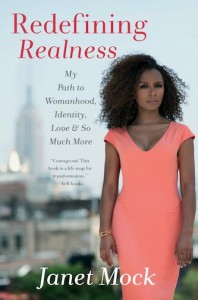

Redefining Realness by Janet Mock (Book Review)

By David B. Green, Jr.

I have learned through the process of story telling and sharing that we all come from various walks of life and that doesn’t make any of us less valid.

–Janet Mock

To date, there exist only a select number of memoirs written by self-identified Black trans or drag-queen men and women. Amongst these few, they all have rendered narratives that offer public glimpses into their private lives and how, against all odds, they managed to find personal happiness, career success, and love. In 1995, Ru Paul served us with his memoir, Letting It All Hang Out and over a decade later, in 2010, he published Workin’ It: Ru Paul’s Guide to Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Style. In the same year that Ru Paul publishes Workin’ It, Miss J. Alexander—the former infamous runway coach of Tyra Banks’s America’s Next Top Model—published Follow the Model: Miss J’s Guide to Unleashing Presence, Poise, and Power. In their various formulations, these memoirs engage in acts of story-telling and memory-making that both titillate and humor our senses as they wittingly and provocatively challenge readers to confront and expand their notions of not only blackness, or queerness, drag queendom, or feminine performance. As writers and visionary politicos they present us with questions to the meanings of freedom. Ru Paul, for example, signifies on “The Declaration of Independence” while Miss J. Alexander subtly reformulates black power rhetoric, unleashing this power against traditional scripts of black masculinity—“presence and poise.”

To date, there exist only a select number of memoirs written by self-identified Black trans or drag-queen men and women. Amongst these few, they all have rendered narratives that offer public glimpses into their private lives and how, against all odds, they managed to find personal happiness, career success, and love. In 1995, Ru Paul served us with his memoir, Letting It All Hang Out and over a decade later, in 2010, he published Workin’ It: Ru Paul’s Guide to Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Style. In the same year that Ru Paul publishes Workin’ It, Miss J. Alexander—the former infamous runway coach of Tyra Banks’s America’s Next Top Model—published Follow the Model: Miss J’s Guide to Unleashing Presence, Poise, and Power. In their various formulations, these memoirs engage in acts of story-telling and memory-making that both titillate and humor our senses as they wittingly and provocatively challenge readers to confront and expand their notions of not only blackness, or queerness, drag queendom, or feminine performance. As writers and visionary politicos they present us with questions to the meanings of freedom. Ru Paul, for example, signifies on “The Declaration of Independence” while Miss J. Alexander subtly reformulates black power rhetoric, unleashing this power against traditional scripts of black masculinity—“presence and poise.”

Janet Mock’s memoir, Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More also compels readers to question and revise accepted concepts of freedom as she discovers how this concept applies to her own life as a trans woman of color in a U.S. polity hell-bent on blatantly, and sometimes clandestinely, ensuring trans and queer folks’ total demise; for after all, given their black queer fem subjectivities, they too, were never meant to survive. Stated differently, Mock’s memoir represents a freedom narrative that does more than just recall a story of a trans woman’s journey to self-actualization, happiness, and love. We might say that in a Foucauldian sense the memoir’s narrative arc is structured as a “confession of the flesh.”[1] However, given the beautiful browness of her flesh, Mock’s concerns extend beyond Foucault—her textual authority deeply reflects an intellectual engagement with African American and women of color feminist literary traditions and it is through such traditions that we must interpret and value the memoir’s theoretical might and literary genius. By the end, Mock sketches an epistemology of womanhood where cis-gender women of color writers, every-day women, and trans women activists collectively inspire her growth, politics, and self-actualized womanhood.

Mock begins Redefining Realness by prefacing it with a disclosure about truth and specifically how she, as a writer, deliberately and rightfully exercises her agency to reclaim and write her herstory. “This book is my truth and personal history,” Mock declares in the memoir’s opening sentence (xi). A few pages later, Mock echoes black feminist Barbara Smith, writing: “We need stories of hope and possibilities, stories that reflect the reality of our lived experiences. When such stories exists, as writer and publisher Barbara Smith writes, ‘then each of us will not only know better how to live, but how to dream’” (xvii). Although Mock claims to share with readers aspects of her personal history, there is a degree of fantasy and romance that undergirds the text, which then allows Mock to creatively situate the memoir within a black feminist literary tradition: to produce “stories” that reflect the lives of people like herself. We could argue that Redefining Realness participates in the black feminist tradition of biomythography, remixing and blending fact and fiction where lived experiences and dream cultures share stories that circumvent and subvert established histories while simultaneously inventing new historicisms in the process. Unlike black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde, Mock does not directly claim her text as a biomythography. Yet, Mock relies on Lorde’s philosophy of self-definition to expand upon Simon de Beauvoir’s thesis that “one is not born, but rather becomes a woman” (171). Becoming a woman for Mock assured her that she had “the freedom, in spite of and because of my birth, body, race, gender expectations, and economic resources, to define myself for myself,” or risk being, she quotes Lorde, “crunched into other’s people fantasies for me and eaten alive” (emphasis in the original, 172). Thus, given Mock’s interest in “redefining realness,” the literary project of dreaming—and to a degree biomythography—offers her one method to deal with the pains of confession because “the dream is the truth,” she writes referencing Zora Neal Hurston (201). After all, Mock’s love for her partner Aaron inspires her confession and thus she would go on to “act and do things accordingly” (201).

After a few emotionally raw dates with Aaron, and after an equally emotionally intense night with him, Mock realizes that if she truly wishes to establish love with Aaron then she would have to confess aspects of her life that she, until then, kept quiet. “From a cavernous place, I reached inside myself and,” Mock remembers, “grabbed the courage to take a long trip back to a place I never thought I’d revisit. I took a deep breath and exhaled. ‘I have to tell you something’” (11). Mock’s confession doubles, however, as a revelatory act on the hand and on the other as an inter-textual narrative the relies on the power of women of color writing traditions; these traditions help to mitigate against the vulnerability of confession and facilitates a politics of critique that widens the representations and historical scope of womanhood.

Towards this end, Zora Neal Hurston serves as Mock’s principle literary muse. Hurston’s There Eyes Were Watching God (1937) constitutes the imaginative blue print from which Mock crafts her story. Indeed, Mock’s and Aaron’s meeting is a living manifestation of Hurston’s fictive characters Janie Crawford and Tea Cake. Mock prepares readers to engage a Hurstonian hermeneutic by engraving an untitled inter-chapter that presages her life in “New York, 2009” with a quote from Hurston’s critically acclaimed novel. The selected quote reads: “They sat there in the fresh young darkness close together. Pheoby eager to feel and do through Janie, but hating to show her zest for fear it might be thought mere curiosity. Janie full of that oldest human longing—self-revelation.” Like Hurston, Mock frames the poetics of revelation with the power of kisses, an act symbolic of the novels influence on a younger Mock who, like Janie, “yearned for true love.” For example, on their first date, Aaron tells Mock, “I think it’s time we kissed,” which slightly surprises Mock because such a gesture, she knew, would initiate the intimate process of truth-telling, which she feared. At that moment, Mock’s little secret induces anxiety that she believed would hurt something of an unexpected, though beautiful, beginning. However, it was their first sleepover that inspired Mock’s confession. After a night of movies the two eventually “kissed our way into my bedroom.” These were not just any kisses. They were, in Mock’s words, “freedom kisses,” uninhibited as they were, “by my self-conscious [and] over-thinking tendencies” (8).

Freedom kisses signal an intervention: liberation at the intersection of race and erotic desire. According to Mock, “Zora Neal Hurston wrote that Janie’s ‘soul crawled out from its hiding place’ when she met Tea Cake. I wanted to come out of my hiding place. I wanted a love that would open me up to the world and to myself. I wanted my own Tea Cake who wanted all of me” (5). Indeed, Mock’s love for Aaron however, forces her to challenge the love that she has for herself and her past, her “personal history.” Thus, Mock’s path to love is a bumpy road to a self-actualized womanhood; these literary inscriptions only buffer the bruises suffered on her sojourn of and for truth and “realness.”

Nevertheless, as Mock guides readers on a journey to womanhood that is both personal and intellectual, she makes a convincing case that womanhood and femininity are not mutually constituted. Femininity, Mock suggests, is an expression of gender, while womanhood implies an affirmed corporal embodiment, psychic fortitude, and sound political awareness inherent to navigating and living life as a woman; she politicizes womanhood beyond the body. Mock clues readers to these distinctions early in the memoir. Reflecting on her “girlhood” growing up in Honolulu, Mock “always” knew early in life that she was a girl. “When I say always knew I was a girl with such certainty, I erase,” she writes, “all the nuances, the work [involved in] the process of self-discovery” (16). The process of self-discovery involved interactions with various communities of women, whom “because nobody was minding us, we minded ourselves,” Mock writes, echoing Toni Morrison’s novel Sula (1973) in the process (135). Learning from these women, these sister-circles of community, instructed Mock on the virtues of womanhood, which throughout the memoir encompasses love, compassion, and care, affective products that emerge from or what she calls the “underground railroad of resources” shared between these women (135). From her best friend—and now make-up artist—Wendi to her preparing dinner with her aunts in Hawaii, Janet Mock cultivates a savvy sense of self while understanding that femininity performs only an expression of womanhood. Women like Kamu, the fist trans woman Mock ever saw, taught her “how to mirror the movements of my ancestors,” (105) she writes, while sex workers, like those who hung on out Merchant street, proved even more critical to her self-awareness and growth. Expanding representations of motherhood and while reflecting on the imperative of kinship formations, Mock writes:

My mother contributed to my sense of womanhood: She taught me tenacity, she taught me that I am my own person, she taught me that I had to do for myself. Admittedly, she didn’t know how to raise a girl like me, but the women on Merchant Street did, because they were me. In the process of the mothers and sisters who walked the path before and alongside me on those streets in down town Honolulu, I uncovered statements that guided me on my path toward womanhood: We are more than our bodies; we all have different relationships to our bodies; our bodies are ours to do what we want with. I stood in awe as these women fought for their womanhood. They taught me, from car to car and date after date, to take ownership of my life and my body (emphasis in the original, 172).

Mock’s entry into the economies of sex work facilitates a personal transition in her life and a narrative shift in the memoir. Prior to her brief stint as a sex worker on Merchant Street—what she calls a “nonevent at the time” (203)—Mock repeatedly understands her sense of self through feminine expression. “Femininity in general,” she writes, “is seen as frivolous. People often say feminine people are doing ‘the most,’ meaning that to don a dress, heels, lipstick, and big hair is artifice, fake, and a distraction. But I knew even as a teenager,” she concludes, “that my femininity was more than just adornments; they were extensions of me, enabling me to express myself and my identity” (147). Mock goes onto to discuss how her body, clothes, and make-up were “on purpose” (147), which, the memoir suggests, constitutes acts of defiance in the name of freedom. With her best friend Wendi at her side constantly, she felt freer to openly express her femininity (110) and as a self-actualized woman living in New York, Mock, “had the freedom to declare who I was…and choose who I wanted to invite into my life,” which was simply “freeing” (247).

Mock’s dialectic between femininity and womanhood might explain her interest in “realness.” I believe that Mock’s interest in realness widens the category of womanhood; realness enables Mock to invest in herstories that widely “mirror the movement of her ancestors.” Reciting the documentary Paris is Burning, and specifically the legendary Dorian Corey and her notion of realness, Mock asserts: “To embody realness, rather than performing and competing realness, enables trans women to enter spaces with a lower risk of being rebutted or questioned, policed or attacked. Realness,” she continues, “is a pathway to survival” (116). Although Mock can “pass” as a cis-gender woman, the beauty of her privilege (and the privilege of her beauty) does not blind her to the violence suffered by trans women of color. Entering into the space of womanhood requires Mock, like her ancestors before her—Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracey (261)—to highlight the violence endured by the less fortunate. As a woman of color, Mock refuses to relish in her ability to pass, and as the numerous narratives breaks sprinkled throughout the memoir suggests, she refuses to wax nostalgia and nausea at the expense of current realities that trans women of color face. For example, when Mock seems to linger obsessively (and excessively) in her past, she interrupts these moments with commentary on the current state of affairs endured by queer youth. These current affairs range from bullying to the lack of resources in schools that could assist educators in creating safe spaces for trans youth. Although Mock’s best friend Wendi helped her cope with and navigate dangerous public spaces, she notes that her friendship with Wendi was “not the typical experience of most trans youth. Many are often the only trans person in a school or community, and most likely, when seeking support, they are,” Mock concludes, “the only trans person in LGBTQ space [and] to make matters worse, these support spaces often only address sexual orientation rather than a young person’s gender identity, despite the all-encompassing acronym,” LGBTQ (118).

Social and economic experiences of trans youth, particularly those of color, persists over time and well into adulthood—a reality that continues to disrupts Mock’s own romance with her past, where for example she shares how she escaped a near dangerous moment after revealing to a young man that she admired that she was born a male. Reflecting on the current debates regarding the politics of disclosure—the exact moment when trans folks should reveal the sex assigned to them at birth—Mock’s formulations suggest that such disclosure is often fraught with danger. She writes: “the violence that trans women face at the hands of heterosexual cis men can go unchecked and uncharted because society blames trans women for the brutality they face. Similar arguments around rape, the argument goes that [by revealing herself] ‘she brought it upon herself’” (161). Having never experienced the degree of violence often faced by trans women today does not exclude Mock from addressing these concerns. She writes: “I recognize that my ability to blend as cis [woman] is one conditional privilege that does not negate that fact that I experience the world as a trans woman no matter how attractive people may think I am (237). Moreover, by the end of the memoir, Mock declares a critical manifesto: “I am aware that identifying with what people see versus what’s authentic, meaning who I actually am, involves,” Mock asserts, “erasure of part of myself, my history, my people, my experiences…I am,” she concludes, “a trans woman of color, and that identity has enabled me to be truer to myself, offering me an anchor from which I can uplift my visible blackness, my often invisible trans womanhood, my little-talked about native Hawaiian heritage, and the many iterations of womanhood they combine” (249).

Mock’s womanhood is an essence shaped, not simply by early trans women like Christen Jorgenson, whom she writes “became the first sex change darling” (255), but one influenced by the lived and imaginative histories of women of color. Writing against cultural media industries that attempt to reduce trans women of color to their genitalia—e.g. Piers Morgan and Katie Couric[2]—explains why Mock devotes a substantial portion of her memoir less on her gender reconstructive surgery (a single chapter), and more on those influential moments that manifests her fierce sense of womanhood; womanhood is political because freedom for all is at stake. Stories like those of Jorgenson, “rarely report on the barriers that make it nearly impossible for trans women, specifically those of color and those from low-income communities, to lead thriving lives. These are tried-and-true transition stories tailored to the cis gaze,” Mock asserts (255). Stories like these, Mock writes, are “best case scenarios” and only reflect a small privileged number of people. Writing against mainstream media narratives centered on trans women, Mock argues that “not all trans people come of age in supportive middle- and upper-middle-class homes, where parents have resources and access to knowledgeable and affordable healthcare that can cover expensive hormone-blocking medications and necessary surgeries” (119). On the contrary Mock’s story is one a “self revelation, mirroring,” she writes, “that of Janie returning home from burying the dead” (240). The social death of trans folks of color gives political meaning to Mock’s life and womanhood.

To reiterate: in Mock’s view, femininity is performative, while womanhood is political in the ways her politics are intersectional and more than not articulate the many oppressions endured by the marginalized and disenfranchised; we may even recall Ann Julia Cooper’s manifesto that without black women, movements toward social progress would remain stagnant. We may suggest further that Mock expands upon Cooper’s thesis and suggests that, in the Age of Obama, it’s not until a trans woman enters “in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole [race] enters with me.”[3]

Women of color writers often carry whole histories of peoples across their backs and while I have not focused on such entangled histories in this review, I would be remiss in my concluding remarks to negate Mock’s attention to these broader, though equally important histories. Histories of colonial violence in Hawaii, the War on Drugs, and among others, the rise of the HIV and AIDS epidemic had devastating impacts in Mock’s own life. Both of her parents fell victim to the crack epidemic, Western linguistic practices have disturbed Hawaii’s otherwise welcoming and diverse sexual and erotic culture, and people of color continue to be the least benefactors of recent knowledge and resources to combat the increasing rates of HIV infection. Mock writes with and through these histories, fully aware that the imaginative space of literary culture cannot completely absolve us of the harsh realities perpetually endured by people of color generally speaking and trans women more specifically. As a woman of color writer, Mock offers one way to confront and deal with pain, transforming (literally and figuratively) how we remember the past, appreciate the written text, and voice our beliefs on love and so much more. Mock has given us a treat that will satisfy our yearnings for years to come. Truly, Mock slays and snatches in the name of liberation realness.

______________________________________

David B. Green Jr. is an effeminate black gay man from the south, black male feminist, and trans-disciplinary Black Studies intellectual. Currently he is a PhD Candidate in the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan and completing a dissertation on Black Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender literary and cultural histories of freedom. He can be reached via email at: dbgreen@umich.edu

David B. Green Jr. is an effeminate black gay man from the south, black male feminist, and trans-disciplinary Black Studies intellectual. Currently he is a PhD Candidate in the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan and completing a dissertation on Black Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender literary and cultural histories of freedom. He can be reached via email at: dbgreen@umich.edu

[1] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality (Vintage Books Edition, 1990), p. 19.

[2] Morgan: http://thinkprogress.org/lgbt/2014/02/05/3250451/piers-morgan-screwed-interview-transgender-advocate-janet-mock/#

Couric: http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/15/living/transgender-identity/

[3] Ann Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South (Oxford University Press, 1988)

1 Comment