Personal is Political: How Assata Shakur Changed My Life: The Importance Of Ethnic Studies Curricula In High School And Beyond

By Tala Khanmalek

Dedicated to Miss Sonja Roberts.

“I have been locked by the lawless.

“I have been locked by the lawless.

Handcuffed by the haters.

Gagged by the greedy.

And, if i know anything at all,”

it’s that a wall is just a wall

and nothing more at all.

It can be broken down.

I believe in living.

I believe in birth.

I believe in the sweat of love

And in the fire of truth.”

-Assata Shakur

I read Assata by Assata Shakur when I was 14 years old and it changed my life forever. Her autobiography offered me a historical context for my experiences and those of my immigrant family that I was not learning about in school. Most importantly, it offered me a critical vocabulary—of terms like racism, oppression, liberation, and revolutionary—to name what I had been feeling, but had no words to describe. It was through Shakur’s story that I began to connect the dots and understand our struggles as Iranians in America comparatively. Situating our selves in relation to others across racial and ethnic groups had a profound impact on my identity formation that has determined the course of my work ever since.

During my second year of high school in 2003, the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District declared a moratorium on the receipt of all inter-district attendance permits. The California educational system relies on “local control” for the management of school districts. There are residency requirements for school attendance in every district that have become increasingly restrictive. The ban on inter-district permits was a fundamental shift towards regulating access to public education based on neighborhood, further excluding students of color from East LA and parts of West LA such as Culver City. I was one of many students who lived within the boundaries of the Los Angeles Unified School District, but attended Santa Monica High School (Samohi) instead. To do so legally, my mom applied for an inter-district transfer using the address of a family friend. At the risk of penalty and to her own maternal discredit, she courageously claimed that our family friend was my mother so I could graduate from a high school that would increase my chances of college admission.

The transition from Palms, my neighborhood in the Westside region of Los Angeles County, to Santa Monica was a daily challenge. In West LA, Palms is a highly diverse area, especially in comparison to Santa Monica, which is predominantly white and upper class. Once deemed undesirable by middle to upper class residents, Palms and its neighboring communities—Culver City in particular—are now ideal places to live for transplants. Longtime residents including my own family, many of who are working class, have been displaced and replaced by Sony Studio and other high-paid corporate employees due to the rising cost of living. When I was attending high school in the early 2000s, gentrification was still underway, making the differences between communities more visible. I felt out-of-place at Samohi, whose student body reflected that of the beachfront neighborhood. I was accustomed to seeing mostly people of color in public as well as immigrant owned and operated businesses that served the local demographics. I loved being in Palms and rarely ventured into other neighborhoods that, blinded by my own privileged position, I didn’t realize were systematically segregated from ours. Needless to say, attending high school in another—whiter and wealthier—district exacerbated my identity crisis, and because inter-district permits were banned right after I started, Samohi was becoming less and less diverse than it already was.

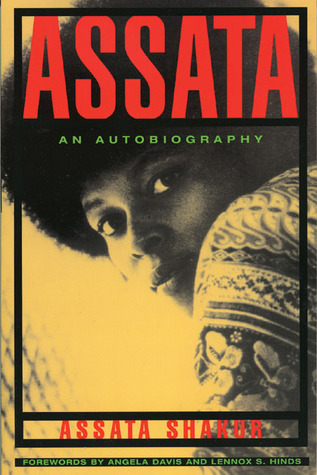

By some stroke of luck I was assigned Sonja Roberts for English during my freshman year. Miss Roberts, who also taught an optional African American Literature class for seniors, must have been one of a handful if not the only woman of color faculty member at Samohi. Samohi also offered an optional Chicano Literature class for seniors. I still don’t know who instituted this program but the Board of Education just approved an Ethnic Studies program for the high school this year. When I confided my sense of alienation to her, she listened and handed me the syllabus for African American Lit. At age 14, I was reading everything from Anna Julia Cooper’s 1892 A Voice from the South to Rebecca Walker’s then hot-off-the-press Black, White, and Jewish (2002). One by one I borrowed her copy of the books her seniors were reading either right before or right after she used it to lecture, beginning with Assata (1987).

In her autobiography Assata Shakur chronicles her false indictment for a number of crimes, including murder, as an active Black Panther Party (BPP) and Black Liberation Army (BLA) member in New Jersey. After a series of corrupt trials and years of incarceration at various prisons throughout the 1970s, Shakur escaped in ’79 unlike the majority of political prisoners. A “20th century escaped slave,” as she famously calls herself, Shakur was granted political asylum in Cuba where she currently lives. She published her autobiography soon after and has written many web-publications since then. She has also co-authored Still Strong, Still Black with Dhoruba Bin Wahad and Mumia Abu-Jamal in 1993. Her story has been and continues to be the subject of documentary films, most notably Gloria Rolando’s Eyes Of The Rainbow, Hip-Hop songs, scholarly articles, and global campaigns such as Hands Off Assata. Last year she was added to the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorist List, the first woman and second domestic terrorist, for crimes she was convicted of 40 years ago.

Yet it wasn’t just Shakur’s story that impacted me, it was the way she wrote it. She seamlessly weaves the story of her childhood in North Carolina, marking the moments that shaped her political consciousness and led her to join the BPP and the BLA after college. Combining multiple literary genres from poetry to prose as well as excerpts from official documents like her own trial transcripts, Shakur strategically and creatively plays with form to tell a story that is at once personal, political, and pedagogical. Her autobiography expanded the possibilities of expression for me at a pivotal time in my life when language itself seemed to betray the integrity of my young voice.

In 2004, Samohi administrators ordered a lockdown on the pretext that “racial tensions” between black and Latino students caused violence on campus. No one was allowed to leave the premises during lunchtime, which were patrolled by police officers in addition to security guards. The shallow discourse of racial tensions blamed students of color for issues far beyond our high school. According to the census, the number of Santa Monica’s black and Latino residents had been in decline since 1990 and those who remained were continuously segregated in the Pico Neighborhood. Thanks to Miss Roberts, we had the conceptual tools to see through the dominant narrative of the district.

Since we were confined to campus, she facilitated discussions about the lockdown in the Art Studio specifically for students. Amy Bouse, the art teacher, truly cared for students at Samohi and always let us to take refuge in her classroom or the Art Studio. She was an ally and a fearless advocate who treated us as equals and supported our creativity. She encouraged us to apply what we learned in African American Lit (which I was formally in by this time) to current events, highlighting similarities and differences between the past and the present. As she helped us develop our intuition and our intellect through the specific legacy of African American Lit, we naturally extended our critiques (trans)nationally, just like the writers we read. In 2005, we organized a protest against the war in Iraq that started on campus and ended at the Federal Building. Such is the powerful impact of an Ethnic versus exclusively Euro-American Studies curriculum not only in higher ed, but especially in primary and secondary school. It teaches all students how to change the world beginning with their own lived experience, privileging multiple perspectives on history instead of one universal Truth. It is no wonder that Ethnic Studies is under nationwide threat and banned in Tucson schools. Classes like African American Lit treat education as it should be treated in every discipline at every level of study: a source of empowerment in the service of social justice.

_________________________________________________________

Tala Khanmalek is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley with Designated Emphases in Critical Theory and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. As the former Executive Editor of nineteen sixty nine she published the latest issue entitled “Healing Justice” featuring Aurora Levíns Morales (available here). She is the founder and director of the UC Center for New Racial Studies working group “Politics of Biology and Race,” as well as a creative writer and artist.

Tala Khanmalek is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley with Designated Emphases in Critical Theory and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. As the former Executive Editor of nineteen sixty nine she published the latest issue entitled “Healing Justice” featuring Aurora Levíns Morales (available here). She is the founder and director of the UC Center for New Racial Studies working group “Politics of Biology and Race,” as well as a creative writer and artist.

Pingback: How Assata Shakur Changed My Life: The Importance Of Ethnic Studies Curricula In High School And Beyond | Moorbey'z Blog

Pingback: How Assata Shakur Changed My Life: The Importance Of Ethnic Studies Curricula In High School And Beyond | Alice News