EMERGING FEMINISMS, Why Were We Laughing at Drake’s Dancing in “Hotline Bling?”: On Body Movement and Black Masculinity

By Lauren M. Todd

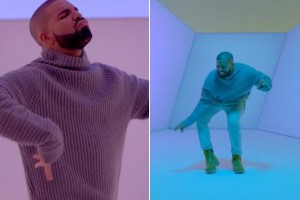

In the past month, there has been a huge buzz of unabashed laughter at the Grammy-Award winner, Billboard Chart record breaker, Drake, in his music video for his newest single, Hotline Bling. I admit that I, too, watched the video, laughed, and initially had the same questions as many others:

Why is he doing this awkward, interpretative dance;

Why is he wearing this ugly sweater while doing so; and

What was he thinking?

I also admit to spending a decent (and unproductive) amount of time watching several skits and parodies of the video, where Drake was placed alongside Carlton from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, in the theme song to The Cosby Show, as a character in Wii Tennis, as a commercial actor for a late night pizza parlor, and many other absurd scenarios that only heightened the momentary hilariousness of Drake’s video.

Sometime later, I sat down to watch the newest episode of American Horror Story starring Lady Gaga. Her character, a sort of vampire with an eerie creepiness mixed with soft seductiveness, reminded me of her history of eccentric music videos. I rewatched the video for Bad Romance and noted her creepy and often awkward dance moves—and then, I thought back to Drake.

Obviously creepy, awkward, eccentric music and accompanying videos are a part of Lady Gaga’s artistic aesthetic, however, there is a particular way in which popular music consumers accept White women moving their bodies in a way they don’t like, or allow, Black men to do. They will watch countless videos of Lady Gaga, Miley Cyrus, Madonna, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, and many other White women artists extending the limitations of normative dance routines, dancing dorkily in their bedroom windows and at parties, and embracing that boundary-breaking body movement. Sometimes, they will even embrace that behavior as uplifting and affirmative. Folks are also accepting of White men, like Macklemore, dancing and dressing in what would normally be considered socially awkward ways. These same people, however, do not extend this option to Drake. Popular music consumers are uncomfortable with Drake renegotiating and performing new understandings and embodiments of Black masculinity; they will not let him do so without making a mockery of him.

The reason why I initially laughed at Drake—and the reason many others laughed, too—is because he is a Black man who makes very good, very popular hip hop music, who is doing something we rarely see his body do. I stopped laughing because he is doing something that doesn’t fit our understanding of Black men rappers. Because he is doing something men like Jaden Smith and Pharrell Williams might do and be understood differently. Drake, because of what he looks like, who he is, and what he raps and sings about, cannot be a “carefree Black boy” expressing himself through mostly solo, uncoordinated, seemingly misplaced dancing. Popular music consumers will not have it; they will (as they have done) tear it to shreds, laugh it off, and hope it goes away in the morning. They misunderstand and misconstrue the important work Drake is doing by dancing in the Hotline Bling video, which might help in making more bodies and types of body movement acceptable.

So please, don’t expect Drake to dance as he did in Hotline Bling ever again (unless as a profit-making tactic or as a way to flip the joke on its head).

This is not to excuse or overshadow Drake’s misogynistic lyrics, even those in Hotline Bling, and I am not claiming myself to be a hip hop scholar; rather, I am reflecting deeply on this divide within music video production and performance because it is emblematic of an even deeper issue:

the freedoms specific bodies have, or are denied, in terms of movement.

The bodies of White artists (that are often read as cisgender, straight, young, and able), both in music videos and in the U.S. specifically, are provided with and can embody particular freedoms that are denied to Black artists, especially Black men in hip hop. Because Black men exist in a world that is racist, violent, and monitoring their every move, their masculinities are so severely regulated that even something like dancing in a music video is up for intense scrutiny, subjugation, and suppression. Therefore, Drake’s awkward dance moves are metaphors for what the white supremacist state refuses: Black bodies being free.

Black bodies being free—to travel in the ways that they do, to dress in the ways that they like, to speak in the ways that they want, to dance in the ways that they feel—is a set of freedoms that should not, cannot, and will no longer be denied. Drake’s dancing in Hotline Bling is just one important moment in a history of radical body movement and it is not funny; it’s revolutionary.

***********

Lauren Todd is a queer feminist activist from the New Haven, CT area. She is earning her Master’s in Women’s Studies at Southern Connecticut State University, while working in Student Affairs as the graduate intern for the LGBTQIA+ Center. Her master’s thesis is titled “Loving Interracially: Queer Manifestations, Representations, and Narratives of (In)Visibility.” She loves to practice self-care by sleeping long, eating good, and laughing hard.

Lauren Todd is a queer feminist activist from the New Haven, CT area. She is earning her Master’s in Women’s Studies at Southern Connecticut State University, while working in Student Affairs as the graduate intern for the LGBTQIA+ Center. Her master’s thesis is titled “Loving Interracially: Queer Manifestations, Representations, and Narratives of (In)Visibility.” She loves to practice self-care by sleeping long, eating good, and laughing hard.

4 Comments