career. Critics call the shapes she used on her early canvases “biomorphic” – they evoke living organisms but aren’t quite anything you could point to. But – as a scientist– I was astonished at the biology in some of her later work. One small painting is a perfect representation of a replication fork, the machinery that copies DNA and that I study, now, in my lab. Another looks like an onion skin under a microscope.

Agnes Martin was born on the flat western plains of Saskatchewan. Her father died when she was young; her mother held her working class family together. She grew up in Vancover, Canada and spent time in college in Bellingham, Washington, forty minutes from where I grew up, and Columbia University, forty minutes from where I live now.

The Sea.

She didn’t start painting until her thirties and didn’t show in a gallery in New York until her forties.

Her work is deeply organic, influenced by the feeling of the world around her. It was standing near a tree, she said, that gave her the first image of a grid on a canvas. Many of her paintings, throughout her career, are untitled. But others are named – for the sea, a tree, a white flower, the horizon – and aren’t meant to reference the object itself, but the feeling of the object. Biting into a ripe piece of fruit. The calm, repetitive motion of ocean waves.

At the Guggenheim, where over 100 of her canvases are on display one after another, her visual vocabulary becomes clear. The horizontal lines and grids, in particular, wash over you canvas after canvas. The individual paintings themselves become repetitions of repetitions, like breaths, like a heartbeat, like a mantra, like waves within the tides, grids within a grid, horizontal lines within this museum, itself cut horizontally by the ascending galleries.

Friendship.

And then a canvas breaks this easy rhythm and takes the breath away. In the middle of Martin’s typical whites and grays is a large canvas covered in shining, metallic gold. Unmistakably Martin, there is a grid cut into the surface. The canvas glows in the studio lighting. Nearly everyone stopped to stare at this piece. Nearly everyone snapped a photo or a selfie with their phone. When I saw the canvas, I gasped – it was so unexpected. And then I read its name: Friendship. Yes. Yes: that rare shining gold in a world of whites and grays, that uneven surface, isn’t that just what a friendship feels like?

I’m particularly drawn to Martin’s large canvases – like The Islands, all twelve of which are on display at the Guggenheim, like Friendship, like her late Untitled pieces. These big canvases take over your entire world. When you stand close to them, they’re all you can see. I can stare at them, be in them, for hours, a meditation, just letting the feeling of them – their color, the single line – wash over me. The ones I respond to most make my skin tingle for as long as I’m willing or able to sit still and look.

Untitled. Photo by Gregory Haney.

The Guggenheim is crowded and busy, but I stumbled onto just enough well-placed benches that offered the invitation to sit and stay a while. For moments, the crowd would quiet, and the shapes of the gallery and the painting would be the only thing I could see, my mind almost empty of the worries of the world. Martin would only paint with an empty mind, her back to the world. This is the gift of her work: a moment, if only a brief one, of opting out, of sitting in peace. I realized that this escape, this calmness so rare in our oversaturated world, is precisely what made me breakdown at The Whitney when I saw her work unexpectedly. A pause, a moment of beauty and peace, is an incredible gift.

We could all – in the world of police brutality, of Donald Trump’s racist, sexist nationalism – use a moment, a brief moment, with our back turned to the world. It’s a moment of privilege, yes. Particularly here, in New York, in Manhattan, at a museum that charges twenty-five dollars a visit. But in our world so saturated with violence and death, it’s imperative to find nature, to find joy. According to Martin, “These paintings are about freedom from the cares of this world.” She certainly understood the difficulties of the world – she was a woman in the male dominated art scene; she was working class; she was gay. My friend Kleaver Cruz started The Black Joy Project, an online space meant to be this type of pause and reprieve. The Guggenheim is pay-what-you-wish on Saturday after 5:45 PM; access to art, to therapy, to beauty, to calm, shouldn’t be accessible only to those who can afford the entry fee.

After visiting the retrospective, my boyfriend and I argued about what made her work special. We were both so moved, but for different reasons. He appreciated the painstaking labor of her work, the focus and precision required to make those lines, to make that grid. He appreciated the care each canvas was shown. I love Agnes for the emotion – for how her work makes me feel. For the peace, the calm. The joy. That’s what she said she wanted her audience to feel. But then, my boyfriend is right, too. No one ever said feeling was easy. Martin would be the first to admit that it is not. Painting with an empty mind took her hours. It required focus. She left the New York and spent most of her life alone.

There is joy in our world. For all the pain and violence, there is beauty. A peach, a tree, the earth and the sky. Things we take for granted, that are always there but not always noticed: dirt, clouds, the horizon. Poet Sharon Olds recently published a book of Odes that celebrate these overlooked things in the world and in our bodies. Martin’s paintings feel so much like visual Odes to me, celebrations of plain things that bring happiness. Olds never quite turns away from violence: more than one of her Odes are letter of thanks for the luck of having never been raped. Still, in her “Ode to Dirt,” toward the end of her book, she writes:

Buds (1959). Photo by Gregory Haney.

“Dear dirt, I am sorry I slighted you, / I thought you were only the background / for the leading characters – the plants / and animals and human animals. / It’s as if I had loved only the stars / and not the sky which gave them space / in which to shine.” It’s dirt, she writes, “who at the end will take us in / and rotate with us, and wobble, and orbit.”

Olds and Martin both pause to notice the negative space in life. Olds and Martin both implore us, in the midst of the world that may try to kill us in big ways and small, to pause, to sit, to find peace or joy, to appreciate beauty even in the dirt, in the sky, in the horizon, in friendship, in gratitude, to breathe, to love, to empty our minds of everything, including worry. Before we left the Guggenheim, I asked my boyfriend to sit with me here, on this bench. Let’s look at the sky for a moment, holding hands. A simple, ordinary thing for two bodies to do. And then let’s get back to the hard work of making our world better.

Agnes Martin is open now through January 11th at The Guggenheim Museum. The museum is free Saturdays after 5:45 PM.

_______________

Photo by Ted Ely.

Joseph Osmundson is a writer and scientist based from rural Washington State. He is an Associate Editor at The Feminist Wire. His writing is collected at www.josephosmundson.com.

0 comments