The “Identity Politics” We’re Not Talking About

By William Ruhm

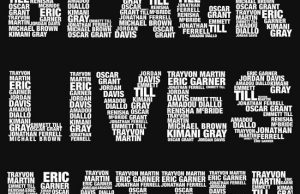

I first encountered the term “identity politics” while organizing with the Black Lives Matter movement through a socialist group in Boston. When one white ally from the group used the term, she explained to me that (in the context of anti-racist organizing) “identity politics” refers to the belief that Black Americans possess a unique and authoritative perspective on issues relating to racial oppression on the basis of having experienced this oppression, while white Americans definitively lack this particular perspective. She proceeded to problematize “identity politics,” understood in this way, on the grounds that Black Americans claiming unique, situated knowledge that white allies lack derails the development of broad anti-racist movements that link activists across race, class, and other identities. In later conversations, other white allies from the group raised further objections to “identity politics,” most notably that its logic implies the existence of a single, homogenous Black American experience and that it re-inscribes strict racial separatism. However, rather than blaming Black Americans for derailing anti-racist organizing by invoking their lived experiences of racial oppression, white allies might consider how we derail organizing by refusing to accept others’ challenges to our perception of the authority of our lived experiences of racial privilege and dominance.

I first encountered the term “identity politics” while organizing with the Black Lives Matter movement through a socialist group in Boston. When one white ally from the group used the term, she explained to me that (in the context of anti-racist organizing) “identity politics” refers to the belief that Black Americans possess a unique and authoritative perspective on issues relating to racial oppression on the basis of having experienced this oppression, while white Americans definitively lack this particular perspective. She proceeded to problematize “identity politics,” understood in this way, on the grounds that Black Americans claiming unique, situated knowledge that white allies lack derails the development of broad anti-racist movements that link activists across race, class, and other identities. In later conversations, other white allies from the group raised further objections to “identity politics,” most notably that its logic implies the existence of a single, homogenous Black American experience and that it re-inscribes strict racial separatism. However, rather than blaming Black Americans for derailing anti-racist organizing by invoking their lived experiences of racial oppression, white allies might consider how we derail organizing by refusing to accept others’ challenges to our perception of the authority of our lived experiences of racial privilege and dominance.

In “Essentialism and Experience,” bell hooks challenges Diana Fuss’s argument that members of marginalized groups invoking this authority on the basis of their lived experiences shuts down conversations. Although Fuss and hooks are explicitly concerned with the context of the college classroom, their arguments prove relevant to that of anti-racist organizing:

According to Fuss, issues of “essence, identity, and experience” erupt in the classroom primarily because of the critical input from marginalized groups. Throughout her chapter, whenever she offers an example of individuals who use essentialist standpoints to dominate discussion, to silence others via their invocation of the “authority of experience,” they are members of groups who historically have been and are oppressed and exploited in this society. Fuss does not address how systems of domination already at work in the academy and the classroom silence the voices of individuals from marginalized groups and give space only when on the basis of experience it is demanded […] The politics of race and gender within white supremacist patriarchy grants them this “authority” without their having to name the desire for it […] At the same time, I am concerned that critiques of identity politics not serve as the new, chic way to silence students from marginalized groups.

Similar to the shortcomings of Fuss’s analysis that hooks illuminates, the logic white allies cite for their opposition to “identity politics” “does not address how systems of domination already at work” within anti-racist organizations “silence the voices of individuals from marginalized groups.” White allies bring a belief in the authority of our white experiences into conversations and organizing meetings with Black Americans. The difference is that we do not, and are not often challenged to, recognize these experiences as deriving from our whiteness – our white racial identities.

Vox contributor Matthew Yglesias arrives at this conclusion in his piece “All Politics is Identity Politics” when he writes, “The truth is that almost all politics is, on some level, about identity. But those with the right identities have the privilege of simply calling it politics while labeling other people’s agendas ‘identity.’” Yglesias’ conclusion rings true alongside hooks’ argument. The privilege of whiteness is that one’s experientially rooted ways of understanding pose as the norm and thereby as objectively valid. Within our dominant discourse, Blackness and other marginalized identities are identified as tendentious and thereby subject to challenge on grounds of the perceived objectivity of the dominant identity.

All of this being “said,” the aforementioned criticism that “identity politics” will fragment organizing and impede the development of formidable social movements deserves consideration. To reframe this criticism as a question: Is it possible for anti-racist organizers to challenge normative whiteness without risking the fragmentation of various movements? Many activists seem to believe we cannot, and as a result err towards avoiding challenges to the implicitly-sanctioned dominance of white perspectives. At one point last year, the socialist group I was a part of took on a leading role in organizing against police brutality in Boston through involvement in a 150 person coalition of activists. During the socialist group’s internal meetings, white allies expressed increasing frustration with activists of color who were pushing to set aside time for discussions on the unwillingness of white allies to listen more and speak less in order to create adequate space for Black voices. Members of the socialist group argued that such conversations on internal dynamics would only divert the coalition’s energies from what they believed to be the more important objective: winning victories against police brutality.

All of this being “said,” the aforementioned criticism that “identity politics” will fragment organizing and impede the development of formidable social movements deserves consideration. To reframe this criticism as a question: Is it possible for anti-racist organizers to challenge normative whiteness without risking the fragmentation of various movements? Many activists seem to believe we cannot, and as a result err towards avoiding challenges to the implicitly-sanctioned dominance of white perspectives. At one point last year, the socialist group I was a part of took on a leading role in organizing against police brutality in Boston through involvement in a 150 person coalition of activists. During the socialist group’s internal meetings, white allies expressed increasing frustration with activists of color who were pushing to set aside time for discussions on the unwillingness of white allies to listen more and speak less in order to create adequate space for Black voices. Members of the socialist group argued that such conversations on internal dynamics would only divert the coalition’s energies from what they believed to be the more important objective: winning victories against police brutality.

Ultimately, consensus within the 150 person coalition did not allow such conversations on internal dynamics to occur in a meaningful way. As a result, many People of Color left the coalition, citing as their reason for leaving frustration with white allies’ refusal to create adequate space for their voices. White allies from within the socialist group repeatedly named “identity politics” as the factor to blame for the gradual disintegration of the coalition. They claimed that the Black activists who left were too concerned with fighting privilege and microaggressions and not concerned enough with fighting for systematic change. This assessment misses the mark. What actually derailed the group was the failure of white allies to do the work of listening and reassessing our opinions when Black organizers challenged our perspectives. It was not Black organizers’ unwillingness to set aside their identities and experientially-rooted perspectives that prevented group cohesion. It was white allies unwillingness to set aside our own.

Besides failing to account for the fact that white as well as Black Americans speak from a place of racial identity, the term “identity politics” misses the point that Black Americans speaking from their experience living under racial oppression is extremely valuable to anti-racist organizing work. There is something fundamentally formative in the lived experiences of racial oppression, that gives Black Americans a unique perspective upon how we as anti-racists must organize, a perspective that therefore makes them more qualified to speak, and to speak the most, in anti-racist organizing efforts. What is it that Black Americans understand about racism that white Americans like myself are definitively not capable of grasping? hooks explains:

I know that experience can be a way to know and can inform how we know what we know […] It cannot be acquired through books or even distanced observation and study of a particular reality. To me this privileged standpoint does not emerge from the “authority of experience” but rather from the passion of experience, the passion of remembrance […] When I use the phrase “passion of experience,” it encompasses many feelings but particularly suffering, for there is a particular knowledge that comes from suffering. It is a way of knowing that is often expressed through the body, what it knows, what has been deeply inscribed on it through experience. This complexity of experience can rarely be voiced and named from a distance. It is a privileged location, even as it is not the only or even always the most important location from which one can know.

No matter how many statistics we can string together or how many Black activists from our nation’s history we can recall, White activists lack the ”particular knowledge that comes from suffering” that hooks refers to as ”passion of experience.” This form of knowledge cuts deep. It permeates the body. It is not reducible to any level of academic understanding of the realities of racism, but instead comes from the physical and emotional weight of living every minute of one’s life in a country built from top to bottom upon the premise of your negation, exploitation, and destruction. That Black Americans speak from this place of deeper, experientially-rooted knowledge on matters of anti-Black racism does not imply, as critics of “identity politics” argue, that Black American identities are homogenous. The nature and the extent of this form of knowledge is surely contingent upon Black Americans’ different, respective experiences and intersectional identities. Yet it is a form of knowledge that is definitively Black. Yglesias puts it best: All politics is identity politics.

Decrying Black Americans who invoke their experiences as uniquely relevant to anti-racist work not only denies this fact; it implicitly re-inscribes whiteness as dominant and powerful over Blackness. Therefore, I call on white allies to consider how we derail organizing by refusing to accept the challenges of others and to challenge our perception of our racial privilege and lived experiences. I find that this is a better alternative to blaming Black Americans for invoking their lived experiences of racial oppression as the derailment of anti-racist organizing.

Decrying Black Americans who invoke their experiences as uniquely relevant to anti-racist work not only denies this fact; it implicitly re-inscribes whiteness as dominant and powerful over Blackness. Therefore, I call on white allies to consider how we derail organizing by refusing to accept the challenges of others and to challenge our perception of our racial privilege and lived experiences. I find that this is a better alternative to blaming Black Americans for invoking their lived experiences of racial oppression as the derailment of anti-racist organizing.

William is a Boston-based activist, writer, and aspiring clinical social worker. He has organized as a part the Black Lives Matter Movement and the BDS movement to end the Israeli occupation of Palestine. William’s academic interests include Labor History and the History of Blackface Minstrelsy in the United States. In his free time, William can be found biking around Southwest Boston or reading a book in a coffee shop.

William is a Boston-based activist, writer, and aspiring clinical social worker. He has organized as a part the Black Lives Matter Movement and the BDS movement to end the Israeli occupation of Palestine. William’s academic interests include Labor History and the History of Blackface Minstrelsy in the United States. In his free time, William can be found biking around Southwest Boston or reading a book in a coffee shop.

0 comments