Criminal Fashions: The Hermeneutics of Hip-Hop Aesthetics

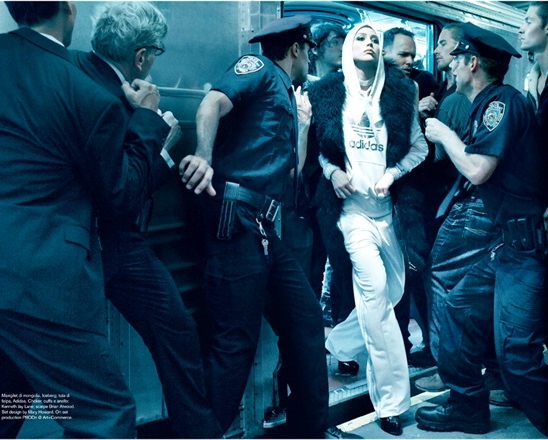

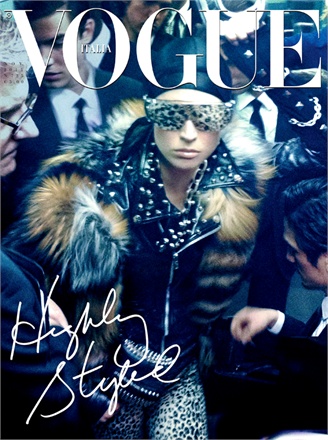

The hip hop aesthetic has recently made its way to the cover of Vogue Italia, one of the most influential magazines of the fashion world. A white female model, dressed in a studded motorcycle jacket, a fur collar, and a du-rag, is positioned on the cover of the November issue. Other female models are captured posing on the subway in extravagant outfits that range from the excessively spiked aesthetic of punk subcultures to the classic opulence of Jackie Kennedy Onassis. The models, who look like they stepped out of a hip hop video from the past two decades, or, perhaps, onto the subway platform from one of the Black and Brown communities that the A train services, are situated in photos within the editorial piece that accompanies the cover photo, “The A Train.” Satirized female bodies are depicted donning an array of hip-hop wears: long, bejeweled nails; black du-rags; bright scarf wraps; fitted caps; doorknocker earrings; large, chunky gold chains; and Adidas track sweat suits.

I had mixed reactions to the editorial as I tried to make sense of the cultural appropriation at work. Part of me was happy that the cultural creativeness of Black and Latino people from cities throughout America was being celebrated and legitimized in the high fashion world. Still, such celebrations come with very real ethical considerations in that the communities in which the sartorial aesthetic originated and are cultivated—in the thoroughfares of Black and Brown communities from NYC to Los Angeles—remain economically deprived, and will likely not receive any material benefits from the “celebration” (and, commodification) of Black, urban culture in Vogue’s piece.

In the present global economic and geopolitical contexts, local and national boundaries are porous: culture productions are trafficked between and amongst communities around the world. In the American context, in which racial and economic boundaries (past and present) govern mechanisms of cultural exchange, appropriation has been largely one-sided and has become synonymous with exploitation. Indeed, cultural artifacts are re-signified based on the corporeal and spatial geographies from which they emerge. The different ways in which certain bodies are valued based on race, gender, and location belies the presently operating de facto racial and gender codes in a supposedly post-racial country. I am reminded of this reality daily on the campus of Stanford University where many white male students can be seen donning sagged jeans, fitted hats, and basketball sneakers reflecting a cool and edgy but safe heterosexuality. Less than five minutes away in East Palo Alto, or further away in Oakland, the same clothes on Black and Brown men signify a criminal threat that warrants state intervention and, possibly, death.

In some environs, and when signified per certain raced and gendered bodies, hip-hop fashions function as a marker of social ineptitude, moral deficiency, and deviance. When worn by Black and Brown cis and transgender women and men from low-income locales hip hop fashion is a signifier that affects one’s ability to find gainful employment, live without state scrutiny, and/or outside of prison cells. The quality of life (or life itself) of those who inhabit spaces characterized by skin and class privilege are not subject to such severe consequences by their decision to wear certain styles of clothing.

Vogue Italia may not have had any harmful intentions with the publication of its editorial piece; yet, the appropriation of the urban streetwear aesthetic appears as a mockery when those same fashions subject other people to policing, surveillance, harassment and death. By no means do I suggest that certain people should have the license to wear particular stylized clothing only, but, rather, I seek to illuminate the fact that fashion exists within specific historical, political, and cultural contexts that cannot be ignored. The truth is: White female bodies on the covers of magazines might escape criminalization in ways that Black and Brown bodies positioned on the A train may not. A palpable irony and amnesia haunts the editorial piece in that the Black and Brown folk who inhabit Brooklyn, fashion themselves in hip hop clothing, and frequent the A-Train are nowhere to be seen. Perhaps it is a visual metaphor of the gentrification currently at work in Brooklyn.

_________________________________________

Kiyan Williams hails from Newark, NJ. He is an undergraduate at Stanford University.

Kiyan Williams hails from Newark, NJ. He is an undergraduate at Stanford University.

12 Comments