Hoods Up, Hands Up: Against the White to Bear Arms

By Lauren Heintz

The images of militarized police in Ferguson rightly bring to mind the trickle down of military devices to state police, as Rania Khalek argues in her article. They also call up a much deeper historical legacy of how and why state police have always been heavily armed. In the late eighteenth century, armed militias were created specifically for white Southerners to defend against slave revolts, in which slave patrols “made sure that blacks were not wandering where they did not belong, gathering in groups, or engaging in other suspicious activity.”[1] Today, in the streets of Ferguson, police are claiming that protestors are wandering where they do not belong after dark, evoking histories of “sundown towns,” protestors are gathering in groups, reminding us of the deep rooted fear and suspicion slave owners had of enslaved peoples assembling at any time. Mike Brown jaywalking with a friend was a suspicious enough group activity that ended his life.

So why are state police armed? Patrick Henry, plantation owner and Governor of Virginia in the 1770s, appealed for the second amendment to become a state governed, rather than nationally controlled, right to equip a militia with arms: “ ‘If the country be invaded, a state may go to war…If there should happen an insurrection of slaves, the country cannot be said to be invaded.’ ”[2] Patrick Henry was worried that if the right to bear arms were governed by a national militia, there would be nothing stopping Northern abolitionists from enticing enslaved people to run away and join the northern army. This, after all, happened during the Revolutionary War. The state controlled right to bear arms was passed specifically to keep slavery intact, to protect plantation owners from inside threats of slave revolts.

On August 18, 2014, President Obama’s statements on Ferguson, despite his perhaps best intentions, invoked the same cover, asserting that state police are given increased weaponry to protect against an invasion from outside “terrorist” forces. Dating back to Patrick Henry’s historical claim, we know that national security is not why state militias are armed. In 1789, state militias were armed for white localized security in the form of slave patrols that regulated the threat of slaves in the South. In 2014, state police are armed in the form of a snipers on top of military trucks, to “contain” the unarmed Ferguson protestors. The notion of an “outside threat” has always been a smoke screen.

Getty Images, Scott Olson: http://www.vox.com/2014/8/14/6002917/ferguson-police-expert-interview-fritz

It is clear that the right to bear arms is, plainly, the white to bear arms. The state’s national guard is being deployed in Ferguson, but it was not deployed at the Bundy ranch earlier this year.[3] When the Nevada group of armed white men and women engaged in a stand-off with state police, the police did not fire tear gas or rubber bullets. They backed down. As Rachel Maddow reports, the Bundy stand-off also had its roots in Southern racist politics. During reconstruction, the Southern militia was bent on driving out, yet again, the Northern troops. This time the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act was passed: state militias yet again trumped Northern federal troops. The Union’s withdrawal from the South directly brought about the legalization of Jim Crow violence. Cliven Bundy has ties to the contemporary white supremacists Posse Comitatus militia.

Jim Urquhart/Reuters: http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/04/the-irony-of-cliven-bundys-unconstitutional-stand/360587/

Last week as well, John Crawford, a 22 year old African American man, was killed for carrying a BB-gun in a Walmart. Earlier in 2014, white open-carry NRA fanatics brandished weapons in Walmart, among other places. Open-carry NRA members can argue with police when asked to show ID, or when asked to leave the business establishment. Being asked such questions is not a luxury given to unarmed black men. Putting up unarmed hands was not an option for John Crawford or Mike Brown last week, or for the numerous other black men and boys killed; or for black women: Dr. Ersula Ore, assaulted by police for jaywalking; Marissa Alexander, on trial for firing a warning shot in self-defense; Renisha McBride, shot and killed when asking for help on a white man’s lawn.

To take into account the historical legacy of the white right to bear arms is to insist that we remember that the second amendment is, quite literally, shot through with Southern militia slave patrols, with reconstruction era Jim Crow violence, with state-armed police, with white supremacist Posse Comitatus members.

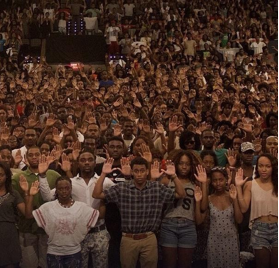

Protests that echo within and beyond the streets of Ferguson confront this legacy. We have our hoods up for Trayvon Martin, and we have our hands up for Mike Brown. We stand up for justice and for peace. We hold each other up with arms raised, voices raised. We remember that stories of resistance, too, are written into history. We trace this history to Toussaint L’Ouverture, Nat Turner, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Jacobs, and to unnamed and unrecorded acts of resistance. These protests aren’t ugly, they are organized and spontaneous expressions of emotion and intellect: dancing in the streets, playing music, yelling in outrage, marching with conviction, finding the uses to one’s anger (to invoke Audre Lorde).

Each of these instances of standing up, hoods up, hands up, is a collective moment of historical significance. It is one that recalls a passage from one of the greatest fiction pieces of black resistance from the nineteenth century, Martin Delany’s Blake, or the Huts of America (1859):

“Some were merry, others sad – some joyful, others mad; some discouraged, others encouraged – some hopeful, others despairing. Among the disappointed should be considered the restless American part of the inhabitants known as ‘patriots’; the sad and hopeful were the black and colored people who had determined to manage in future their own affairs; there were among this portion of the inhabitants those who determined that for the last time they had looked with passiveness upon the sad scene of trained bloodhounds upon the living flesh of their kindred and sporting in luxury on the misfortunes of their race. Whilst reflecting upon these scenes with a sad and heavy heart, they could only discern before them a dark and gloomy pathway, which but now and again was lighted up by the sudden outbursting of a concealed flame, deeply hidden in their breast, flashing as they passed along. But they had one encouragement – a faint, steady light away off in the distance – discernible through the obscurity of space – the Star of Hope – whose cheering rays had reached them, encouraging them onward in their slow but steady march” (246).

The ending of Blake is unknown, its full manuscript was never recovered. The ending of the Ferguson protests and Mike Brown’s legacy are unknown to us now. But what is known is that “the sad and hopeful” of those then and now are “determined to manage in future their own affairs,” flaming forward in “their slow but steady march.”

Megan Sims, Howard University: http://www.buzzfeed.com/krystieyandoli/why-howard-university-students-took-this-photo-in-solidarity

[1] Carl Bogus, “The Hidden History of the Second Amendment,” UC Davis Law Review 31.2 (1998): 309-408.

[2] Thom Hartmann, “The Second Amendment Was Ratified to Preserve Slavery,” Truthout (2014). <http://truth-out.org/news/item/13890-the-second-amendment-was-ratified%20-to-preserve-slavery>.

[3] Others have recently drawn attention to the disparagement in police response between Ferguson and Bundy: see Brad Friedman, “Cliven Bundy vs. Ferguson’s peaceful demonstrators: A tale of two protests,” Salon.com (2014) <http://www.salon.com/2014/08/18/cliven_bundy_vs_fergusons_peaceful_demonstrators_a_tale_of_two_protests/>.

___________

Lauren Heintz is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Literature at the University of California San Diego, and is a Mellon/ACLS dissertation fellow. Her research and writing focus on nineteenth century U.S. literature, specifically African American literature and gender and queer studies.

Lauren Heintz is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Literature at the University of California San Diego, and is a Mellon/ACLS dissertation fellow. Her research and writing focus on nineteenth century U.S. literature, specifically African American literature and gender and queer studies.

2 Comments