Black Feminism Will Save My Life

By Eric Anthony Grollman

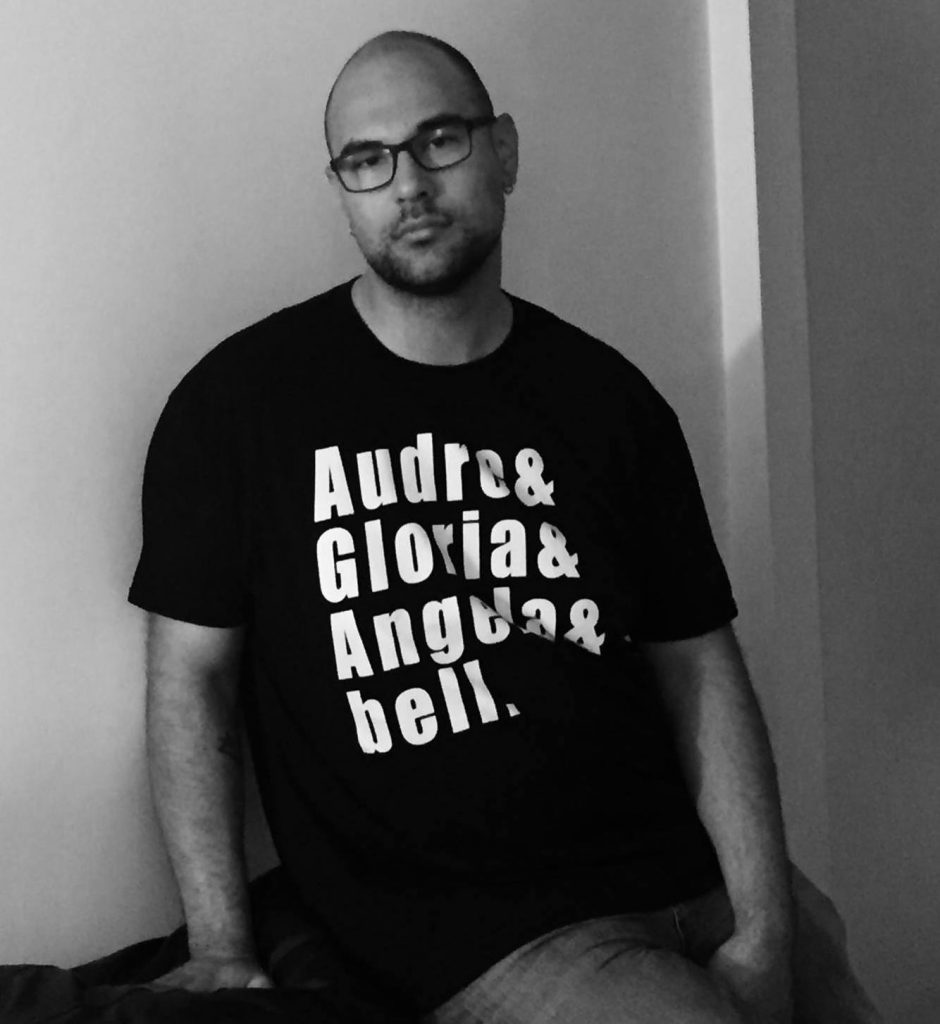

Like most Black folks, I have a Black woman to thank for my existence (my mother) who, in turn, has another Black woman to thank for her existence (my grandmother), and so on. I have them, and my aunts and older cousins to thank for my survival in this oftentimes-hostile world. Black women babysitters, neighbors, friends, teachers, mentors, and colleagues have educated me, protected me, supported me, advised me, and loved me in childhood, adolescence, and now adulthood. Now, as I fumble through my academic career, simultaneously trying to recover from the trauma of grad school, survive the tenure-track, and thrive as a scholar-activist, I have Black women researchers, theorists, and writers to lean on during my journey. Indeed, Black feminism will save my life.

Like most Black folks, I have a Black woman to thank for my existence (my mother) who, in turn, has another Black woman to thank for her existence (my grandmother), and so on. I have them, and my aunts and older cousins to thank for my survival in this oftentimes-hostile world. Black women babysitters, neighbors, friends, teachers, mentors, and colleagues have educated me, protected me, supported me, advised me, and loved me in childhood, adolescence, and now adulthood. Now, as I fumble through my academic career, simultaneously trying to recover from the trauma of grad school, survive the tenure-track, and thrive as a scholar-activist, I have Black women researchers, theorists, and writers to lean on during my journey. Indeed, Black feminism will save my life.

The Gifts of Black Feminism

I was introduced to the framework of intersectionality and Black feminist theory more generally, as an undergraduate student at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC). In one assignment from my upper-level Women and the Media course, taught by Elizabeth Salisbury (a white anti-racist feminist instructor), I reflected on my intersecting sex, gender, sexual, and racial identities. I still remember being blown away by all that I learned in my Women’s History and Black Women’s History courses, taught by Dr. Michelle Scott (a Black woman history professor); I was shocked by how little I knew about Black women’s involvement in the abolition, suffrage, feminist, Civil Rights, and Black Power movements. Although Black feminism was not treated as a central theoretical framework in most of my graduate school courses, it has remained a focal point in my own research, teaching, and service.

Graduate school – MA and PhD in sociology from Indiana University – is where I first discovered the toxic, soul-crushing nature of academe. This training was not a period of self-discovery and consciousness-raising; if anything, grad school was set to “beat the activist” out of me, to de-radicalize me as a scholar-activist and to sever my ties with my communities. With only one Black woman professor on faculty and very little support of critical intersectional work, my graduate department was not a place that was a welcome home for Black feminists and womanists. These years were soul-crushing – even traumatizing; now three years later, I am seeing a trauma-certified therapist and taking Lexapro for the ongoing generalized anxiety disorder. I was knocked out of my metaphorical Black feminism life raft and nearly drowned as a result.

The Gift of Self-Definition

Late in my last year of graduate school, and subsequently in my tenure-track position at the University of Richmond, I rediscovered the life-giving force of Black feminism. In a blog post, I wrote about Dr. Patricia Hill Collins’s 2012 book, On Intellectual Activism; I devoured every word of her book as it named the kind of work I aspired to do (intellectual activism) and made such work seem like a natural extension of the career of Black feminist scholars. Her book reintroduced me to the core components of Black feminist theory, which she articulated in her book, Black Feminist Thought – in particular, the intersections among systems of oppression and the importance of self-definition for Black women. I took up her notion of self-definition in declaring that I am pursuing my career in sociology on my own terms – inherently activist, or nothing at all.

Late in my last year of graduate school, and subsequently in my tenure-track position at the University of Richmond, I rediscovered the life-giving force of Black feminism. In a blog post, I wrote about Dr. Patricia Hill Collins’s 2012 book, On Intellectual Activism; I devoured every word of her book as it named the kind of work I aspired to do (intellectual activism) and made such work seem like a natural extension of the career of Black feminist scholars. Her book reintroduced me to the core components of Black feminist theory, which she articulated in her book, Black Feminist Thought – in particular, the intersections among systems of oppression and the importance of self-definition for Black women. I took up her notion of self-definition in declaring that I am pursuing my career in sociology on my own terms – inherently activist, or nothing at all.

Unfortunately, self-definition has not been a smooth process. I regularly burn the candle at both ends trying to exceed the expectations of mainstream academe (to keep my job) and subverting the academic status quo. At any given moment, I waver between fear of my grad school advisors’ warning that I will be irrelevant (to mainstream sociology) and smugness as I intentionally buck the system. It is an unfair burden to have to weigh between keeping my job and liberating my communities.

The Gift of Liberation from Oppressive Institutions

But, Black feminism has somewhat eased this ambivalence. The good Lorde – Audre Lorde – once wrote, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Though telling myself that I am simply working within the system to enact change has helped me to sleep at night, I realize that playing by the rules of the Ivory Tower serves to perpetuate the status quo in academe and society more generally. How can I expect to challenge academic injustice by reinforcing unjust practices? Lorde once said that “your silence will not protect you” – a powerful phrase prominently displayed on a bumper sticker on the very laptop I am using now to write this essay. Lorde has shattered any naïve notion that playing it “safe” in academe will ever ensure my safety, livelihood, and status. To be a good little mainstream sociologist is to be complicit in the discipline’s racism.

Yet, contemporary Black feminists have been incredible role models for avoiding the seduction of letting the academy validate my existence. Oh, and have I been seduced, even to the point of internalizing the view that I am only valuable as a member of society so long as I publish and that leisure and relaxation are tools of the devil. I am thankful that a friend, Dr. Abigail A. Sewell, introduced me to The Black Academic’s Guide to Winning Tenure – Without Losing Your Soul as we were finishing up our respective dissertations. A couple of years later, I found myself having a phone conversation with the book’s lead author, Dr. Kerry Ann Rockquemore, to ask for advice about moving my blog, ConditionallyAcepted.com, to InsideHigherEd.com, which also features her biweekly academic advice column, “Dear Kerry Ann.” Through a series of conversations with her, as well as various resources produced by her organization (National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity),I have been inspired to let my big dreams and goals guide me, rather than being driven (or coerced) by external validation like tenure and promotion.

Yet, contemporary Black feminists have been incredible role models for avoiding the seduction of letting the academy validate my existence. Oh, and have I been seduced, even to the point of internalizing the view that I am only valuable as a member of society so long as I publish and that leisure and relaxation are tools of the devil. I am thankful that a friend, Dr. Abigail A. Sewell, introduced me to The Black Academic’s Guide to Winning Tenure – Without Losing Your Soul as we were finishing up our respective dissertations. A couple of years later, I found myself having a phone conversation with the book’s lead author, Dr. Kerry Ann Rockquemore, to ask for advice about moving my blog, ConditionallyAcepted.com, to InsideHigherEd.com, which also features her biweekly academic advice column, “Dear Kerry Ann.” Through a series of conversations with her, as well as various resources produced by her organization (National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity),I have been inspired to let my big dreams and goals guide me, rather than being driven (or coerced) by external validation like tenure and promotion.

Similarly, I was inspired by Dr. Zandria F. Robinson who, when under a national conservative media attack on her online writing (and character, politics, appearance, and menstrual cycle), had the last laugh as she maintained her value and integrity no matter the institution that employed her. Academic institutions, as with any social institution, were overwhelmingly built by and for wealthy white cishet men without disabilities, and they continue to systematically exclude and exploit everyone else. I will never be free if I live my life defined by institutions that hate me and people like me. Perhaps because of the simultaneity of and intersections among racism, sexism, and classism, many Black women have never been under the illusion that an institution will value, liberate, and uplift them; instead, some have taken to carving out safe spaces in these hostile institutions or creating their own institutions and organizations outside of them.

The Gift of Positionality

Black feminists’ emphasis on positionality – that is, recognizing how one’s intersectional social position shapes one’s view of the world – has allowed me to embrace the influence of my personal biography on my scholarship. Through my graduate training, I was taught that legitimate sociological scholarship focuses on social institutions (e.g., medicine), not social groups – especially not marginalized groups. I was encouraged to embrace a professional identity as a medical sociologist who just happens to study Black and Latinx people, LGBTQ people, and women; I was discouraged from being a sociologist of sexualities, of gender, or of race. The greatest suspicion of all was of sociologists who were not simply experts on some group, but were a member of the group: Black sociologists, queer sociologists, feminist sociologists, disabled sociologists, fat sociologists. Having expertise “of” some sociological topic creates enough distance between the presumably objective sociologist and her research. But, to be your topic threatens the appearance of objectivity.

It has taken me a few years to actually embrace my positionality in my scholarship. Yes, I am Black, and queer, and non-binary, and fat, and a feminist. And, my work as an activist – to advance these causes and liberate these communities – is the primary motivation behind my research on sexualities, gender, race and ethnicity, and weight. I have Black feminists to thank for taking objectivity to task and for celebrating positionality rather than pretending to be objective. My work has become easier now that I allow myself to say I am a Black queer sociologist (who happens to study health), rather than forcing the label “medical sociologist” (who happens to study race, ethnicity, gender, and sexualities).

The Gift of Self-Care as a Political Act

Black feminist writing about self-care will save my life. This self care is different from the neoliberal “life hack” and yoga-and-mindfulness-fad stuff that fills my Facebook feed. As Lorde argued, self-care is a political act; the audacity of self-preservation within institutions and a national context that is set on eliminating Black women is a far cry from white middle-class folks’ efforts to make their privileged lives just a little bit calmer. When racial organizations slant toward the plight of Black cishet men, when feminist organizations champion the causes of middle-class white cishet women, when the rest of the country doesn’t give a damn either way – Black women are left on their own to simply survive from day to day. Self-care as a counter to others’ efforts to eliminate you is nothing short of an act of warfare.

Black feminism’s emphasis on self-care has forced me to rethink how own efforts to survive and thrive – how I approach and conceptualize them. It convinced me to critically analyze the features of graduate school and the academy more generally that left me with a PhD, generalized anxiety disorder, and complex trauma at the end of my graduate training. Had I been aware of the oppressive structure and culture of mainstream academe from the start – the pervasive micro-aggressions, the devaluing of scholarship on my own communities, the elitist emphasis on Research I careers, and the efforts to “beat the activist” out of me – I may have been better prepared with ways to preserve myself. Hindsight is 20-20; now, I am better armed as I take on the rough road of the tenure-track. I have sought out mental health care, I have looked for supportive critical communities, I have taken on new ways to embrace authenticity in my scholarship, and so forth. Thanks to Black feminists, I am aware that my survival falls in my hands alone; I could find myself dead or near-death on the other side of tenure if I continue to naively assume my department and university cares about my well-being beyond my CV.

The Gift of Entrepreneurship

Beyond simply surviving, I am grateful to Black feminist friends and colleagues who have modeled for me bravery in the face of vulnerability, invisibility, exploitation, and extinction. Since starting Conditionally Accepted, I have become connected with a wide network of smart, critical, and creative people. And, I have noticed an interesting pattern: most of the scholars who are successful public intellectuals and academic entrepreneurs are Black women. Dr. Manya Whitaker started her own educational consulting business, Blueprint Educational Strategies. Dr. Fatimah Williams Castro runs her own business to help academics develop alternative careers (“alt-ac”) – Beyond the Tenure Track. Dr. Michelle Boyd started and runs Inkwell Academic Writing Retreats. Dr. Chavella Pittman runs workshops on bias and incivility in the classroom through her business, Effective & Efficient Faculty. Dr. Crystal Marie Fleming is just beginning to offer professional development workshops. And, of course, there is the Oprah of professional development, Dr. Kerry Ann Rockquemore, founder and CEO of NCFDD.

Giving Back

I would be remiss to devote this essay solely to the gifts I have received from Black feminist scholarship and activism. To me, Black feminism is not simply an ideology and movement from which others (including me) passively benefit. To be a Black feminist is to be committed to advancing intersectionality, positionality, and self-definition and to liberating all Black women. And, to be an ally to Black feminists, I feel a sense of obligation to use my generally privileged status as an individual often perceived as a cisgender man to live into this commitment.

I am still figuring out what that means for the long-haul and on a day-to-day basis. At the baseline, I regularly draw upon a principle of the Virginia Anti-Violence Project (for which I sometimes volunteer) to ask, “How does this decision/action/policy humanize, liberate, and intentionally include people and communities of color?” – tailored to ask specifically about Black women.

How does this decision/action/policy humanize, liberate, and intentionally include Black girls, women, and femmes?

Failing to regularly prioritize the inclusion, support, and advancement of Black women means that white cishet masculinity pervades as a norm, as the default; attention to Black women comes up only when they demand it or when the dominant group bothers to attend to diversity (which usually fails to consider intersectionality). When I plan events on campus, I aim to center the voices of women of color, especially when the topic at hand disproportionately affects them and/or affects them in unique ways. For example, I have begun organizing workshops at academic conferences on supporting intellectual activists and protecting them from professional harm and public backlash; since women of color have been the most vulnerable to these attacks, I have centered their experiences. When Black women panelists are available, I center their voices; when they are not, I cite their work and refer to their writing for further information.

Perhaps my biggest commitment to Black feminism to date, at least as a scholar, is the co-editing of an anthology that will celebrate academic bravery among women of color scholars. With my colleague and friend, Dr. Manya Whitaker, I am currently collecting narratives and creative works from women of color academics that reflect upon times that they spoke up, took risks, reconceptualized what it means to be a scholar, advocated for change, overcame adversity, etc. The inspiration from this work came from a comment that Dr. Brittney Cooper casually made as a fellow panelist at the Parren-Mitchell Symposium on Intellectual Activism at the University of Maryland in April 2015. She remarked that there was too much cowardice in academy, and that what we need to best support intellectual activists is more academic bravery. As far as I have seen, no one else is talking about this, despite the widespread culture of fear and risk-aversion in academia. But, from my observations, some of the most innovative, entrepreneurial, creative, and all-around badass scholars today are women of color. I am incredibly moved by their individual and collective bravery and want to document and celebrate it; I want to put it into a single book (for now) so future women of color scholars will already have a manual for being brave, hopefully forgoing years of floundering, fear, isolation, self-doubt.

This is just the beginning. I owe my life to Black women and Black feminism. They gave me life. They have sustained my life. They inspire me. They care for me and love me. Black women rule the world – I’m just doing my part to see that the rest of the world wakes up to that reality!

______________________________________________________

Eric Anthony Grollman is an Assistant Professor at the University of Richmond. Their research examines the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed communities. Dr. Grollman is the editor of Conditionally Accepted – a weekly career advice column for marginalized scholars on Inside Higher Ed.

Eric Anthony Grollman is an Assistant Professor at the University of Richmond. Their research examines the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed communities. Dr. Grollman is the editor of Conditionally Accepted – a weekly career advice column for marginalized scholars on Inside Higher Ed.

2 Comments