An Open Letter to Amanda Marcotte

By Tara L. Conley

Dear Amanda.

Resting uneasily in this contentious, but necessary space, I write this letter to you. Gloria Anzaldúa calls it a nepantla space of consciousness, one of which is characterized by discomfort; a ‘psychic and emotional borderland,’ a threshold space where transformation can occur. I also offer this letter with feminist activist and online organizer Brownfemipower’s work and legacy in mind. In the spirit of nepantla and in homage to the work of feminists who came before us, I hope by the end of this letter we both find ourselves excruciatingly uncomfortable.

I’m somewhat familiar with your work. Admittedly, however, I’m more familiar with the controversy surrounding your prior work. I remember first hearing about you back in 2008, when you were accused of appropriating the ideas of Brownfemipower (Internet pen name), a woman of color activist and blogger who wrote and spoke openly at a WAM (Women, Action and the Media) conference about immigration-related gender violence within her community. It was during this conference that Brownfemipower publicly decried rampant sexism and racism that immigrant women in the U.S face.

Soon after Brownfemipower’s WAM speech, you published an article about the link between sexualized violence and dehumanizing terminology, like “illegal alien.” Your main points, according to some, resembled Brownfemipower’s speech and online writings about gender violence in immigrant communities. Brownfemipower’s stance on immigration-related gender violence was well known by the online feminist community long before the WAM conference. Yet her work, and the work of notable people of color who were already writing about the topic, was not credited or even referenced in your article that subsequently went viral. As tensions increased, Brownfemipower chose to stop blogging about pro-immigration issues altogether. Though some felt she gave up, Brownfemipower asserted otherwise, “I am not giving up. I am just thinking. And resting. And reading my beloved books and soaking my tired dogs.”

Though you adamantly denied stealing ideas from Brownfemipower, many feminists were angered by what they believe to be an all too familiar case of a white feminist appropriating the ideas of a woman of color. This, coupled with the fact that you had recently published your first book with Seal Press, which featured on its cover a blond white women dressed in animal print holding a spear in the jungle, called into question your privilege and the overall meaning of inclusive feminism in the 21st century.

On February 12, 2013, I randomly stumbled upon your tweet in response to the #TellAFeministThankYou hashtag, started by Melissa McEwan (@Shakestweetz) as a way to call out and bring attention to feminists who are often personally attacked online.

I presume your tweet was meant simply as a way to celebrate the work of fellow feminist bloggers and friends who, in their own right, have contributed to the burgeoning phenomenon that is online feminism.

But perhaps most pausing about your tweet, Amanda, was the way in which you credit certain feminists with whom you best align. When you cited these women, your friends, as foremothers who essentially created online feminism, you implicitly erased a noteworthy and rich history of feminists who were doing other kinds of work online.

Your tweet, Amanda, was shortsighted and problematic.

Perhaps you should have considered the medium through which you chose to express your admiration and interpretation of online feminism. Surely you must realize that your Twitter stream, which reaches over 20,000 people, comes with certain privileges, and I’d argue responsibilities that few feminists and activists enjoy. When you tweet a response to a trending feminist topic, people notice. Nonetheless your tweet called attention to long-standing issues of exclusivity and erasure that many people experience within past and present feminist movements.

With that said, allow me to highlight the work of other feminists who were engaging, and subsequently creating, what you now seem to understand as online feminism.

I’ve written previously about the virtual volunteerism work women were doing immediately after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Online organizers like Lesley Holly, creator of the blog Real People Relief, was engaged in online feminism by using mediated spaces to write about relief efforts and connecting women and their families to resources across the country. Lesley writes,

I am a problem solver, a researcher and a networker. I am also disabled. 5 years ago, I was fighting chronic sinusitis, awaiting surgery, when a virus attacked the nerves in my right ear. Daily life is a challenge. I’ve improved so much, but am still so far from being able to work again. It’s frustrating beyond words. However, even if I can’t recover, that doesn’t mean others shouldn’t be able to. So ever since The Storm of ’05, I have worked every day at finding ways to help both individuals and volunteers get the help they need to speed the recovery efforts. I may not be able to come down and get my hands dirty, but I can make it so more people can. I am now focusing my attention on the individuals who have fallen through the cracks of ‘organized relief.’

I was fortunate to have had brief correspondence with Lesley during this time. She provided me with insight into other ways women and feminists were working on behalf of their communities through online volunteer work. This, I thought, was part of what online feminism is about: selfless and tireless service. Lesley Holly, although widely unknown as an online feminist organizer, was in fact paramount to the early online feminist movement. But Lesley is just one example of many other feminists who were organizing and speaking out. I’ll be the first to admit that I, too, am unaware of countless other nameless and faceless feminists–cis women, cis men, trans, people of color, able-bodied, and otherwise–who were blogging, organizing, and distributing multimedia content before 2005 on spaces like Livejournal and Blogger (both first established in 1999), and on Myspace (first established in 2003).

As I present to you this truncated history of feminist practices within electronically mediated contexts, Amanda, I wonder: What is your understanding of online feminism?

When I think of online feminism, I think about the work that women virtual volunteers were engaging in during 2005 after Hurricane Katrina. I also think about the work Brownfemipower was doing online and offline to advance social justice for immigrant women. These women were doing feminism long before the hashtag functioned to archive trending topics. My understanding of online feminism is not limited to creating blog posts that end up being cited on cable news programs, nor is my understanding of online feminism limited to the ability of one to register a domain name. While the written work of feminists online is certainly significant, as well as the video, audio, and social media work feminists engage in daily, to me these modes of production are merely a piece of what makes up online feminism.

Fundamental to my understanding of online feminism is the notion that service to our communities, often mundane and unnoticed at first, are mediated by sustainable practices of organizing and production that can lead to political action and critical connection offline. But perhaps even my own view of online feminism is skewed. I readily admit that I came to know online feminism based on the work feminists were doing on the web as a result of natural disasters and (inter)national protests, as we saw with cyberactivists of the Arab Spring and with what we saw in 2007, when young college students of color across the United States came out in protest during the Jena Six controversy.

Perhaps it’s presumptuous of me to assume you weren’t aware of our histories of online feminism. Perhaps I, too, present a shortsighted view. But when I come across a tweet like yours, Amanda, I can’t help but question your positionality.

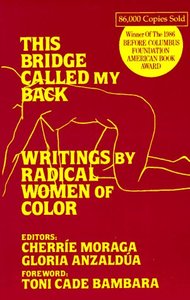

I’m reminded of the work of feminist authors that appeared in This Bridge Called My Back. The anthology illustrated the struggles women of color writers faced when up against a feminist movement that was largely white, middle-class, heterosexual, and able-bodied. It was not so much that the movement collectively mirrored hegemonic social identity categories at the time, it was that the voices within the movement, its leaders and well-known representatives, primarily consisted of white, middle-class, heterosexual, and/or able-bodied cis-gendered women, usually with book deals.

I’m reminded of the work of feminist authors that appeared in This Bridge Called My Back. The anthology illustrated the struggles women of color writers faced when up against a feminist movement that was largely white, middle-class, heterosexual, and able-bodied. It was not so much that the movement collectively mirrored hegemonic social identity categories at the time, it was that the voices within the movement, its leaders and well-known representatives, primarily consisted of white, middle-class, heterosexual, and/or able-bodied cis-gendered women, usually with book deals.

I imagine that what I witnessed online in 2008 with Brownfemipower was similar to what many women of color feminists witnessed and felt during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when there were no blogs. When Audre Lorde wrote an open letter to Mary Daly in 1979, she acknowledged Daly’s intentions while also calling out Daly’s dismissal of Black women’s experiences in Gyn/Ecology (1990).

Lorde asked of Daly: “Have you read my work, and the work of other black women, for what it could give you? Or did you hunt through only to find words that would legitimize your chapter on African genital mutilation in the eyes of other black women?”

Lorde was addressing in print what feminist activists, who are often erased within the online feminist movement, continue to confront presently.

Though Lorde’s exchange with Daly differs contextually from the controversy surrounding the alleged appropriation of Brownfemipower ideas and from the controversy surrounding your tweet, the underlying issue concerning these controversies essentially has to do with the ways in which your privilege as a feminist with a platform implicitly asserts ownership of online feminism. As we have witnessed throughout the generations, the problem with this sort of naïveté is that it ends up deflecting our attention from important issues like preserving the stories and centering the perspectives of women and feminists without such a platform, but who also love and work despite confronting inequalities, both online and offline.

Amanda, we are more than any well-intentioned hashtag could ever embody. In addition to the women you cited in your tweet, there are others of whom you should be aware. These feminists have been able to spread advocacy projects across time and space, and organize bodies to protests in cities and neighborhoods across the globe. They have brought together domestic and international allies in our fights for justice and relief. They have called out others and, at times, they’ve had to confront themselves. They have moved advocacy work beyond stationary online and offline spaces. As a result, these feminists have contributed to third space consciousness where they fight as much for the preservation of themselves as they fight for the preservation of others. This movement toward consciousness—born of techno advocacy practices that span computer mediated and non-computer mediated contexts–is a threshold where we can see ourselves through the eyes of others and by way of panoramic views.

I hope, as you have reached the end of this open letter, that you not only see but also notice the work of feminists who have come before us.

____________________________________________

Tara L. Conley is founder of MEDIA MAKE CHANGE and current doctoral student at Teachers College, Columbia University. She writes about digital media justice and Internet technologies in the lives of women, people of color, and youth. Her current research focuses on mobile advocacy initiatives for court-involved youth in New York City. You can follow her on Twitter @taralconley

Tara L. Conley is founder of MEDIA MAKE CHANGE and current doctoral student at Teachers College, Columbia University. She writes about digital media justice and Internet technologies in the lives of women, people of color, and youth. Her current research focuses on mobile advocacy initiatives for court-involved youth in New York City. You can follow her on Twitter @taralconley

24 Comments