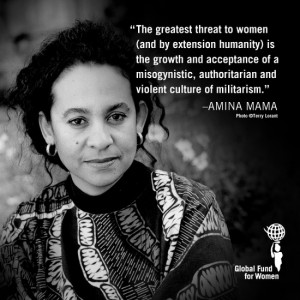

Feminists We Love: Professor Amina Mama

Professor Amina Mama is Nigerian-British feminist intellectual who has worked for over two decades in research, teaching, organizational change and organizing, and editing in Nigeria, Britain, The Netherlands, South Africa and the USA. She spent a decade at the University of Cape Town’s African Gender Institute where she led the collaborative development of feminist studies and research for African contexts. Author and editor of a range of books and articles on state feminism, militarism, colonialism, feminist methodologies grounded in African contexts, Amina currently earns her living as a professor of Women and Gender Studies at the University of California. She pursues longstanding interests in radical knowledge production and dissemination through research and teaching, as founding editor of the open access gender studies journal Feminist Africa, and most recently by working in collaboration with Director/Producer Yaba Badoe on the production of two documentary films: the Witches of Gambaga (2011) and The Art of Ama Ata Aidoo (2014).

Professor Amina Mama is Nigerian-British feminist intellectual who has worked for over two decades in research, teaching, organizational change and organizing, and editing in Nigeria, Britain, The Netherlands, South Africa and the USA. She spent a decade at the University of Cape Town’s African Gender Institute where she led the collaborative development of feminist studies and research for African contexts. Author and editor of a range of books and articles on state feminism, militarism, colonialism, feminist methodologies grounded in African contexts, Amina currently earns her living as a professor of Women and Gender Studies at the University of California. She pursues longstanding interests in radical knowledge production and dissemination through research and teaching, as founding editor of the open access gender studies journal Feminist Africa, and most recently by working in collaboration with Director/Producer Yaba Badoe on the production of two documentary films: the Witches of Gambaga (2011) and The Art of Ama Ata Aidoo (2014).

I first met Professor Amina Mama at the African Feminist Forum in Uganda in 2008. I had read her early book Beyond the Masks: Race, Gender and Subjectivity as well as several of her publications on African feminist thought and practice. In Uganda she spoke about the paradox of Africa’s decreasing civil wars and increasing militarism in the context of globalized neoliberal oppression and imperialism. What struck me about Professor Mama’s approach was her insistence on sabotaging the false separation between African feminist thought and activism. Over the last months, I have had the pleasure of working with her on two upcoming editions of the journal Feminist Africa, dedicated to the theme ‘feminism and pan-Africanism’. The editions pose the question: what can a genuinely radical pan-African engagement contribute to the transformation of multiple systemic oppressions, including gendered oppressions, that continue to sustain the under-development of the resource-rich African continent?

I first met Professor Amina Mama at the African Feminist Forum in Uganda in 2008. I had read her early book Beyond the Masks: Race, Gender and Subjectivity as well as several of her publications on African feminist thought and practice. In Uganda she spoke about the paradox of Africa’s decreasing civil wars and increasing militarism in the context of globalized neoliberal oppression and imperialism. What struck me about Professor Mama’s approach was her insistence on sabotaging the false separation between African feminist thought and activism. Over the last months, I have had the pleasure of working with her on two upcoming editions of the journal Feminist Africa, dedicated to the theme ‘feminism and pan-Africanism’. The editions pose the question: what can a genuinely radical pan-African engagement contribute to the transformation of multiple systemic oppressions, including gendered oppressions, that continue to sustain the under-development of the resource-rich African continent?

****

HA: What does African feminism mean to you?

Amina: Feminism is the theory, philosophy, politics and practices of the movement for women’s liberation. It has numerous manifestations all over the world. It offers us tools and strategies for demystifying and working to change the myriad historical and material realities that oppress and exploit women. I prefer to refer to “feminism in Africa” or “African feminisms” rather than to use the singular term “African feminism” because the theories and practices that comprise the struggle for women’s liberation vary widely according to context. Feminist movements – in Africa as elsewhere – arise out of the rich array of political and ideological histories, cultures, languages, creeds, and classes. As an African person, I am personally invested in the multiplicity of feminisms that emerge out of the diverse historical specificities that comprise African realities, and the numerous configurations of power, knowledge and action that shape life on the continent. Because there are so many nations and nationalities on the African continent, feminism in Africa is inherently transnational. The continent has seen many civilizations, and long histories of trade and exchange with the rest of the world, including the recent stories of imperialism and colonialism, feminism takes multiple forms, rooted in struggles that predate and can therefore transcend the structures of modern states, to address the patriarchal legacies of capitalism at multiple locations.

As an intellectual worker and thinker, I am particularly interested in the application of feminism to the analysis and demystification of women’s oppression and the manner in which this is always inflected by the interactions of gender and sexuality with other dimensions of systemic injustice such as nationalism, ethnocentrism, stratifications of class, caste, location and social status, heteronormativity, unjust and undemocratic political and economic regimes. All of these affect our psychology, our cultural, political and material realities in ways that we must critically analyse and understand if we seek to liberate ourselves and our peoples.

HA: As an African feminist based in the university, where have you found the challenges and opportunities between feminist activism and academic spaces?

Prof. Amina Mama with African Feminists Simidele Dosekun, Prof. Abena Busia, Dr. Margo Okazawa-Rey, Prof. Sylvia Tamale, Harlem 2014

Amina: Identifying as both feminist and African is an act of resistance that provokes both patriarchal and imperialist reflexes in most of the systems and institutions we encounter in the course of our lives and careers. Because no institutions exist outside of societies, all are imbued with patriarchal power relations, so all are also justifiable sites for struggle.

The university–despite its pretensions and universalizing claims – is therefore just another site of struggle, whether we are talking about the institutional structures and cultures of the academy, or the work it does to school and train successive generations. The university to my mind is a strategic location that must be de-mystified and liberated from its histories of complicity with elite interests because it is an important site for the reproduction – or transformation – of hegemonic ideologies and values, as well as for the technical know-how and skills. They tend –unless interrupted – to be conservative, androcentric institutions that reflect hegemonic ideologies and legacies of imperialism, class-ism, racism, sexism and so on. While the name suggests a degree of “universalism”, universities are actually parochial institutions, which means that while the system has general features, each is infused with its own localized traditions and institutional culture. However, universities also have histories of struggle –especially evident in feminist women and gender studies, and in some places, ethnic studies. These fields can be understood as ongoing efforts to purge the colonial-patriarchal legacies that permeate the structures of the academy. . The shifting naming of ‘women’s studies’ to ‘gender and women’s studies’, to ‘feminist studies’ reflects the fact that feminist interventions in the academy are continuously being appropriated and depoliticized, only to be re-charged by energy surges in the movements that they have come out of. Maintaining the radical features of feminist thinking is an ongoing struggle that requires a lot of careful pedagogic and methodological strategies and against-the-grain intellectual work. Feminists in the academy have a tough time resisting both divestment and de-radicalisation. As a result programs and departments for the most part remain precarious. I was surprised to find that this is not only the case in African contexts where we have fought long and hard to establish about 40 programs, but also in the US context where they have over 600 programs, but it seems to me that most have been kept on the defensive: under-resourced and threatened for over 30 years, no matter how successful they have been! Feminists in such places become accustomed to inhabiting the margins, quietly working away in interstitial spaces between and across disciplines and departments, but having profound and often transformative effects on their students.

While I was working with colleagues at the African Gender Institute (AGI) in the early post-apartheid years, from 1999-2009, we developed three main strategies of engagement. The first was to resist the racist and imperialistic tendencies of early post-apartheid South African academic culture by insisting on working to create collaborative spaces that could be occupied by feminist scholars from all over Africa, and then protecting these from being overwhelmed by the eager beneficiaries of apartheid and Western domination. The second was to insist on locating our teaching and research as an integral aspect of feminist movements on the African continent, and finding ways to support one another in the face of the competitive individualism that is associated with career success in the academy. The third and most subversive strategy emerged by default. When the already challenging environment of a historically white university became increasingly unfavorable in the context of higher education reforms, the initial vision of institutionalizing a continental resource that could accredit and support feminist teaching and research all over the continent simply became unrealizable. We therefore found ourselves relying on a feminist strategy of intellectual networking, convening curriculum development and research projects dispersed across multiple locations in East, West and Southern Africa, instead of staying to build a feminist ‘centre of excellence’ that would, in retrospect, probably have been more vulnerable to the intensifying constraints of a University embracing neoliberal reforms, even as it proclaimed its transformation. The very minimal core funding from our institutional home meant that we had to take on the challenge of raising external funds for this kind of work, and then carry it out as overload –on top of the regular faculty load. We had insane schedules, but the energies of feminist movements – and our connections with these – only motivated us further. In the end our activities were tolerated, despite being subjected to endless reviews, and retrograde efforts to absorb and ‘normalise’ the AGI as a conventional academic department, which would not be as capable of carrying out feminist projects across the continent.

HA: You are the founder and editor of the seminal journal Feminist Africa, in which both eminent and emerging African feminist scholars are published, and from which African feminists have and continue to contend and define African feminist thought for ourselves at the juncture of praxis. Can you tell us more about this endeavor? What was the inspiration? What have been the achievements and challenges?

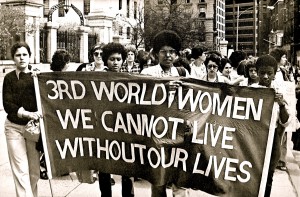

Amina: In 2002 Feminist Africa (FA) was established in response to the collectively-articulated need for an independent political-intellectual publication in which feminists across the continent could critically engage with one another to support and strengthen feminist praxis, and publish scholarly work that is afforded very little space in the existing Western-based feminist journals, where our work is subject to norms and gatekeeping practices that only allow occasional publishing of individual articles by a few established individuals (including at that time, women like myself who were already professors). FA is therefore designed to share, respond to and inform feminist theorizing, strategizing and activism that centres African realities and feminisms. We set out to intervene in a world still set up to treat African women as raw material for the projects of others, while theory was the preserve of white and Western women, despite the critiques of Awa Thiam, Omolara Ogundipe-Leslie, Nawal El Sadaawi, and many others who joined AAWORD from the early 1980’s on. In the West Black and Third World feminists like those in the Combahee River Collective (from 1974), Angela Davis (1982, 1984), Hazel Carby (1982), bell hooks, and Chandra Mohanty (1989) were challenging the academy around the same time.

Demonstration in Boston after murders of Black women, led to creation of the Coalition for Women’s Safety, 1979. Photo by Tina Cross

Feminist intellectuals in Africa have to deal with the fact that our writing and research is seldom respected in the African academy. And while there are many women’s movement publications and reports coming out of movement organizations, back in 2000, when we began to plan FA, there wasn’t an African gender studies journal, let alone one that would treat academic work as a valid mode of activism. On the other hand activists tended to be dismissive of intellectuals, in part because most academic work is not informed by activist concerns, and not accessible to a wider readership. We wanted to subvert the institutionalized elitism that would keep all that passes for ‘theory’ separate from the ‘real world’ of practice, clearly something that undermines feminist agendas. FA is grounded in key principles: activism, and critical reflection on activism, generates knowledge and insights that can inform and strengthen our liberation struggle; activism is more effective when it is grounded in sound analysis of the conditions we seek to change and theory offers useful tools for analysis.

FA is now over a decade old and we are currently editing issue 20, but of course there have been a great many challenges along the way. However, for anyone who take dialectical materialism seriously, each challenge is also an opportunity to learn and move forward. For example, FA has not had core funding to date, so “free” means relying on ”free labor”, which draws the most dedicated and serious feminists in to keep it going. Keeping it open access and online, and distributing free hard copies to the network of feminist scholars are commitments that make FA unacceptable to the monopoly publishing houses that absorb most academic journals, so we have resisted overtures that would compromise that, even though they would offer funding and greater security. The downsides of that political position are that FA remains uncertain of its future. . The upside is that each issue being a unique adventure in collaboration and commitment, and proves we can mobilize feminist energies and skills, and we are not necessarily subject to the vagaries of funders and their annoyingly neoliberal fads. This in turn ensures a high turnover that might be hard on the editors, but is more inclusive.

FA keeps going without core funding, but in addition to the labours of the feminist African network the fact is that the AGI has been able to host it consistently for over 12 years. My colleague Jane Bennett and I have spent a lot of energy reaching out and trying to mobilize the financial resources to make FA more sustainable. The original plan was that it would rotate around key feminist sites in African continental universities, but so far other centres have not felt they had the resources or personnel to take it on. However, the fact that it is surviving is a powerful testament to the power, energy and dedication of the feminists who have worked with us on it, as most of the editing work remains entirely voluntary. I suspect that over the years, while funding has become harder, we’ve become stronger in the sense that we seem to have built a sense of collective ownership among the geographically dispersed community of African feminists. In concrete terms, to keep it coming out twice a year we outreach to recruit and draw new people in for every issue, some of whom have worked on several issues over time. Following a period of fatigue – and my own relocation , I’d like to appreciate the various feminists –including you, Hakima – who’ve joined the FA community as guest editors and co-editors, to see particular issues through. Currently I’m much more optimistic that some of the conversations I’ve had with possible partners will yield the right kind of support in the near future, so that we can keep FA alive and uncompromised, as we systematize and strengthen its editorial and production processes in ways that will ensure its continuation for the coming decades.

HA: Much of your work in the last decade has focused on the pervasive gendered impacts of militarism in Africa. What led you to this work? What are these impacts?

Amina: Living and growing up on the continent, it would be hard not to realize the enormous costs that militarism and conflict exact on Africa’s people. As feminists we pay particular attention to violence against women because this is such a central feature of women’s oppression in peace, as well as during conflict, and in post conflict societies. When we reflect on the history of the continent, it becomes clear that militarism and conflict are an integral part of the machinery that sustains the underdevelopment of our continent. Following often-violent colonization and the establishment of colonial regimes and colonial armies, hundreds of thousands of African men were conscripted and otherwise drawn into the 1st and 2nd world wars. These men – trained and experienced in killing and warfare on an industrial scale – returned to the continent to participate in the establishment of male-dominated states that retained their armies as a key feature of the new nations, some even expanding them, even as the world wars were giving way to the so-called “Cold War”. Needless to say this was not cold in Africa that was now caught in the East-West ideological split. Our military men, backed by competing foreign powers, embarked on a rash of power struggles and military coups that stalled the de velopment of democratic systems. By the mid 1970’s more than half of Africa was governed by military rulers, and in the worst scenarios these established dictatorial and parasitic states that were better at preying on their citizens than protecting them. The figures on African military expenditure show how many nations have spent vast sums – that account for much of the accumulated national debts – instead of securing all of us by establishing political and economic systems that would ensure the establishment of the health, education, legal and welfare systems essential to the well being of the people, and surely to any understanding of ‘development’. Development is about people, not guns. No amount of military power can bring about security in the absence of food, water, healthcare, affordable energy, decent work and a decent environment – all those things that have been enshrined in over half a century of lofty declarations, but which remain elusive in the former colonies. Needless to say surveys confirm that women do define security differently from men – not in terms of all-male armies and arsenals of weapons, or even in terms of national border policing– but in terms of security from poverty, and epidemics of disease, in terms of freedom from violence and the fear of violence. Women –whose bodies are so often abused by men to spite other men – define security in terms of bodily integrity, that is freedom from violence, abuse and exploitation. For us rape is not just a ‘”weapon of war” but an endemic feature of our unjust and patriarchal societies, where misogyny lives in peacetime as well as in war-time. Look at the prevalence data on violence against women not just in Africa, but worldwide.

velopment of democratic systems. By the mid 1970’s more than half of Africa was governed by military rulers, and in the worst scenarios these established dictatorial and parasitic states that were better at preying on their citizens than protecting them. The figures on African military expenditure show how many nations have spent vast sums – that account for much of the accumulated national debts – instead of securing all of us by establishing political and economic systems that would ensure the establishment of the health, education, legal and welfare systems essential to the well being of the people, and surely to any understanding of ‘development’. Development is about people, not guns. No amount of military power can bring about security in the absence of food, water, healthcare, affordable energy, decent work and a decent environment – all those things that have been enshrined in over half a century of lofty declarations, but which remain elusive in the former colonies. Needless to say surveys confirm that women do define security differently from men – not in terms of all-male armies and arsenals of weapons, or even in terms of national border policing– but in terms of security from poverty, and epidemics of disease, in terms of freedom from violence and the fear of violence. Women –whose bodies are so often abused by men to spite other men – define security in terms of bodily integrity, that is freedom from violence, abuse and exploitation. For us rape is not just a ‘”weapon of war” but an endemic feature of our unjust and patriarchal societies, where misogyny lives in peacetime as well as in war-time. Look at the prevalence data on violence against women not just in Africa, but worldwide.

Many of us have direct or indirect experiences of war, conflict and military rule. The appalling consequences this has for our societies and for future generations has compelled many women to work for de-militarization and peace. This was evident in the work of the women’s movements in Liberia and Sierra Leone, where women played key roles in ending disastrous conflicts during which men specifically targeted women’s and children’s bodies for rape, mutilation and other violations designed to terrorize ordinary people. Women’s movements continue to work against the long-term social and economic consequences of war and other violent attacks on communities, in ways that deserve far more support than they are currently getting.

In my particular case, I think my anti-militarism goes all the way back to my earliest recollections of the Nigerian civil war, to the assassination of the Sardauna of Sokoto and the anti-Igbo pogroms in Kaduna at the end of the 1960’s. I think all Nigerians have been profoundly affected, as the war was followed by a series of other coups, and over 3 decades of military rule. My entire generation grew up under military dictatorship, witnessing the everyday ramifications of this –in all the inequalities and injustices that characterize militarized societies, and their effects on our already-gendered (post)-colonial cultures and sexual politics. Lately, even with a civilian government, we are dealing with these legacies, in the form of unjust gender policies that have re-introduced the child marriage, tried to force dress codes on women, and widespread violence against women. There are now many other forces of violence in Nigerian society, variously manifesting as ethnic, religious, or resource conflicts, and violence against women and girls remains endemic. My analysis is that this is a function of corrupt authoritarian regimes,characterized by extreme patriarchy – and this manifests in everyday misogyny, the policing and scapegoating of women, and high tolerance for violent abuse of women.

More generally, the long-term effects of militarization and military rule persist even after civilian governments are established. Politics tend to be violent, as competing interest groups organize gangs of thugs to secure elections; protests against dispossession are met with military force, which in turn leads to the militarization of people’s struggles for justice. The Niger Delta is an obvious example, but so are Sierra Leone, Liberia, the DRC and other conflict sites. Numerous manifestations of organized violence have created a situation in which the state no longer holds its traditional monopoly on the use of force. In these days of globalization and the liberalization of trade, the violent suppression of small insurrectionary groups can rapidly escalate to become identified as threats to global security, as we have seen with Boko Haram. War-making has remained a highly profitable, self-perpetuating industry, that serves transnational corporate interests over those of human security in mineral rich zones. The concomitant erosion of the non-military aspects of the state – education, health and welfare services – are so weak that governments are apparently unable to prevent or control epidemics. Think about today’s situation. We now have to rely on the military – and the US military at that – to address the Ebola epidemic, because of the inadequacy of health services and the infrastructure that would enable them to operate more effectively, and the Western-based healthcare NGO’s trying to provide emergency responses are not-surprisingly overwhelmed. I was interested to see that Cuba sent 600 medical personnel, not soldiers. It is time the Western powers that have pursued the global divestment of the public sector stopped pretending that “market forces” and charities can replace the socio-economic responsibilities of government. Neoliberal policies are retarding the historical progress towards democratization, and hampering the best efforts of our societies and movements to bring about the deeper systemic change that progressive movements are currently demanding. That is why we see social struggles: women’s protests, labor strikes, public demonstrations, the recent occupy movement, and the multiple uprisings all over Africa. These are all resisting the abject condition created by the rapacious manifestations of capital that have dominated post-colonial conditions. Less palatable examples of dissent can be seen in the religious and ethno-nationalist formations that appear to define post-colonial conflicts. Yet all of this is ultimately about poverty, underdevelopment and access to resources – it is these material conditions that lie at the base of our insecurities, creating and sustaining our proclivities for violence.

HA: From whom do you draw your own inspiration?

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (1900–1978) was a leader of Nigeria’s anti-colonial struggle and founder of the Abeokuta Women’s Union

http://en.unesco.org/womeninafrica/#sthash.RUy3LECz.dpuf

Amina: That’s a hard question! I can name a number of individuals – men as well as women that have inspired me along my path, but the most important source for me has been the feminist activists and women’s movements that I have been privileged to work with in various African contexts. These include local communities in and around the West African terrain where I grew up, particularly sister-comrades in Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal. I have also been inspired by feminists in Uganda, Kenya, Egypt, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and in South Africa, where I lived for almost a decade. However, my exposure to a rich array of African and Western contexts, and my long term interest in women’s herstories and experiences mean that my favorite individuals come from all over Africa and beyond. You want some names? Early in my life, Hajiya Gambo Sawaba and Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti stood out as two of Nigeria’s most courageous activists, while the legendary Queen Amina of Zazzau inspired some of my best fantasies. I think I was about 12 years old when I saw Angela Davis walk out of prison on the international TV news in our living room in Kaduna, and she has stayed high on my list. When I joined the Marxist-feminist Black Women’s Group in Brixton in 1980, Claudia Jones captured my heart and my imagination – both re-ignited recently, when I read Carole Boyce-Davis’ ‘Left of Karl Marx’ earlier this year. I take great pleasure in introducing my students to these women, as well as to Huda Sharaawi and Doria El Shafik of Egypt, along with many other feminists that have fought for freedom throughout recent history. Nowadays I draw much of my inspiration from younger feminists I encounter in the course of travels – many of whom are brilliant writers, critical thinkers and activists. As a teacher I have the privilege of working with students. I admire the next generation for finding the courage to embrace radical politics in today’s world, for choosing to develop critical intellectual abilities and skill sets that are more about subverting than surviving an unfavorable global market. I admire their resistance to cynicism and their enthusiasm for facing a less-than-certain future that presents more complex challenges than any of my generation, or my parents’ have had to face.

3 Comments