No Doubt: Your Mission, if You Choose to Accept it, is to Make Revolution Irresistible

By Guest Contributor on November 24, 2014By Nadine Patterson

When Toni Cade re-told the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, the tale of a blonde-haired blue-eyed child who broke into the Bears family home, vandalized the place, and stole their food, she re-visions the world from a Black & Brown, non-white supremacist perspective. The simple tale became a political hand-grenade.

Either a story supports white racist patriarchy or it does not. Even a simple children’s tale tells us who to fear, who is good, who is smart, who is beautiful, who is human. The brown cuddly bears in the original story have no rights to property or privacy. The young white child has the right to steal and invade because she is human, and not a “beast.” The images that we create do matter. The stories we tell have impact. As Toni Cade once said,

Cultural workers are mental health workers.

“Hollyweird” (Toni Cade’s description of Hollywood) perpetuates stereotypes in order to support the white supremacist structure. If “Hollyweird” were truly interested in making as much money as possible, they would create a wider variety of narratives that privileged people of color and women as protagonists, romantic leads, and saviors of the planet. In terms of sheer numbers, we are the largest audience out there.

********************

Philadelphia in the 1990s was a cultural haven. All three of my literary guiding lights—Ntozake Shange, Sonia Sanchez, and Toni Cade Bambara—lived here. Their reach was global, but Sister Sonia and Sister Toni Cade worked locally as well. Sister Sonia nurtured two generations of poets, writers, playwrights and musicians (yes, musicians) through her classes at Temple University. I first met Toni Cade as a student in her screenwriting class at Scribe Video Center in 1989. Toni Cade Bambara held court on Kater Street, and inspired a generation of filmmakers to be cultural workers. Her classes in screenwriting were also classes in world cinema, Black British cinema, women’s cinema, ancient mythology, political science, world economics, African American literature, documentary filmmaking, aesthetics, and activism.

Her knowledge was all-encompassing. And then she would break it down. Paraphrasing Toni:

Everyone in Western culture dreams in five parts. There are other ways of telling stories, but this is how we dream. Use it. Record your dreams from the last image before you wake up and trace your dream backwards. What images and sounds remain with you are the ones that are the most powerful. Use them.

That was the best advice I ever received in terms of screenwriting, after four years of college and 1.5 years of grad school.

********************

Black people will save America from itself and in the process help to save the world. We live in the belly of the beast for a reason,

counseled Toni Cade Bambara. The impact of African American culture globally is truly astounding. Our music has transformed the world stage in terms of history, economics, and politics. Our freedom struggle has been emulated around the globe in large part because of our music. Imagine if we created a cinema that was truly expressive of our spirit, the way our music is. What would the impact of that be? How would those narratives transform our perception of human history and civil society?

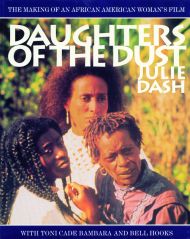

Toni Cade was at the forefront of that re-visioning. She collaborated with Louis Massiah to create the documentary Bombing Of Osage Avenue and W.E.B. DuBois: A Biography in Four Parts. She worked with John Akomfrah as the narrator for Seven Songs of Malcolm X. She wrote the lead essay for the book introducing Julie Dash’s epic film Daughters of the Dust. She mentored bell hooks and Terry McMillan, women who would critique cinema culture and upend it through their books. I do not know all of the names of the many writers, educators, filmmakers, and activists that she inspired around the world from Philadelphia to Mexico City to London to Cairo or to Tokyo, but they are legion.

Toni Cade was at the forefront of that re-visioning. She collaborated with Louis Massiah to create the documentary Bombing Of Osage Avenue and W.E.B. DuBois: A Biography in Four Parts. She worked with John Akomfrah as the narrator for Seven Songs of Malcolm X. She wrote the lead essay for the book introducing Julie Dash’s epic film Daughters of the Dust. She mentored bell hooks and Terry McMillan, women who would critique cinema culture and upend it through their books. I do not know all of the names of the many writers, educators, filmmakers, and activists that she inspired around the world from Philadelphia to Mexico City to London to Cairo or to Tokyo, but they are legion.

When we (my mother, Marlene Patterson, and I) were working on Moving with the Dreaming, a documentary about Aboriginal modern dance in Australia, we knew we did not want it to look or feel like your typical documentary with the voice of God narration and archival footage. We wanted to use dance to tell the story. We had a half hour to reveal the 60,000-year history of Aboriginal people in Australia, their civil rights struggle, and the importance of art and culture in their struggle to be recognized as human beings. How do you collapse all of that into one film? We had to think in Dreamtime (the non-linear realm of creation in Aboriginal cosmology). At Toni Cade’s suggestion, we used the skeleton of the mythic five-part epic hero journey as the foundation for the documentary. By studying Aboriginal mythology, we discovered the importance of rock paintings and used that imagery to inform the film.

Toni Cade told us to examine the films of Maya Deren. Deren is one of the first experimental filmmakers in the U.S. and the best, in my opinion, in terms of dance films. Hers was a truly American cinema in that it includes the female point of view, and has a very cross-cultural dynamic. She captured time and motion in film in a non-linear way. Her conception of time and space helped me to understand the elasticity of film as a medium. Like Toni Cade, Maya Deren’s creative work exists outside of convention. This elastic quality of film-time helped us to construct the Australian documentary in a way that operated on multiple levels. The images showed the ancient aspects of the Aboriginal culture, the commonalities with the Black Power Movement in the United States, and the cross-cultural fusion in dance.

I wish more filmmakers could be exposed to the teachings of Toni Cade Bambara. Her short stories, novels, and essays help to open up one’s mind’s eye to a new way of seeing. She was voracious in her appetite for films. She remembered every film that she saw, and could apply the plotline, performance, shot or film score to any topic in class. Talking with her made you think that you could actually make a film, and make a good one. She would often ask, “What are you working on now?” followed by “What’s your plan?” She made the arduous task of creating a film seem possible, one step at a time. No doubt.

Nadine Patterson, along with her mother Marlene Patterson, operates the film production and consulting company Harmony Image Productions in Philadelphia. They have been producing award-winning independent films together for over 20 years. Toni Cade Bambara inspired them both in workshops at Scribe Video Center and helped to shape their first documentaries Anna Russell Jones: Praisesong for a Poineering Spirit and Moving with the Dreaming, serving as narrator for the former. Their current film Tango Macbeth is a re-visioning of Shakespeare’s work through an Afro-centric and multicultural lens. For more information, visit www.hipcinema.net and www.tangomacbeth.com. You can also follow Nadine on Twitter @hipcinema.

Nadine Patterson, along with her mother Marlene Patterson, operates the film production and consulting company Harmony Image Productions in Philadelphia. They have been producing award-winning independent films together for over 20 years. Toni Cade Bambara inspired them both in workshops at Scribe Video Center and helped to shape their first documentaries Anna Russell Jones: Praisesong for a Poineering Spirit and Moving with the Dreaming, serving as narrator for the former. Their current film Tango Macbeth is a re-visioning of Shakespeare’s work through an Afro-centric and multicultural lens. For more information, visit www.hipcinema.net and www.tangomacbeth.com. You can also follow Nadine on Twitter @hipcinema.

You may also like...

3 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Image Weavers: In Honor of the Spirit of Toni Cade Bambara - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Feminists We Love: Linda Janet Holmes [VIDEO] - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire