Personal is Political: Audre Speaks: Lordean Lessons for a White Man

By Chris Rupertus

The very first thing I say to my seniors on the very first day of the semester is this: “I have a secret about myself I want to share with you.” Then I peek out the classroom door to make sure no one is eavesdropping, adopt a sheepish expression, and lower my voice to a whisper. “I’m a white guy.” The students sitting in front of me, who have boldly chosen to take my 20th Century African-American Literature course over such popular offerings as Literature and Film and Public Speaking chuckle; many of them have taken me before, most of them know that I am the sole teacher of this course, and all of them see as plainly obvious the not-so-secret fact that I am, in fact, a white guy.

I don’t use this opening remark for a cheap laugh, though…well, at least not only for a cheap laugh. Instead, I follow it by asking them a serious question as I pass out the course syllabus: “How can a white guy possibly believe himself to be qualified to teach a course called ‘20th Century African-American Literature?’” Although the all-boys, Jesuit high school where I teach is a predominantly white instutions (PWI), the racial make-up of this course is flipped; the vast majority of students in front of me are black and/or Latino, which is a first for many of them. By initiating our work together with this provocative question, I want to call their attention to what, for them, is an unusual classroom demographic.

And by fielding their honest responses to my question, I hope to shatter any taboos regarding frank discussion of race and class in the course before we ever read or discuss a page of text, listen to a song, or view a clip from a documentary. They always reach the same conclusion to my initial question, which goes something like this: “You’re white, which means you can’t speak personally about the experience of African Americans the way some of us can, but you have studied African American literature, so you’re qualified to teach us about it.”

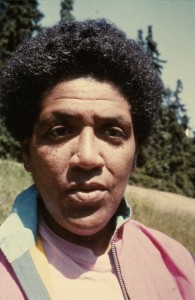

Yet regardless of the focus of my scholarly studies, the simple fact remains that I am a white guy. Not only am I white and male, but I am also heterosexual and Christian. If there were a dictionary definition of the term “societally normative,” my photo could appear alongside it. (If you don’t believe me, take a peek at the headshot that accompanies my thumbnail bio beneath this piece.) Last spring, once I got comfortable enough with my own classmates in Professor Aishah Shahidah Simmons’ inaugural Audre Lorde Seminar I took as part of my graduate English studies at Temple University, I used to jokingly open comments I made in class discussion with the phrase, “As a representative of the patriarchy…” before launching into the substance of what I wanted to say. Using humor to diffuse tense or potentially awkward situations has always been part of my M.O., but of course it really is no joking matter. I actually AM part of the patriarchy; my identities place me firmly in positions of conferred privilege and unearned access to power. So then how can Audre Lorde – black, lesbian, feminist, warrior poet and mother – in short, a person whose identities are as nearly opposite of mine as one could possibly be, how can her words speak to my life, my existence?

I imagine many white men, particularly heterosexual ones, assume the answer to be, really, that she doesn’t. Not to generalize, but people tend to think this way, often unconsciously, right? This person is different from me, so what they have to say does not pertain to me. Historically, white men have been especially adept at making decisions based on this convoluted logic, and the fact that I was the only cisgender, heterosexual white man in a student body of almost 20 in the course serves as likely proof of that. But all of the white men who opted against taking the class during course selection without a second thought missed out. They were mistaken. Because although Audre Lorde may not address/take to task/ask for account of white heterosexual men directly in her work the way she does with white feminist academics, black men, white lesbians, or black heterosexual women, for instance, she speaks to white men. And after reading almost all of Lorde’s published writings, I feel confident in my assessment. Here are some examples of how, culled from my weekly journal entries:

Feb 19, 2013: This past week’s readings from A Burst of Light gave me the chance to speak with my own mom about breast cancer. She turns 61 in April, and while she does not have breast cancer, her own mom did. Mom-Mom was diagnosed when I was in grade school. Her doctors performed a mastectomy on her, and the cancer in fact did recur several years later, metastasizing to her bones, which is what caused her eventual death in 1991 at the age of 64. We talked about how Mom-Mom handled the challenges of the disease, and the only post-operation option offered to her – prosthetic. My mom said she doesn’t remember Mom-Mom even being offered the choice of not getting one. Frankly, this is not a topic that I ever would have thought to discuss with my mom, short of a scenario in which she was diagnosed with breast cancer herself, if not for the readings this week. It gave me a sense of the incredible impact the disease had on my family and, by extension, a greater insight into Audre Lorde’s mind state as she fought the disease.

Feb 12, 2013: In Jennifer Abod’s documentary The Edge of Each Other’s Battles: The Vision of Audre Lorde, one poem that touched me was Sharon Cox’s “two live crew.” Her effort to control her rage while reading the poem aloud was startling and visceral, as she spoke of the denigration and humiliation she felt while hearing misogynistic rap lyrics blaring from boom boxes and car radios – “Suzuki Sidekicks and Jeeps,” specifically. She calls out both NWA and 2 Live Crew as perpetrators of this crime against black woman with strength and authenticity, but what really struck me was that it took me back to an earlier period in my own life. In 1993, my senior year of high school, NWA’s album “Straight Outta Compton” was one of the three cassette tapes that I played over and over in my car stereo. (Another was Tribe Called Quest’s “The Low End Theory,” which is perhaps the greatest rap album of all time; the third was Black Sabbath’s “We Sold Our Souls For Rock and Roll”, and the only thing black about that album was the band’s name.)

Back then, I admired NWA’s willingness to speak truth to power in “F— tha Police” in the face of pervasive police brutality even as my 17-year old self lamented the fact that they blatantly objectified women. Now, twenty years later, Sharon Cox’s raw power and unmitigated excoriation of NWA and 2 Live Crew resonates with me in light of my half-awareness of this as a teenager, but even more so in light of the reading I have done this semester. Sharon Cox stands as the personification of everything Audre Lorde embodied in herself and encouraged in others, namely the willingness to do the challenging and risky work of calling out members of one’s own community who are doing severe harm. The 17-year old me wondered if anyone ever spoke out against the sexist and homophobic sentiments contained in these songs or if fear paralyzed potential critics; the, ahem, 37-year old me knows that as a result, in part, of Audre Lorde’s efforts to empower black women to break their silences, Sharon Cox and people like her did just that.

Jan 29, 2013: In “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” Audre Lorde says that “we rob ourselves of ourselves and each other….for it is not difference that immobilizes us, but silence.”[1] I have come to see this at work in my own life. My family and I live in East Mt. Airy, a community that has families that are like us and families that are constituted much differently than ours. In becoming an active part of this kind of community, I have had the chance to see differences function as bridges rather than barriers – differences of family type, ethnicity, religious affiliation, age, gender, race, and sexual orientation – in the building of a happy neighborhood community. My transracial family is affirmed, as is the family with two moms down the block.

As a result, people are comfortable talking about their experiences, like when I chat with the women down the block about how folks look at my family funny sometimes in grocery store, or ask, “Are all of those kids yours?” as they strain to figure out how we “fit” together. Donna and Laura listen, and although their family make-up is not quite like mine, they can listen empathetically and ally themselves with me. Likewise, when they share how their three kids are asked, “Where is your dad?” or “Which one is your mom?” by new acquaintances, I can do the same. In a small way, they become my sisters; bridges are built between us and the consciousness of each of us is raised. We then become more capable to speak and act against these subtle but damaging offenses when they occur, not just those perpetrated against me or my kids, but also those perpetrated against anyone who appears to others to be “different” in some way.

If Audre Lorde’s words can speak to me, a person whose identities are fundamentally different than hers, then she can speak to anyone’s life. All it requires are two things: (1) the ability to listen, and then (2), the humility necessary to weigh the impact of what one has heard or read, even if it is critical or uncomfortable. True, those two pre-requisites have historically tended to be in short supply amongst those in positions of power, but Lorde’s creativity, strength, and will, three prongs of her genius, command attention, perhaps most especially from people like me, as long as we close our mouths and open our ears.

That mindful attention to her words has enabled me to fundamentally transform my approach to conversations about difference. Last summer, as the George Zimmerman trial for the murder of Trayvon Martin neared its conclusion, I happened to be spending three weeks at Duke University at a seminar on African American Literature and Social History. During a break at one of the sessions, another participant named Paula, an African woman who teaches in North Carolina, approached me.

“Did I hear you say that you have two black sons?”

“Yes, one is seven and one is five,” I offered, thinking that Paula, a mother and grandmother herself, was striking up a friendly conversation about family life.

“How do you think you are ever going to prepare them for survival out there?” she followed.

Shocked, my first inclination was to go on the offensive, roll out the litany of books I had read, documentaries I had watched, intentional life decisions I had made with exactly that question in mind. That is what the pre-Audre me would have done, anyway. But it occurred to me in that moment that what was required here was humility and the ability to listen. All the reading in the world on how to raise black boys paled in comparison to her lived experience, and her tone was not actually accusatory. Instead, it sounded like concern, concern for the well-being of my sons, which, as a father, I needed to appreciate. So I pushed aside my initial indignation, scuttled my snap response, and said sincerely, “I don’t know, Paula. My wife and I worry about that a lot, especially as we follow news of the trial each night. What are the kinds of things you think I need to know to prepare them?” What followed was a rich, honest conversation between the two of us, about how my sons will be targets someday regardless of how they act, and ways in which I can at least begin to prepare them now. She told me about “The Talk,” one about which I had not been fully aware, in which African American adults speak to their boys about how to minimize the likelihood of being targeted. My conversation with Paula equipped me with fresh strategies for effectively parenting across difference, and it was Audre Lorde who prepared me to engage in it.

This kind of new sight can be hard, but it is always good, because it emanates from truth. Once I accept my personal truth – of my identities, of the implicit benefits attached to them, of the ways in which the fact that I benefit automatically means that there are others who suffer, of the ways in which they keep me ignorant of that suffering – I acknowledge my complicity in a patriarchal system. Only then can I begin to actively work against it. What does that mean for me? Professionally, it means that I continually recommit myself to teaching as a political act; Audre Lorde modeled this for me, for all of us in the profession. What texts and authors do I teach? What themes do I foreground in discussion? How do I conduct my classes? Whose opinions and ideas get validated? But it goes beyond my professional life. It needs to influence how I choose to spend money; who I vote for; how I speak to my children, and what I speak to them about; how I interact with my neighbors, colleagues, fellow parishioners, parents, and spouse; what I am willing to stick my neck out for, to speak out against. It ought to permeate my entire existence. Is it a tall order? Definitely. Is it an unattainable ideal? Perhaps. But it is precisely what Audre Lorde wanted, what her revolutionary vision demanded, from all people, regardless of their identities. I believe especially from white guys like me.

_________________________

Chris Rupertus has worked as an English teacher at St. Joseph’s Preparatory School in Philadelphia, PA, for the last 16 years, during which time he has written and taught several new courses, including American Studies, Personal Writing, and 20th Century African American Literature. He is a second-year English PhD student at Temple University, focusing on 20th/21st Century African American Literature.

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire