What Ralph Ellison Can Teach Us about Trayvon Martin

In light of the recent decision by the school board of education in Randolph County, North Carolina, to ban Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man from their libraries—partly because of a parent’s complaint that the book is not age-appropriate material for teenagers and partly because one board member claimed he could not “find any literary value” in the text—I cannot help but reflect on a few of the key lessons I’ve learned from the novel, particularly as I attempt to cope with the verdict in the Zimmerman trial.

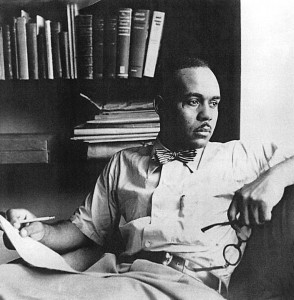

I do not share these lessons as a defense of Ralph Ellison: a Black author who has won the National Book Award in fiction has already earned his place in the pantheon of American letters. But rather I share them as a way to uncover what the novel can teach us about American race relations in general and about the perception of Trayvon Martin in particular.

As a professor of English, I am wont to use literature to make sense of the world, so, in the aftermath of the Zimmerman verdict, Ellison’s novel was essential reading. I returned to Invisible Man not only to understand what might have been in Zimmerman’s mind as he identified, pursued, shot, and killed Trayvon Martin on that rainy night in Sanford, Florida, but also to come to grips with the particular challenge facing the all-female jury who, in the absence of Trayvon Martin’s version of events, relied on the evidence presented at trial as well as their imaginations to fill in the gaps of Zimmerman’s story.

Ellison’s book was especially helpful after I watched Anderson Cooper’s interview with juror B-37, a middle-aged white resident of Seminole County and mother of two. Despite claiming that Zimmerman likely fabricated and embellished portions of his story and despite conceding that there were details about that night that no one could ever know, she essentially believed in “George” (as she affectionately called him). And it is this—her firm, abiding certainty about the goodness and rightness of George, not Trayvon—that most struck me as I watched her interview with Cooper then and that remains foremost on my mind two months later as news of Zimmerman’s subsequent violent behavior appears in the headlines now.

Her empathy and compassion for Zimmerman were offered with such aplomb that it forced me to wonder, How could she be so certain about Zimmerman’s fear, his “good heart,” and his eagerness “to help people” and yet remain so uncertain about Trayvon’s fear and innocence—unless she was unable to see Trayvon in the first place?

Let me explain.

One reason for juror B-37’s attachment to George Zimmerman and her detachment from Trayvon Martin has to do with the concept of invisibility, which Ralph Ellison examines in his 1952 novel Invisible Man. In the book, Ellison’s protagonist clarifies what it means for a Black man to be invisible in America. He states in the opening paragraphs of the novel’s “Prologue,”

I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. . . . That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact.

Ellison’s protagonist carefully points out that he is not actually invisible, but rather he is misrecognized; that is, people refuse to see him accurately. The problem lies within the spectator’s eyes. These eyes can cause serious vision trouble, producing blurriness instead of clarity and providing only a partial, biased view of events instead of a full, unobstructed one. At best, they are unreliable and untrustworthy; at worst, stifling and oppressive.

Yet, as I watched juror B-37’s interview, I realized that these were the eyes she looked through as she saw the images of and heard testimony about Trayvon Martin during the trial. It is why she had trouble imagining his fear and intimidation as Zimmerman pursued him. It is why she could not hear Trayvon’s voice screaming for help on the 911 call. And it is ultimately why she could not see Trayvon’s good heart. With respect to Trayvon, unlike with respect to George, this juror’s capacity to feel fell by the wayside as she seemed to suffer from a form of sensory ineptitude and willful critical blindness. Trayvon was more of a perpetrator than a victim for her. Because she, similarly to Zimmerman, refused to see Trayvon, all she saw was a distortion.

Trayvon’s invisibility is as sure a sign as any that misrecognition is a dangerous thing. It harms, it injures, it shames, it belittles, and it kills. It allows the observer to see things that are simply not there, while seemingly absolving him or her of any culpability for the unreal things they claim to see. To be Black in America is to live with the glaring stare of misrecognition: we feel it in the workplace; we sense it in the classroom; we bump up against it on the street; we anticipate it at the store; we encounter it in our community and neighborhood; and, whenever and wherever it rears its ugly head, we confront it with as much strength and courage as we can muster.

The power of Ellison’s novel lies in its ability to describe this strange yet familiar sensation of vitriol and contempt, to articulate this feeling of suspicion and disregard that is often difficult to decipher, and to affirm that the problem rests with the seer, not with the person being seen. Reading a book like this is a kind of conversion: once you’re finished, you will not look at the world in the same way.

Rather than hide from the Zimmermans of the world or acquiesce to one jury member’s perspective, many people are refusing to remain silent. What’s promising about the responses of all who are protesting, rallying, teaching, writing, and talking about Trayvon is the insistence on ensuring that Trayvon is seen, not as a criminal, threat, or danger, but as a child, a friend, and a brother deserving of respect and worthy of protection. What’s also promising is the recognition that a fight for justice on behalf of Trayvon is a fight for justice for people of color, for the disabled, for the poor, for women, for youth, for LGBTQI communities, and for immigrants—who all experience various forms of invisibility in the United States. The Randolph County School Board in North Carolina may have failed to comprehend the far-reaching implications of Ralph Ellison’s novel, but we should not. We have an opportunity to use Trayvon’s story to save our own lives. Let’s continue to heed the call.

________________________________________________

Pingback: What Ralph Ellison Can Teach Us about Trayvon Martin – The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire | [Modern Times]