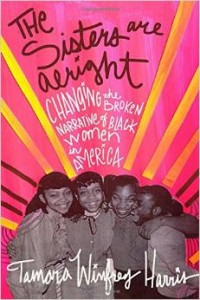

Feminists We Love: Tamara Winfrey Harris

Tamara Winfrey Harris is a writer who specializes in the intersection of race and gender with current events, politics and pop culture. Her work has appeared in The Chicago Sun-Times, In These Times, Ms. and Bitch magazines and online at Fusion, The American Prospect, Salon, The Guardian, Newsweek/Daily Beast, Jane Pratt’s XO Jane, The Huffington Post, Psychology Today, Change.org and Clutch magazine. She has been called to address women’s issues in major media outlets, such as NPR’s “Weekend Edition.” Her first book, The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America will be released on July 7 by Berrett-Koehler Publishers. For more, visit www.tamarawinfreyharris.com,twitter.com/whattamisaid or Facebook.com/TamaraWinfreyHarris.

You have developed a significant and fiercely independent body of work on the intersection of gender justice, black women’s self-determination and liberation. What were your early personal, literary and political influences?

I would count my mother as my earliest influence of what black feminist womanhood looks like. (Even though I didn’t know she considered herself a feminist until a few years ago.) Aside from a few courses, I came to the foundational literature of feminism relatively late—post-college. Three books were life-changing for me: bell hooks’ Ain’t I Woman?, Joan Morgan’s When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost and Lisa Jones’ Bulletproof Diva. But more than anything else, the black feminist internet has played a tremendous role in shaping my views on gender and specifically the liberation of black women. It was the feminism I found in places like The Feminist Wire, Crunk Feminist Collective and Racialicious, that connected the ideology of the feminist academy to my everyday experience and helped me understand the importance, actually, imperative, of being a loud and proud black feminist. It was my experience in those places that led me to reread iconic feminist works and discover pioneers like the Combahee River Collective. I suspect my experience isn’t unique.

What motivated you to write your forthcoming book evaluating the politics of black women’s subjectivity?

My original idea was to tackle the incredibly sexist and racist messaging of the so-called “black marriage crisis” and the associated headlines and help-the-sisters-get-hitched literature. But I realized that our problem is bigger than Steve Harvey’s oeuvre. The way our society views black women is fundamentally broken. And, yes, how our marriageability is discussed is one reflection of that brokenness, but so is the way the media talks about black women’s health and the way social media talks about Nikki Minaj’s ass. The conversation is flawed and relentlessly negative. So, my focus expanded. My goal was to interrogate the biases that inform how society sees black women, but also to present a more complicated, authentic and hopeful view of what it means to be a black woman today.

What impact do you hope the book has on public perceptions and/or public policy?

One of the women I interviewed for the book shared this amazing analogy. She says, “I am fat. When I walk into, say, a Banana Republic . . . well, I see those clothes, but I know that store is not about me. When I see those stories on the news about black women and marriage? Well, that’s not about me either.” Existing as a black woman in America is like living in a fun house. You are constantly confronted with warped images of yourself. You know your truth, but it is stretched and distorted into something else. I am tired of seeing analyses of black women that are not about us or, worse, uncharitable or actively hostile to us.

I think authentic stories are an antidote to anti-black woman propaganda, but, ultimately, I don’t know if this book is about changing what other people think about black women. I wanted to write something that offered black women a representation of our lives, without the distortion. (Though I don’t pretend that the women in the book are representative of all black women.) We don’t get enough credit for being authorities of our own lives, you know?

Your book has a laser focus on the damned-if-we-do-damned-if-we-don’t paradoxes of black women’s sexuality. What has (and hasn’t) changed for black women who struggle to self-determine and self-direct around issues of sexuality and gender identity in the “brave new world” of heightened social media visibility?

As long as society thinks sexual desire is for men, sexually liberated women are going to catch hell. It is especially hard for black women to push back against this idea, because of the stereotype that we are naturally lascivious. For us to claim the word “slut” like many white third wave feminists have, can feel like embracing a stereotype that has burdened us for centuries. But then, the rectitude demanded by respectability politics can feel like a straight-jacket, too. What I heard from the black women I spoke to is that it is often hard to figure out where our own sexual desires lie beyond what society expects from us—especially in a 21st-century America that loves overt sexually, but remains Puritanical and patriarchal. Are we shaking it fast for ourselves or the male gaze? Are we celibate for our peace of mind or the patriarchy? Can a queer sister get some love up in all this heteronormativity?

Societal views about women and sex are complicated and will remain so for the foreseeable future. I think for black women—for all women—the best thing we can do is discover what works best for us physically and emotionally and honor that.

With its insightful blend of personal narrative, cultural critique and reflective interview, your book follows in the critical and literary footsteps of such feminist/womanist writers as Michele Wallace, Patricia Hill Collins and bell hooks. Similar to these authors, you unpack the often damaging effect the myth of the self-sacrificing black superwoman has on black women’s mental health and wellness. How do you see these themes playing out in the lives of black girls?

There is a cultural resilience that is our birthright. And it is inspiring. But we have to teach young women and girls that their needs and desires are important. And we have to teach them that they don’t have to bear everything without complaint. And we have to tell them that it is okay to say “no” when they want to. And we have to let them know that nobody is strong all the damn time. And that’s okay. That probably sounds unremarkable. I mean, of course, no one is strong all the time. But the strong black woman myth is killing us—literally. Several of the women I spoke to told harrowing tales of friends and family who were too busy carrying the load for everyone else to take care of their own well-being until it was too late. I think, particularly within our own communities, black women’s value is measured against how much we can bear and how hard we sacrifice for everyone around us. One interviewee I spoke with reckoned that we begin learning self-sacrifice early, as girls. We are groomed to be the mules of the world. And then later people will wonder at our unchecked depression and high rates of diseases that may be managed by self-care.

Waiting to shed the idea of superhuman strength in middle-age may be too late. We need to make sure black girls never absorb the idea that they are unbreakable, because they are not. Human beings are not.

Many young African American women and other women of color (Millennials and younger) don’t relate to feminism, see it as “white” thing, believe it is a relic of bygone era, etc. Do you believe feminism is culturally and politically relevant for young women of color and if so how can the disconnect be addressed?

And as I explain in my book, many of the issues plaguing black women are related to systemic racism and sexism. Of course feminism is relevant when black women face high rates of domestic homicidal violence and poverty and rape. But, you know, for a while, during the 2008 Presidential Election, I might have agreed with some of those women rejecting the label “feminist.” I was so dismayed about the way some mainstream feminists were ignoring the lived realities of black women to build a case for Hillary Clinton that I was ready to give up the feminist label. But then I remembered all the brilliant black feminists who put their lives into fighting for women’s equality and I decided that ceding a movement that my foremothers helped build doesn’t make sense to me. Part of making young black women understand that feminism is for them, too, is making sure they know about black feminists, past and present, who speak to their issues. But I also think that the Internet and pop culture both play a role in making feminist thought accessible to a new generation outside of the academy. It means something when the biggest pop diva in the world stands on stage in front of millions and proclaims herself a feminist. Imperfect though her feminism may be (And whose isn’t?), Beyonce will bring more women to feminism than I ever will.

0 comments