The Forging of a Caribbean Feminist Consciousness: Laying Claim to Audre Lorde’s Legacy

By Donna Aza Weir-Soley

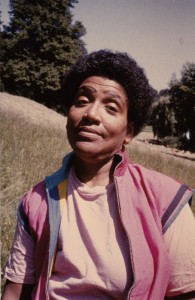

Mothers are central to our identities. Even those of us who do not claim motherhood as central to how we define ourselves as women, know how powerful a presence our mothers are in our lives, sometimes by their presence, and often by their absence. Not all mothers are birth mothers. The women who nurture us spiritually and intellectually can be as important to who we become as the ones who gave birth to us. I am not saying anything new here. What I am doing is an act of naming and claiming one very influential woman who changed my life for good, and for better, Audre Lorde.

I met Audre Lorde when I was a student at Hunter College. She was on sick leave, but would return from time to time to do a reading or launch a book at the poetry center at Hunter College named in her honor. As an active member of the student body, I was first Vice-President and later President of the Audre Lorde Women’s Poetry Center my last two years at Hunter College, where I received my first degree. I was introduced to the ALWPC through Professor Ross Petchesky in my Women’s Studies 101 course. I had written a poem in her class and she thought I could benefit from knowing the women who ran the poetry center. I went to a meeting at the poetry center, poem in hand. As we sat in a circle, introducing ourselves, one of the women asked me what it was like growing up as a lesbian in Jamaica. It must have taken me only a few seconds to respond, but it felt like an eternity because my brain stopped working the minute the question left her mouth. My mouth went dry, and my tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth. My professor had not told me the women at the poetry center were lesbians. I had no idea who Audre Lorde was, although I had been told the center was named after a famous poet. I finally unglued my tongue from the roof of my mouth and managed to answer that, growing up in Jamaica I knew no lesbians and had, in fact, never met a lesbian. The room erupted in laughter. I laughed along, slowly catching up on the joke that was clearly on me.

I remember going back to my dorm room that night and telling George about my encounter. George was my older lover; a US army vet who had spent a good portion of his life in Europe and was quite worldly and sophisticated (to my twenty something sensibilities). Socially conservative but politically progressive, a law student at CUNY, George and I had more in common than not, and I respected his opinion. We talked about the pros and cons of me wanting to join this women’s group to get support for my poetry. I had been writing since I was 11 years old, and had been told I had some talent by various teachers over the years, but had never had anyone take my work seriously, and had never met a published poet. George cautioned me that if I stayed at the Audre Lorde Women’s Poetry Center I would be labeled a lesbian too, and that the stigma of that label would follow me all my life.

The fact that I am here with you today now should tell you that I did not heed George’s advice to stay away from the poetry center. I soon found out that I was not the only woman at the poetry center who did not identify as a lesbian, although the majority of the women there clearly did. However, as Lorde states in “Learning from the Sixties,” “The word lesbian is only threatening to those Black women who are intimidated by their own sexuality or who allow themselves to be defined by it and from outside themselves” (Sister Outsider 144). I had not yet read Lorde’s essay when I had the above conversation with George. But that early act of defiance, that refusal to be limited by the possibility of vicious attacks and gossip, that refusal to judge a group of people I felt were kindred spirits based on their sexual preference or orientation, was one of the best decisions I ever made. For, as Lorde reminded us in Sister Outsider, “…we can put our finger down upon that loathing buried deep within each one of us and see who it encourages us to despise, and we can lessen its potency by the knowledge of our real connectedness, arcing across our differences” (Sister Outsider, 142).

That act of defiance changed my life and has informed almost every major decision I have ever made— from career to motherhood. I joined the Audre Lorde Women’s Poetry Center, signed up for the poetry class that had formerly been taught by Lorde and had been taken over by her protégé Melinda Goodman, and the rest, as they say, is herstory. Some of my closest friendships that have endured for more than two decades (Melinda Goodman, Dorothea Smartt, and Marie-Alice Devieux) were forged at the poetry center. Through my work at the poetry Center I came to know Audre Lorde both personally and professionally. She encouraged me in my writing, told me that I had a strong, unique voice, and advised me to publish my poems. Many of the poems that were published in my poetry collection First Rain (Peepal Tree Press, 2006) were written while I was at the ALWPC.

Similarly, my academic career has been greatly influenced by Audre Lorde’s work and by her mentorship. Audre encouraged me to go to Berkeley to work on my Ph.D. I badly wanted to apply to the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. I was a fellow in the Mellon Minority Undergraduate Program (MMUP) my last two years at Hunter. The goal of the MMUP was to foster intellectual rigor in undergraduate students of color, and to encourage them to pursue doctoral studies as a way of redressing the critical underrepresentation of minority professors in college classrooms across the United States. I was told that I could possibly get a Mellon Graduate Fellowship, but only if I was committed to enrolling in a Ph.D. program. It was not my vision for my life. I wanted to be a poet, and a fiction writer. I did not want to be a college professor or a literary critic. I was young, and I had these had nice little categories carved out for myself. Audre told me to be sensible and to take the money if it was offered, because this was almost a sure thing, Iowa wasn’t. She made a compelling case.

I had been flirting with the idea of applying to Berkeley because of its reputation as an institution that fostered social transformation and political activism, and because it had the number one English department in the nation. Audre cautioned me that graduate school could be a very alienating experience, especially if you were far away from home. She said, “the reputation of the school will not matter if you never graduate from the program. You have to go somewhere where you will find the people who will help you to make it to the finish line.” She told me that if I was going to apply to Berkeley, I should apply because Barbara Christian and June Jordan were there, and they were committed to nurturing the next generation of Black feminists, not because of Berkeley’s reputation. She encouraged me to take a trip out to California to meet June Jordan and Barbara Christian and to check out the school for myself. I took her advice and the end result is that I did get a chance to work with both Barbara Christian and June Jordan and graduated from Berkeley with a Ph.D. in English.

The impact of Lorde’s legacy on my own writing, and on my development as a Caribbean feminist scholar cannot be overstated. In my scholarly book, Eroticism, Spirituality and Resistance in Black Women’s Writings, I discuss the ways in which African spiritual practices such as Yoruba, Voudoun, Condomble and Santeria, allows for the synthesis of the sexual and the spiritual that Lorde discusses in her essay “The Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power.” I analyze the work of two African American women writers (Hurston and Morrison) and two Caribbean women writers (Adisa and Danticat) whose fiction incorporate African spiritual practices in ways that emulate, magnify or reconfigure Lorde’s theories about the uses of the erotic in Black women’s lives.

Similarly, in the anthology I co-edited with Opal Palmer Adisa, Caribbean Erotic, I made a conscious decision to use Lorde’s definition of the erotic when we sent out the call for submissions. In order to avoid a glut of submissions that bordered on the pornographic, we made it clear that we wanted to use Lorde’s model of the erotic as our guide. This resulted in strong selections from writers who made a valiant attempt to honor the erotic as a source of power and agency. The result is a wonderful collection representing diverse, multi-layered perspectives on the erotic from 62 writers (most of them women) from three language areas of the Caribbean– English, French and Spanish.

Lorde’s impact on my personal life, on my choices as a heterosexual woman determined to live with a feminist consciousness that centers self, without being self-centered, centers women and decenters patriarchal privilege, while honoring the men who have played instrumental roles in my life, has come with its own unique set of challenges. When I made the decision to become a single mother while attending graduate school at Berkeley, I knew many single mothers from my Jamaican background, but I knew none who had made the decision to be a single mother knowing she also wanted to obtain a graduate degree and become a university professor, a literary critic and a poet. I quickly grew to realize that Audre’s acceptance (and that of Professors Myrna Bain and Melinda Goodman as well) of my decision was the exception, not the norm.

Audre supported my choice to integrate all the pieces of myself into one whole person, regardless of what anyone else thought about it. It was because of Audre’s example, doing the impossible for a Black woman activist in the 1960’s and 70’s (marrying a white man, then raising two children with a white female lover, all the while carving out a space in which to have her voice heard and remembered for posterity), that I felt authorized to go off to Berkeley with a Mellon Fellowship in one hand, and a little bun in the oven. Audre was one of a handful of people I told that I was pregnant before leaving New York for Berkeley, CA. I told Audre the news while I was visiting her in Lennox Hill hospital in 1991. Although she was the one who was sick, she immediately performed a Caribbean laying on of hands ceremony, right there in the hospital. We commiserated over the fact that the chemo was taking out her beautiful locks; she chanted affirmation for me and the baby, and sent us off to Berkeley with her blessings.

When I got to Berkeley, I pretty much expected that the academic community would treat me like I had some sense. But the sense that I got from some quarters in the academy was that freedom of choice meant freedom to abort, not freedom to choose to do what one knew would be difficult. However, I had already been taught to honor the difficult and sought out kindred spirits I felt would support me and my son while I undertook the mammoth task of raising a baby and completing two graduate degrees.

Although I knew her personally, and benefitted from her mentorship, most of what I learned from Lorde, I did not learn in conversations with her. She was already preoccupied with fighting for her life by the time we met. Most of what I learned from Lorde, I learned from reading her work and observing the choices she had made, both personally and politically. I can truly say that none of the choices I made came without challenges. I can also say, in all honesty, that I have no regrets. I have tried to live as honestly and as authentically as I know how, following a model that had been left for me by the most authentic person I have ever met.

Audre died in November 1992. I am convinced she woke me up as she was passing over. It was 3 am and I still could not go to sleep. My stomach was in turmoil. I don’t remember clearly what was going on that was making me feel so unsettled. I do remember tossing and turning and finally getting out of bed, going straight to my bookshelf, picking up my copy of A Burst of Light. I turned to the autographed title page. Audre had written: “For Donna- A Beautiful Poet-In the hands of Afrekete, Audre Lorde 10/7/90. A Burst of Light was dedicated “To that piece of us that refuses to be silent.” I turned to the essay, “I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities.” I underlined the words:

“It is not necessary for some of your best friends to be Lesbians, although some of them probably are, no doubt. But it is necessary for you to stop oppressing me through false judgment. I do not want you to ignore my identity, nor do I want to make it an insurmountable barrier between our sharing of strengths” (20).

Well! Did this woman ever mince words? I continued reading:

“The terror of Black Lesbians is buried in that deep inner place where we have been taught to fear all difference—to kill it or ignore it. Be assured: Loving women is not a communicable disease.” (21)

I chuckled softly to myself. If there was one thing I had learned being around such powerful women, it was that one had to be true to oneself—not to an ideology. I continued reading:

“Homophobia and heterosexism mean you allow yourselves to be robbed of the sisterhood and strength of Black Lesbian women because you are afraid of being called a Lesbian yourself. Yet we share so many concerns as Black Women, so much work to be done. The urgency of the destruction of Black children and the theft of young Black minds are joint urgencies. Black children shot down or doped up on the streets of our cities are priorities for all of us. The fact of Black women’s blood flowing with grim regularity in the streets and living rooms of Black communities is not a Black lesbian rumor. It is a sad statistical truth.” (24)

Suddenly the room was still. A drop of water fell on the book and I realized my eyes were crying. Was that my ears ringing? It was the phone. It was Melinda Goodman calling to say that Audre had just transitioned. I had to wait for a decent hour to call Barbara Christian, Valorie Thomas, Claudia May, Opal Palmer Adisa and Daphne Lamothe. Together we organized a memorial service for Audre in the English Department. I laid a beautiful altar and we read from her work. We celebrated her life and her legacy. I promised her that I would act like I was raised right, by a good feminist mother, arguably, one of the best. Most days I keep my promise.

Hardly a week goes by that I do not have occasion to think about or talk about Audre Lorde. When I betray my own feminist principles, I am always reminded that I was not “raised” that way. My students are a constant reminder of how important it is to practice what you preach. They assume that competition between women is the natural order and that any other model renders you naïve and vulnerable to attack and annihilation. Our job is not done, sisters. It is up to us to teach them that SIS stands for Sisterhood is Solidarity, instead of Shame, Isolate and Shun. As bell hooks points out, the media has done an incredible job of distorting the feminist movement and changing the conversation from patriarchal domination and sexism to a power grab between the sexes. My students honestly believe that sexism is about women wanting to dominate men and, as a result, they do not want to identify with the label. They have no clue that birth control, abortion, and so many other gains they take for granted, were won by this movement. As someone who sat at Audre’s feet, however briefly, I have a responsibility to make sure that her words reach the ones who are too young to have had that experience. I take that mission seriously. Because it is not about me. For me, poetry is not a luxury, and neither is teaching and reaching out to this generation who still need warriors and poets who act boldly, whether we are afraid or not. For as my mother-sister said: “Poetry is not only dream and vision; it is the skeleton architecture of our lives. It lays the foundation for a future of change, a bridge across our fears of what has never been before” (Sister Outsider, 38).

So if I channel Audre Lorde in my work, it is not because I have nothing original to say for myself. I have been on my own since I was 11 years old because my mother had to surrender me to other people who could afford to send me to school. Truly, I was not meant to survive. Most of what I went though, growing up in Jamaica after my grandmother died, should have destroyed me. But it didn’t. I have been through so much in this life that If I never write anything but autobiography again, I will still have too much to say and not enough time in which to say it.

Lorde’s boldness, her absolute refusal to allow her fear to get in the way of her purpose, her generosity to the fledgling poet that I was when I met her (and to so many more just like me), and most of all, her integrity, her steadfast refusal to “leave” her pen “lying/in somebody else’s blood,” her insistence on loving her sisters fiercely even when she had to speak harsh truths to them, make her the most remarkable woman I have ever met, and still the most necessary leader and teacher Black Feminists have in our continued struggle to be fully and completely whole. Because she did not just look outside of herself, did not just examine others to seek out their flaws and shortcomings, but turned the light on herself, and acknowledged her own anger, and tried to figure out how she could make it useful rather than deny its existence, she earned my respect. Because she did not pretend that she alone had it together, while the rest of us were floundering, but even examined her own limitations in trying to raise a Man-child in an all female household, I am still learning from her how to parent (and how not to parent) my sons, in this new phase of my life. I can only hope that I will continue to work towards being as bold, and as loving, and as fierce as Audre and the other women at Hunter College “raised” me to be. For indeed, as a poet, and a critic and a teacher, and a mother, and a sister, and a friend, I am proud to be derived from Audre, and before her my grandmother Theresa Matilda, and before her Nanny of the Maroons and Harriet Tubman, and before them Yaa Asantewaa, and before her, Afrekete, and before her, MawuLisa.

________________________________________________________________

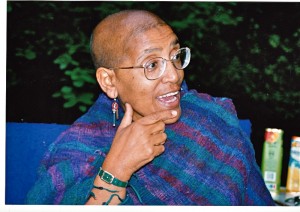

Dr. Donna Aza Weir-Soley (known to her friends as Aza) was born in St. Catherine, Jamaica and migrated to the United States at the age of 17. She attended St. Mary’s College and St. Elizabeth Technical High School in Jamaica, but received her diploma from Andrew Jackson High School in Queens, New York. She then attended the State University of New York at SUNY, Cortland for a year. Weir-Soley graduated summa cum laude in English/Special Honors Curriculum from the City University of New York, Hunter College. Dr. Weir-Soley received her MA and Ph.D. in English from the University of California, Berkeley. She is currently an Associate Professor of English, African/African Diaspora Studies and Women’s Studies at Florida International University. Dr. Weir-Soley is both a Mellon and a Woodrow Wilson Fellow. She is the author of a poetry collection, First Rain (Peepal Tree Press, 2006), a scholarly text, Eroticism, Spirituality and Resistance in Black Women’s Writings (University Press of Florida, 2009), and co-editor (with Opal Palmer Adisa) of Caribbean Erotic (Peepal Tree Press, 2010), an anthology of poetry, fiction and essays which includes the work of 62 writers from the English-speaking, Spanish-speaking and French-speaking Caribbean.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Works Cited:

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider. New York: The Crossing Press, 1984.

——–Our Dead Behind Us. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986.

——–A Burst of Light. New York: Firebrand Books, 1988.

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire