Who is Killing Us

By Terrion L. Williamson

On April 1, 1979, 1,500 people gathered in the streets of Boston to memorialize the lives of six black women who had been murdered within a two-mile radius of each other beginning in January of that year. By May the number of victims would rise to twelve. During the memorial march, Mrs. Sara Small, the aunt of the fifth victim, Daryal Ann Hargett, posed a simple question, but one with serious and long-lasting reverberations:

“Who is Killing Us?”

Mrs. Small’s question was critical because in its asking it formulated a theory of the social—a black social—that refused to allow victims to remain individual, that made racialized gender violence a community concern and not just a “woman’s issue,” and that made the lives of black women the focal point of a collective “us” that included black men and boys. But Mrs. Small’s question had even further implications.

Among the marchers that spring day was Barbara Smith, a founding member of the Combahee River Collective, which just two years earlier had published “The Combahee River Collective Statement,” a document that has since become foundational to black feminist thought and women of color organizing. Smith was outraged that most of the speakers at the march were men whose most immediate response to the crisis was to tell black women they needed to remain indoors for their safety and to rally other men to “protect” their women, while never actually addressing the gendered nature of the murders.

Following the march, Smith and other members of the Collective produced and began distributing a pamphlet entitled “Six Black Women: Why Did They Die?” in which they argued the importance of recognizing the role of sexual violence in the deaths of the murdered black women. They made clear that it was not just race and not just gender but race and gender that had made those women especially vulnerable, stating that what had happened in Boston was “a thread in the fabric of violence against women.” For the Collective, “protecting” black women meant that black men needed to collectively check their own physical, emotional, and verbal assaults on black women, particularly since it most often turns out to be black men who are the instigators of violence against black women—even in serial murder cases.

Thus while some community advocates were primarily concerned with linking the murders of the Boston women to larger histories of racial oppression, the Collective intervened to ensure that the women’s murders were recognized as the effect of intersecting oppressions and that advocating on behalf of those women and women like them meant working to end racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, and all other forms of discrimination, simultaneously. It is within this context that Mrs. Small’s question became significantly more than a concern about the identities of individual perpetrators. That is, “who is killing us” bordered on the rhetorical; it was not just a question but the beginnings of a declarative statement that was continued by the work of the Collective and other community advocates who were dedicated to exposing the structural, social and political forces behind the violence against black women.

But let’s be clear, given that the social and economic conditions that lead to violence still exist, the concern over who is killing us, all of us, is as important today as it was in Boston thirty-plus years ago. And while the violence against us continues to take on various forms—the Prison Industrial Complex, healthcare disparities, educational disadvantages, the list goes on—and must undoubtedly continue to be challenged, the deaths and disappearances of black women and children that continue to occur at (what should be) alarming rates must also become more of a priority in our struggles for social justice. According to the National Crime Information Center, hundreds of thousands of black people, most but not all of them women and children, are reported missing each year. And, the serial murders of black women continue on unabated. In just the past ten years black women have been the targets of serial killers in at least seven U.S. cities, including Detroit, Los Angeles, Cleveland, OH, Jacksonville, FL, Rocky Mount, NC, and Peoria, IL.

Although vitally important, this is not simply a matter of figuring out the identities of those individuals who prey on the vulnerable. Rather, the concern over who is killing us must be, first and foremost, about dismantling the conditions that make us vulnerable in the first place. And we know that part of that “conditioning” has to do with the fact that, historically, the lives of black people generally, and black women and children in particular, have been of little consequence to the national public—unless, of course, they are being used for political expediency in debates around welfare, crime, cultural pathology, and the like. This is made evident, at least in part, by what has sometimes been referred to as the “missing white woman syndrome”—the disproportionate coverage of young, attractive, and often middle-class white women who go missing—and the dearth of coverage of missing and mutilated black people in national and local media. But advocacy around those lives is also tragically absent from the agendas of many black political and social organizations.

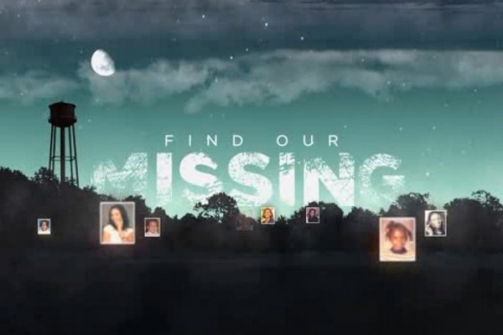

TV One, in partnership with the Black and Missing Foundation, is currently embarking on a project that will begin to act as a corrective to the national media landscape, and even more importantly, will hopefully help spur a national conversation about the value of black lives and how we might go about saving them. On Wednesday, January 18 at 10 PM ET the first of a ten-part series devoted to bringing attention to disappeared black people called Find Our Missing will begin airing. The series, which is hosted by S. Epatha Merkerson of Law & Order and Lackawanna Blues, will be complemented by social media and online content that will provide information on additional missing persons cases and other social justice issues.

Of the twenty people to be featured over the course of the series, nine are women, six are girls between the ages of two and fifteen, three are boys between the ages of three and twelve, and two are men. Tia Smith, one of the executives in charge of production at TV One, says the intention of the show is to represent a full spectrum of black Americans who are declared missing, and that the hope is not just that it will be something of a corrective to the lack of media coverage of disappeared black people, but that it will also serve as a “clarion call for activeness and community involvement.”

Smith also says that the individual cases featured on Find Our Missing, which is produced for TV One by Tower Productions, were selected for their potential to be compelling and to “pull at the heart strings of people.” That is to say, they want to ensure that people watch the show because they feel moved by the stories of the people who are featured. While this logic may make sense for a cable network that is concerned both with remaining economically viable and appealing to the widest possible audience, we must remain mindful that our own sense of justice is not so limited. Ultimately, those of us who are invested in saving our lives can little afford to pick and choose whom we save. For if we are not just as concerned about the prostitute woman who may have become the target of a serial killer as we are the honor student who disappeared while walking home from school, we risk simply reproducing the same conditions we otherwise seek to eliminate.

Whatever the case, TV One has begun the truly laudable task of calling attention to the many black people—boys and girls, women and men—who go missing in this country every year. It is one very important assist in our struggles for full human rights and social justice, and it is an effort that deserves our attention.

I’ll be watching.

_______________________________________

Terrion L. Williamson is Assistant Professor of English and African American and African Studies at Michigan State University and holds a J.D. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her work focuses on narratives of black women in contemporary popular culture, feminicide and gendered violence against women of color, and black religious discourse. She is currently working on a manuscript that examines the role of the black female body and black feminist practice in the making of black sociality.

Terrion L. Williamson is Assistant Professor of English and African American and African Studies at Michigan State University and holds a J.D. from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her work focuses on narratives of black women in contemporary popular culture, feminicide and gendered violence against women of color, and black religious discourse. She is currently working on a manuscript that examines the role of the black female body and black feminist practice in the making of black sociality.

12 Comments